Uber blocks transgender drivers from signing up: ‘They didn’t believe me’

- Share via

Adrian Escobedo signed up to drive for Uber Eats to help support his family after his fiancee lost her job. The couple and their 4-year-old son had just moved to Bakersfield. Money was tight.

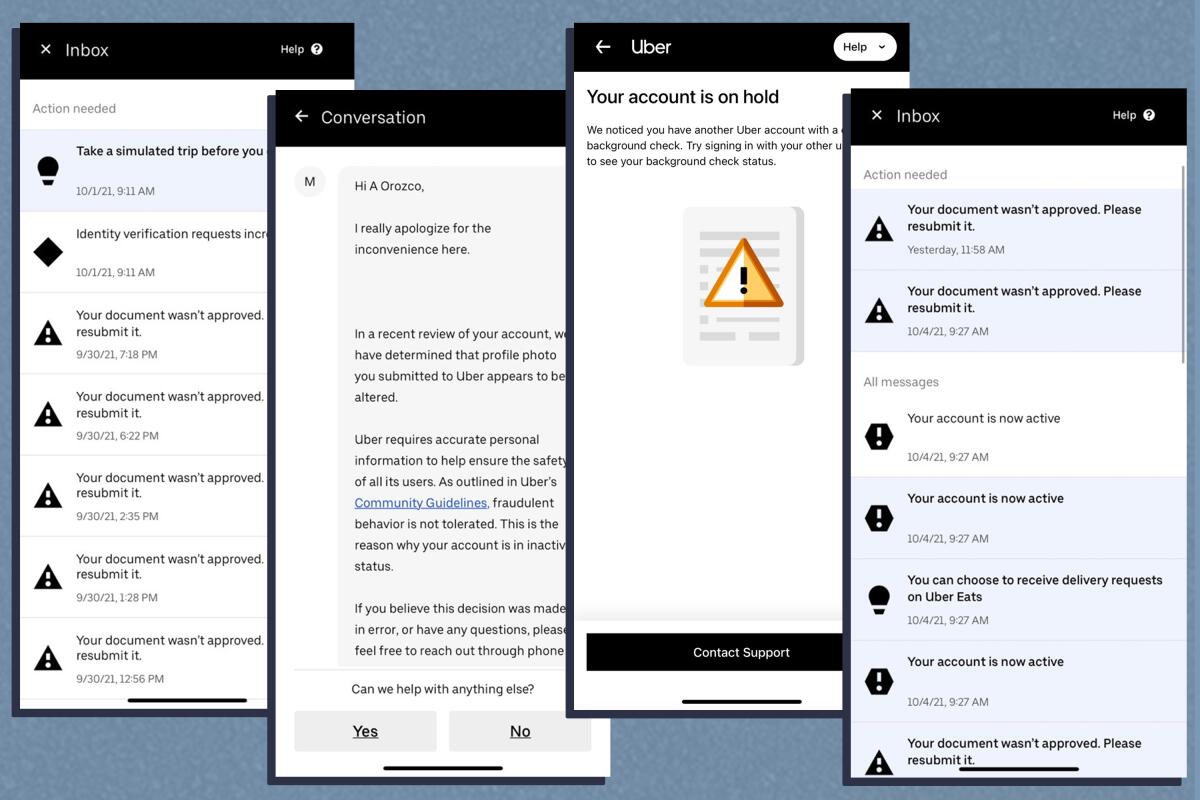

But after a lunch break on his first day, Escobedo found himself locked out of the app; his documentation had not been approved. Escobedo tried at least 20 times to resubmit the records, which included a photo of his face, copies of his ID and proof of car insurance, he said. Each time, they were denied.

“I was very confused as to what was wrong,” Escobedo said. “I thought I was being messed with.”

Then, looking over his documents, Escobedo figured it out: He is a transgender man, and his appearance in his older driver’s license photo does not match the current photos he submitted, showing his wispy mustache and goatee.

Uber at times has blocked transgender and nonbinary people from driver and delivery jobs by treating their documents as fraudulent, suspending their accounts and failing to rectify the situation, according to interviews with drivers and documentation provided by the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, which petitioned the company to restore Escobedo’s account.

