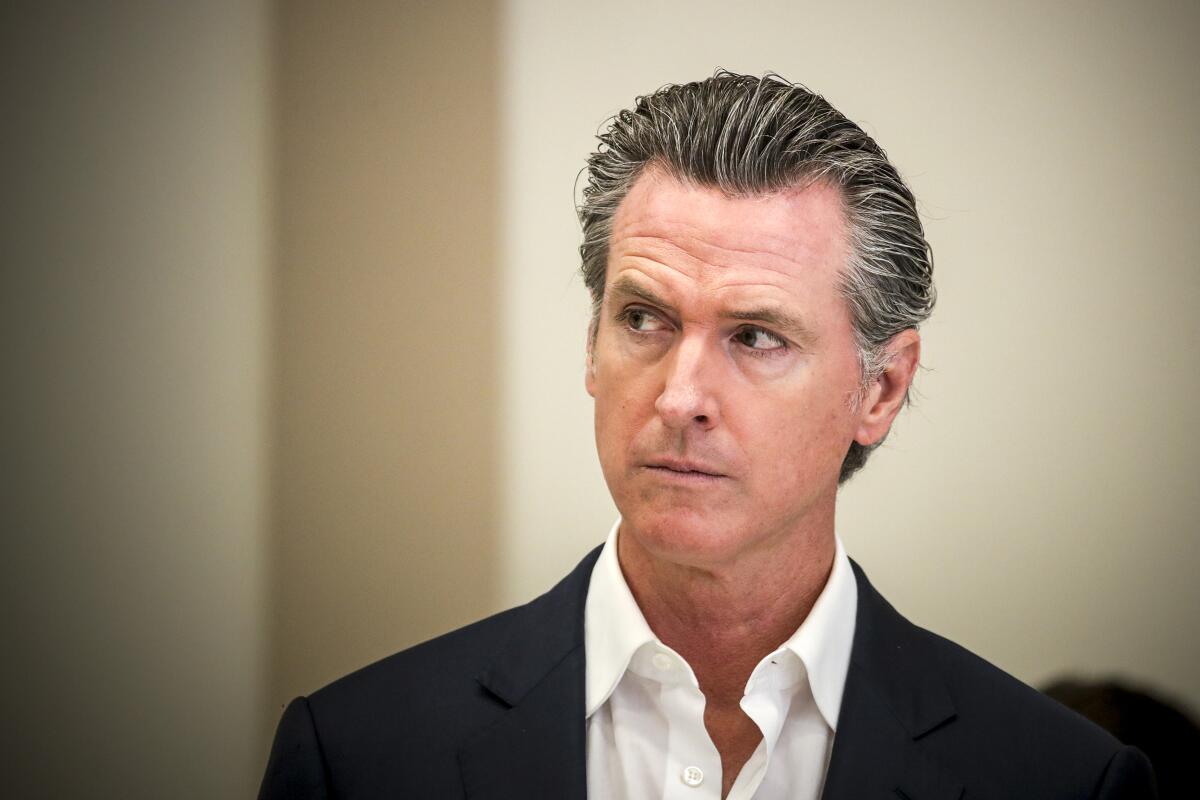

California Politics: The Newsom recall election is underway

- Share via

Twenty-two million ballots. Forty-six candidates. Two questions for voters. One career-defining moment for Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Everything that’s happened so far in California’s historic recall election has been prologue. Now is when the campaign really begins, as Newsom’s opponents and supporters launch statewide get-out-the-vote efforts and elections officials mail ballots to every registered voter in the state.

Momentum will matter. But so will the election’s mechanics — a recall is a unique experience for voters, and substantial questions remain about how much Californians understand the process and what may (or may not) be legal.

And the politics of the gubernatorial recall are on a collision course with the final month of work for the California Legislature. Major policy battles are looming in the state Capitol, issues that could become entangled in Newsom’s electoral reckoning. Democratic lawmakers may feel pressure to sideline some of their progressive bills in hopes of shielding the governor from any blowback. Or they may choose to unveil new, feel-good policies to boost his standing.

Both storylines will reach their boiling point at the same time. Legislators will take their final votes and adjourn on Sept. 10, four days before election day.

