Charter school compromise could intensify L.A.’s school board battles

- Share via

A major agreement aimed at setting stronger standards for charter schools stands to intensify power struggles for seats on the Board of Education in Los Angeles, setting the stage for more contentious and costly election battles between charter advocates and allies of the teachers union, a cross section of education leaders and experts said.

Under a compromise announced last week by Gov. Gavin Newsom, local school boards will have more authority to reject new charter school petitions, making their decisions crucial to the growth of the charter sector. The proposed law, which still needs legislative approval, also requires charter school teachers to hold the same credentials as those in traditional schools and attempts to increase accountability for charters — moves touted as better serving students.

For the record:

4:24 p.m. Sept. 3, 2019A previous version of this article said that $15 million was spent in the 2017 race in which charter-school-backed Nick Melvoin defeated teachers-union-backed school board president Steve Zimmer. Spending in the race was nearly $10 million.

In Los Angeles, school board elections already were the most expensive in the country — as the influential teachers union went head-to-head against better funded pro-charter school groups seeking a controlling majority on the seven-member body. A record breaking $17 million was spent on three 2017 board races, including nearly $10 million in District 4, where charter-backed Nick Melvoin defeated union-backed school board president Steve Zimmer.

While the compromise may calm some contention at the state level, in Los Angeles “there are folks on both sides who are going to be even more crazy on local school board elections,” Melvoin said.

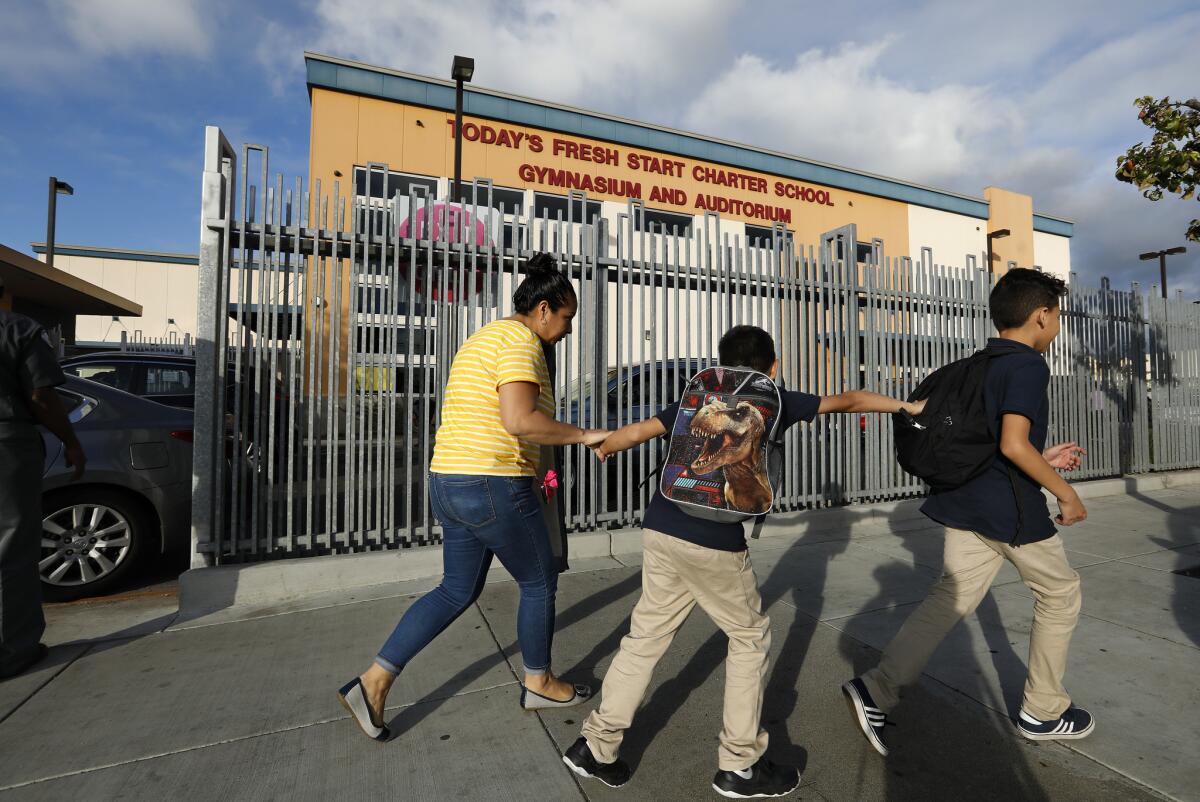

The stakes are especially high in Los Angeles, where close to 20% of public school students attend 224 charters, more than any other school system in the nation. Currently, the board is closely divided on many issues affecting charters, but leans toward tighter restrictions.

Union-backed board member Jackie Goldberg will be on the 2020 ballot. She won a special election to finish the term of a charter-backed board member who resigned after pleading guilty to breaking campaign finance laws.

“I think the charter folks identified that my election ended their four-vote majority and they’re going to try everything they can to get it back and then some,” Goldberg said. “Now they’re going to say if they don’t get it back, by God, there won’t be any new charters in L.A. Unified. That’s not true, but that’s what they’ll say.”

