CSU may up their college admissions requirements. But will that hurt low-income students?

- Share via

As a high school freshman, Jennifer Velasquez worked every day after classes helping her mom sell elotes, raspados and tacos from a street cart in East Los Angeles. With rent to pay and siblings to support, they would often work late into the night, sometimes until 2 a.m. — and she would get only a few hours of sleep.

It’s why, in part, she failed Algebra I.

She repeated the class her sophomore year, and then moved on junior and senior years to Geometry and Algebra II, determined to meet the requirements for admission to the Cal State University system. She was accepted to Cal State Los Angeles, and, last month, Velasquez, 19, became the first in her family to attend college.

“It was difficult,” Velasquez said. “If I had to do four years of math, it would have been more difficult.”

Velasquez is among the students, parents, educators and Los Angeles school board members who are opposed to a proposal by Cal State University to require a fourth year of math, science or other quantitative high school coursework for admission, laying bare a tension between two imperatives in California education.

On the one hand, Cal State is seeking to raise standards and academic preparation for all high school students, especially in math. Yet this objective has become mired in a debate about disparities in educational access and quality that disproportionately harm high school students of color and those from low-income families in the state. Some fear that these students’ access to Cal State will diminish if the proposal is adopted.

“Black and Latinx students and low-income students can and do achieve at high levels,” said Elisha Smith Arrillaga, executive director of Education Trust-West, a nonprofit group focused on educational equity, at a recent hearing on the proposal. “But when we look at other facts, at data on access and on opportunity, it becomes clear that these students are also given barriers by our education system that limit their access to the teachers and to the courses that they need to attend college.”

The Cal State proposal would require incoming freshmen, beginning in 2026, to have taken four years of quantitative reasoning, which the university defines as “the ability to think and reason intelligently about measurement in the real world.” The board is scheduled to hear a formal proposal later this month and could vote on it as soon as November.

The requirement could be met by an additional year of math or science, an elective with quantitative content such as statistics or computer science, or some career and technical education courses. An exemption would be allowed for students who cannot meet the requirement because their school doesn’t offer a qualifying course.

CSU seeks to improve student success

James Minor, assistant vice chancellor, noted this isn’t the first time that controversial policies that try to improve student success and close equity gaps have been proposed. He cited the development of the “A-G” requirements, a sequence of 15 college-prep courses required for admission to the Cal States and UCs. More recently, Cal State decided to do away with non-credit remedial classes, after finding that they cost students more money and time, without being particularly effective.

“We think, by systematically raising the bar, we’re asking all of our students, regardless of what school district they go to, regardless of what neighborhood they live in, to arrive with more similar levels of preparation,” Minor said.

He also said that racial disparities in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) fields can be traced directly back to high school, and the proposed requirement would help lessen those.

Cal State data show that students who enter their first year of college having taken an additional quantitative reasoning course are more likely to complete their general education math requirement, return for their second year and graduate. The data do not show a causal link, but Minor said the correlations are strong enough, across ethnic and income groups and over time, to guide policy making.

Overall, research shows that academic preparation in high school, including in math, is the strongest predictor of college success, said Michal Kurlaender, a professor of education at UC Davis who researches educational pathways and access to college.

But it can be difficult to parse out how much of that success is a result of purely academic achievement, or of a host of other factors that enabled students’ preparation, such as a better school or home environment or stronger teachers.

Disparities among black and Latinx students

Kurlaender said there is some evidence that when higher standards are put in place, schools can and do rise to the occasion. She said, however, there can also be unintended consequences in a statewide K-12 system, in which there are deep disparities in college readiness.

“The implications of a policy like this will not be evenly felt,” Kurlaender said. “They will be disproportionately targeting students who are less likely to be found in this pathway already.”

Those are Latinx students, African American students, low-income students and students who attend schools where seniors don’t currently take math, according to a paper Kurlaender and her colleagues published last week.

Critics of the proposal argue that such findings are precisely the reason to reject such a requirement or, at least, slow down before adopting it.

Arrillaga, of Education Trust-West, pointed to state data showing that 8 out of 10 black and Latinx students in California do not meet math standards.

“For us to add a whole extra requirement that specifically focuses on math and quantitative reasoning ... means that there really needs to be a deep and serious plan in place,” Arrillaga said.

She said that plan should include identification of the districts that would be most impacted, a strategy for directing high-quality teachers to those schools, and metrics for evaluating progress in increasing course offerings at underresourced schools.

Across the region and state, educators are divided on the proposal.