It might be the perfect time for the launch of this new weekly newsletter.

Welcome aboard and buckle up

Welcome to the inaugural edition of California Politics, a newsletter from The Times chronicling the people and policies that govern the Golden State.

It’s been almost six years since I began filing weekly dispatches from Sacramento as part of our Essential Politics newsletter. Consider this a close cousin, a new effort to provide clarity and context for political happenings in the state. And let me remind you that you can sign up for the twice-weekly newsletter written by my colleagues in Washington.

The California Politics newsletter will undoubtedly be a work in progress, and we’re eager for your feedback. Now, let’s get to it.

Recall ballots: Who votes and when

For only the second time in California history (the first being last November), every registered voter is about to receive a ballot in the mail — more than 22 million ballots in all, a number roughly equal to the total number of voters in 20 states.

Holding an election over an entire month changes the traditional political calculus. Voters who cast ballots in late August, for example, may judge Newsom and the 46 recall replacement candidates differently than those who vote after Labor Day.

But the biggest question in this recall election centers on who will vote.

Let’s begin with a snapshot of California’s registered electorate: Almost 10.3 million voters are Democrats, followed by about 5.3 million Republicans, 5.1 million independent voters and almost 1.4 million voters who are registered with one of the state’s other officially recognized parties.

Two other data points: Almost 1.5 million voters signed the Newsom recall petition, and roughly 30% of California’s independent voters typically lean toward the GOP.

Last month’s poll by UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies and co-sponsored by the Los Angeles Times found 54% of registered voters were “very interested” in casting a recall ballot. Using state registration data, that’s the equivalent of roughly 11.9 million voters who are a sure thing to cast a ballot.

(Some context: California’s average turnout in November elections since 2010 is 65.7%, a number skewed a bit by last November’s record turnout. The average turnout in statewide primaries over the decade was 36.9%. Turnout in the 2003 recall of then-Gov. Gray Davis was 61%.)

But here’s where enthusiasm is a potential game-changer. The Berkeley/Times survey found 78% of registered Republicans said they were “very interested” in voting in the recall, a level of engagement shared by only 47% of registered Democrats. That asymmetry could obliterate the traditional advantage of Democrats — should the poll’s findings hold up, the Democratic Party’s built-in advantage could shrink to fewer than 650,000 votes.

Because that doesn’t take into account Democratic-leaning independent voters, Newsom’s buffer is probably bigger. But it helps explain the poll’s finding that, among likely voters, the race was neck and neck as of late July. It’s also why, absent some blockbuster developments, the recall election’s outcome is likely to hinge on Democratic voter apathy.

“Is there anything we can say to convince you that your donation before ballots drop is absolutely critical to our ability to beat this recall?” a Newsom fundraising email this week asked donors. “What about the fact that far-right Republicans are motivated to vote and Democrats hardly know there’s an election?”

On Thursday, President Biden weighed in. “He knows how to get the job done because he’s been doing it,” Biden said about Newsom in a prepared statement.

The governor launched his anti-recall effort several weeks ago with broad swipes at Trump supporters and the GOP, a line of attack that a judge ruled Newsom could use in the voter information guide. But in recent days, he’s zeroed in on one Republican in particular.

Elder’s entry shakes up the race

One of the last candidates to join the recall ballot is now commanding a sizable amount of attention. Larry Elder, a longtime Southern California talk radio host, has been able to quickly capitalize on his social media following and almost daily appearances on national conservative TV talk shows.

My colleagues James Rainey and Seema Mehta took a look this week at Elder’s long career of offering opinions on a variety of topics. They also pointed out his early success at fundraising. (It was a Bakersfield fundraiser that Elder said kept him from participating in a debate last week with other GOP hopefuls.)

“One of the first rules of politics is to show up,” wrote columnist George Skelton. “And to win a competitive contest, you’ve got to compete — including in debates.”

(Speaking of money: It’s important to note that neither Elder nor any Republican candidate has come close to the campaign cash stockpiled by Newsom.)

No Republican recommendation

Elder’s early momentum — the Berkeley/Times poll found him leading the pack of replacement candidates with the support of 18% of likely voters — may explain the California Republican Party’s decision not to endorse a GOP candidate in the recall election.