Both Melvoin and Goldberg generally support the compromise that was worked out, despite the ramifications for local elections.

“This will make school board races even more important,” said political consultant Eric Hacopian, who has worked on behalf of candidates on each side of the divide.

Charters are privately operated public schools, typically run as nonprofits. Most are non-union. Statewide, about 10% of students are enrolled in more than 1,300 charter schools.

Supporters say charters offer families high quality, diverse schooling options and compel helpful competition. Critics say that charters can undermine district-run schools by siphoning off more motivated families and funding, leaving behind students that are more challenging and expensive to educate.

The agreement between the teachers unions and charter organizations announced by Newsom last week represents the biggest revision to state charter law since it was first enacted in 1992, when charters were widely viewed as a niche experiment to foster innovation.

They have since become a central education reform strategy, often with wealthy backers and foundations propelling their growth. In Sacramento, there’s been a decades-long stalemate over charter regulations, with lobbyists for charters and unions frequently fighting to a draw, preventing even commonsense updates.

As one example, the evaluation for renewing a charter every five years is supposed to rely on scores from the standardized STAR test and a school’s resulting rating on the state Academic Performance Index. Neither the STAR tests nor the API ratings have been in use for several years. The agreement fixes that, relying on the state’s new performance metrics for all public schools. These include updated testing systems and factors such as attendance, suspensions and graduation rates.

And the 1992 law made no provision allowing a school district to close a charter for financial corruption. Instead, officials had to assert instead that the charter was “unlikely to successfully implement the program set forth in the petition.”

The current compromise was hammered out with help from Newsom and state Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond. Both were elected despite the big-money efforts of charter school backers to defeat them. As they played a central role in shaping the agreement, they said they simply wanted a helpful course correction.

The California Charter Schools Assn. announced it was “neutral” on the proposed legislation after opposing earlier versions.

“Collective action of the charter schools sector ensured CCSA was able to secure significant protections for charter school students and schools,” the association said in a statement.

Another group, Charter Schools Development Center, announced it’s against the deal: “What has been shared indicates that the proposal is substantively similar to, and in key respects more punitive,” than an earlier version of the legislation that the center also opposed.

Leaders of teachers unions have been generally enthusiastic.

“This [is] a great first step in the ongoing, multi-year effort to fix California’s broken charter laws,” said Alex Caputo-Pearl, president of United Teachers Los Angeles in a statement. The bill “is the result of collective action and organized collaboration between educators, parents and our communities throughout California.”

The push for revisions to the state’s charter law was accelerated by recent charter scandals and investigative reporting, including by The Times. Teachers’ strikes in L.A. and Oakland also fueled the momentum.

The final version of the new rules will appear in a revised version of Assembly Bill 1505, authored by Assemblyman Patrick O’Donnell (D-Long Beach), a former high school teacher.

The new discretion for rejecting future charters allows boards take into account the impact on district finances. Previously, a district had few legal options for rejecting a charter, although some districts did so anyway.

“If fiscal threat is one of the criteria for denying charter petitions, it is not hard to foresee the board denying all new charter petitions,” said Charles Kerchner, senior research fellow at Claremont Graduate University’s School of Educational Studies.

Unions and many district officials badly wanted the financial impact test, but it has limitations. For example, it can be invoked if a district is on the verge of insolvency or if a district could be pushed into deficit spending by a new charter. In L.A., neither scenario seems likely.

But other considerations also would come into play in board decisions. District officials could consider whether the charter would undermine or duplicate a program already offered in that area.

For their part, charter advocates are pleased with a provision requiring school boards to determine whether a charter will serve academic needs not being met by a local school with low test scores.

“You want to provide folks closest to ground with discretion,” said one person close to the negotiations but not authorized to be quoted by name. “If this were super prescriptive that would be an abridgment of a local community’s perspective. ...Chartering authorities must consider whether academic needs trump fiscal impact.”

One possible outcome of interpretive wiggle room is litigation. When the state required districts to share classrooms with charters, for example, years of lawsuits ensued in Los Angeles over what qualified as available space and the meaning of the words “reasonably equivalent.”

If a board rejects a charter application, the decision can be appealed to county boards of education.

“This seems like a feel-good bill for the teachers union but charters can still do what they want and still get approved if the county Board of Education is an option,” said pro-charter political strategist Mike Trujillo.

Melvoin said charters could take heart in the potential for existing, high-performing charters to have longer operating agreements and a more streamlined process for getting them approved. Under existing law, all charters must go through a lengthy renewal process every five years.

One potential charter concern, Melvoin said, is a provision requiring all instructors to obtain formal teaching credentials. Up till now, some charters have made creative use of industry professionals, including dancers, musicians and scientists, who are available to teach a few classes but don’t want to pursue careers as full-time teachers.

Melvoin said it would have made more sense to go the other way and provide for traditional schools to have similar hiring flexibility in special cases.

Union leaders, however, have been reluctant to open the door to teachers working outside the traditional certification process.

Goldberg would like additional accountability measures, including open meetings by the senior boards of charter management groups and greater financial disclosure. She would have supported a broader moratorium on new charters, because, she said, “we still have a lot to figure out.”

Taryn Luna contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.