How one school added more math classes

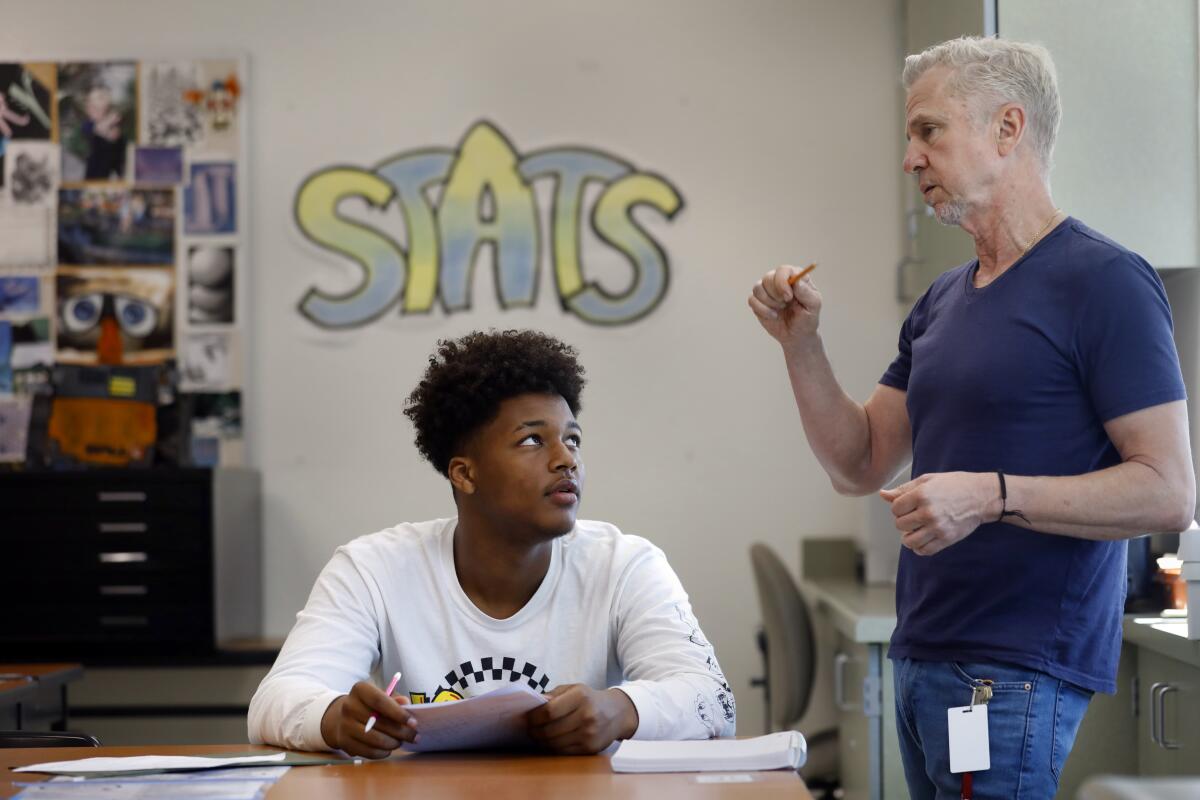

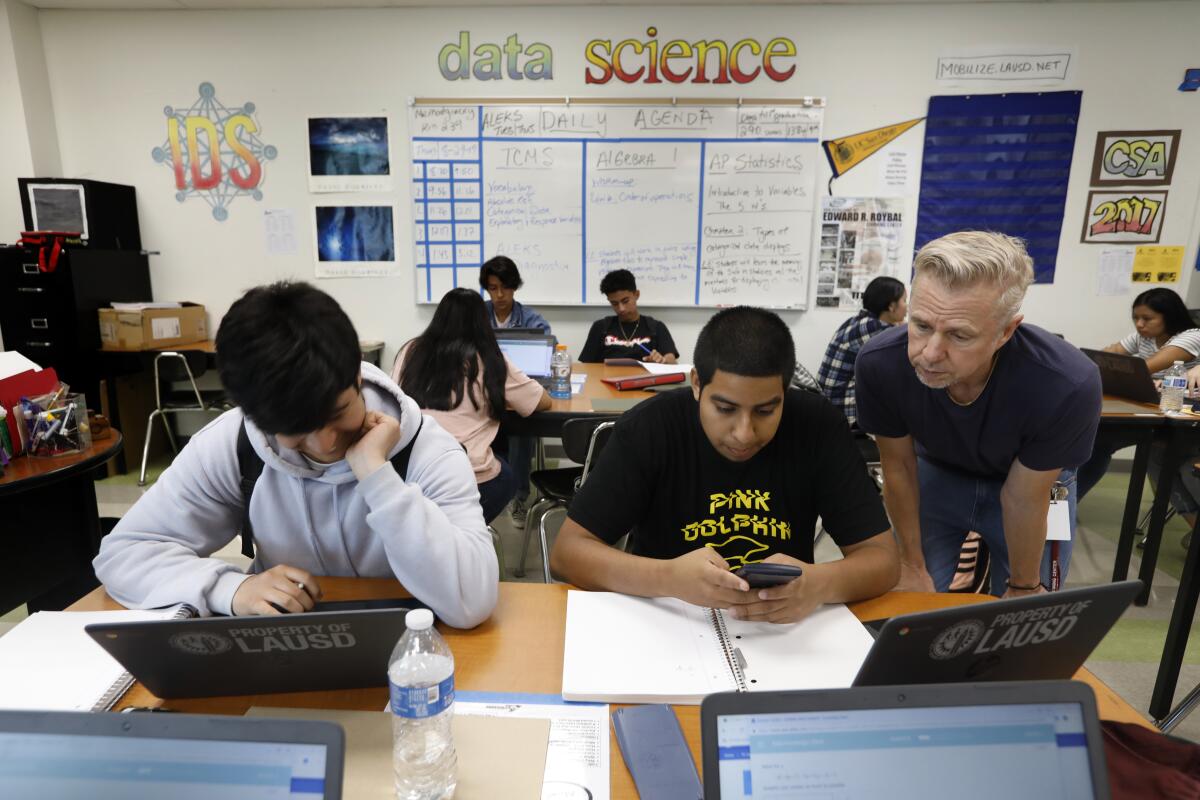

At Roybal Learning Center downtown, Robert Montgomery teaches “Transition to College Mathematics and Statistics,” a course developed by the Los Angeles Unified School District in partnership with Cal State Northridge as an alternative math class for 12th graders. The course includes review of essential math skills and hands-on, group-based problem solving.

One recent morning, Montgomery walked his 23 students through a lesson on comparing risk. He put up a table on the slide projector that showed the frequency of lung cancer among smokers and non-smokers and asked his students, working in groups, to answer a series of questions about the data.

“You just need some very simple math … It all has to do with that data table,” he told them.

Montgomery, who has taught math for 30 years, has long been a proponent of a fourth year of high school math. But, he said, “I got tired of the kids asking, ‘Are we ever going to use this?’ ”

One of his students, Kenia Zelaya, struggled in Algebra I, Geometry and, especially, Algebra II honors, in which she said she received a D grade.

“I used to love math, but when I got to high school I thought math was so hard,” the 17-year-old said.

That day in Montgomery’s class, though, Zelaya was the first to solve a math riddle involving a group of people crossing a bridge under a particular set of constraints.

“This is one of my favorites classes to come to,” she said.

Montgomery said that making a fourth year of math a requirement would not be a burden at his school, where the vast majority of students are Latinx and low-income.

Teacher recruitment would be hard

Cynthia Gonzalez, principal of the communications and technology high school at the Diego Rivera Learning Complex, where the vast majority of students are also Latinx and low-income, agreed the intent behind the proposal is a good one.

But, she said, the requirement is “not going to trigger resources to our schools.” Paying a hard-to-recruit math teacher would be difficult, she said.

“The reality in communities like ours is that ... unless there’s a larger initiative by the district to make sure our schools have priority placement or heavy recruitment … it might not ultimately meet their intended consequences,” she said.