The endorsement could have been a boost to Kevin Faulconer, the former San Diego mayor whose candidacy has long seemed built on the idea that he is the Republican best poised to end the party’s 15-year drought in winning a statewide election. Faulconer certainly seemed during the Aug. 4 debate to be trying to balance a centrist stance on some issues with the conservative demands of Republican voters.

During the debate, former Rep. Doug Ose perhaps landed the event’s best quote when he said solving the problems at the state’s beleaguered unemployment department starts with something simple: “Just answer the damn phone. All right? Just answer the damn phone.”

The other two leading GOP candidates — businessman John Cox and Assemblyman Kevin Kiley — have been issuing a flurry of policy proposals since last week’s debate. Cox promised a 25% income tax cut for every Californian if elected (which would mean a huge tax break for the most wealthy); Kiley demanded new transparency and accountability at the state Public Utilities Commission.

Answer both recall questions?

Earlier this week, we wrote about the lingering confusion for some voters on how the recall ballot works — some don’t realize that the choice they make on the first question (whether to recall Newsom from office) doesn’t affect their right to vote on the second question (if he’s removed, who will replace him). Voters can vote to keep Newsom in office but also choose a replacement in the event he’s ousted.

Democratic Party leaders are urging voters to simply skip the second question. Some readers scoffed at the idea that Newsom and his supporters have any responsibility to educate voters about their right to choose a replacement candidate, rightly noting that the party chose an all-or-nothing strategy to back only Newsom and urge other prominent Democrats to sit out the race.

In his Thursday column in The Times, Skelton wrote that voters should reject Newsom’s advice.

His point is one expressed by a number of voters: What happens if Newsom is recalled and the top replacement candidate becomes governor-elect with a fraction of the votes Newsom won on the first question? It’s a scenario that UC Berkeley School of Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky and professor Aaron S. Edlin, writing in the New York Times this week, believe would be unconstitutional.

There’s another wrinkle to consider, as I wrote about in a Twitter thread this week: Does the California Constitution suggest the office of governor, when vacated by a recall election, should be filled by the lieutenant governor? It’s a possibility under an amendment made in 1974 that says a replacement election should be held “if appropriate.”

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

This week’s redistricting prelude

Thursday marked an important milestone in the process to draw new state and local political maps in California, as the U.S. Census Bureau released the long-delayed 2020 population data on which map drawers will rely to craft new local, legislative and congressional districts.

The data reveal the changing identity of the state and the nation. California now ranks second of all states in diversity (behind Hawaii) with a plurality of its residents — 39.4% — identifying as Hispanic or Latino. One other fascinating snapshot: using the Census Bureau’s “diversity index,” which measures the likelihood that two people chosen at random will differ in their race or ethnicity, the most diverse area in California is Solano County. Los Angeles County ranked 13th on the diversity index; the least diverse county, per the census analysis, is Imperial County, where 85.2% of residents identified as Hispanic or Latino.

With the census results now in hand, look for the initial redistricting data — which incorporate California voting information — to be released Aug. 19. From there, it will take 30 more days to adjust the population numbers to account for state prison inmates, under a California law requiring prisoners to be counted in redistricting in the communities where they last lived before being incarcerated. California’s citizens redistricting commission still expects to begin its line-drawing in early October.

As I wrote in the Essential Politics newsletter last month, we still don’t know how long the state panel will have to complete its work. Commissioners want the California Supreme Court to extend the deadline to Jan. 14, though they have yet to formally petition the court. Some local redistricting commissions want the Legislature to give them the same deadline as the state commission.

California politics lightning round

— California’s Supreme Court decided Wednesday to let stand a ruling that said Newsom’s emergency powers during the pandemic include the right to alter or make new laws.

— Newsom has allowed the release of a man who served four decades in prison for the murder of a developmentally disabled California man who was buried alive.

— U.S. citizenship will no longer be a requirement for many Los Angeles County government jobs.

— Is California’s “Hydrogen Highway” a road to nowhere?

— Pete Schabarum, the famously combative, influential Los Angeles County supervisor whose successful state term-limits ballot drive more than two decades ago dramatically altered California government, has died at age 92.

Stay in touch

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get California Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to [email protected].

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.