The Los Angeles school board opposes the Cal State proposal, writing in a motion this summer that the requirement would further exacerbate access barriers for students of color and low-income students, who make up the majority of the district. The district currently only requires three years of high school math to graduate. Leaders in the Anaheim, Sacramento and San Francisco public school districts have also opposed the proposal.

Los Angeles board member Jackie Goldberg said that it would be fine to require the additional year of math for students who intend to major in a math-heavy field. But a universal requirement would deny access to students who “really should be there and will do well there,” she said.

Board member Monica Garcia expressed concern that the policy change was an effort by Cal State to contain enrollment.

Long Beach school experiment shows promise

Cal State officials say they remain committed to ensuring equitable access and that the proposal is by no means an effort to curb enrollment. They note that more than 90% of students already meet the proposed requirement. They also point out that Cal State turns out the majority of the state’s teachers and has recently committed $10 million to train a new crop of math and science teachers.

In Long Beach Unified School District, an experiment to require more math is already underway.

Six years ago, Long Beach Unified Supt. Christopher Steinhauser, who is also a member of the Cal State Board of Trustees, met with the presidents of Cal State Long Beach and Long Beach City College to discuss adding a fourth year of math in high school, since so many graduates went on to need remedial coursework in college.

Long Beach schools, where the majority of students are non-white and come from households below the federal poverty level, phased in the graduation requirement over four years. Over that time period, the district’s graduation rate went up, as did the percent of students meeting the A-G requirements and becoming eligible for Cal State admission.

“When you raise the bar and you provide the right support for everybody — for kids, for teachers, for parents — kids meet that standard and exceed it,” Steinhauser said.

Times staff writer Howard Blume contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.