Drivers have had their accounts permanently banned, according to documentation of written communications with the company shared by five workers. None managed to get their accounts reactivated through Uber’s appeals process.

One driver had been working for Uber Eats for more than a year without issue. Prompted by the company’s marketing of a new option allowing transgender drivers to update their names and profile pictures, she resubmitted her documents in late August. Her profile photo was rejected as fraudulent, her account was shut down and she was permanently removed from the platform.

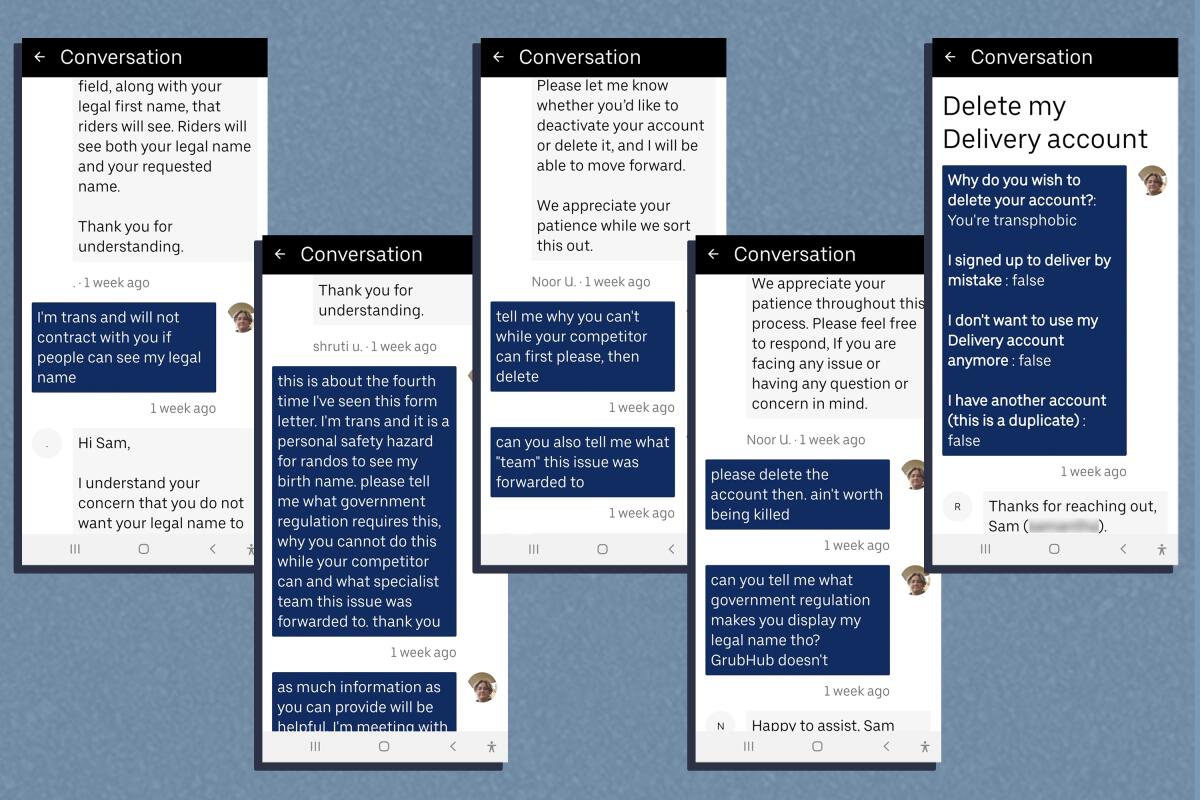

Blocked applicants said they spent hours messaging and calling the support desk, often to no end. Some haggled with Uber for days to get their true name displayed instead of their “deadname” from before they transitioned.

At a time when a worker shortage has emerged as a key problem for Uber, the company’s approach pushed all of these drivers to other app-based services, including Lyft and DoorDash, which for years have had policies accommodating name changes for transgender drivers.

The missteps have also undermined Uber’s stated commitment to more inclusive and equitable practices, and highlight the dearth of protections for independent contractors who face discrimination.

Uber spokesman Zahid Arab said that matching profile photos to government IDs is a fraud prevention measure the company undertakes as part of its safety protocols. Arab said in an email that “on occasion, requests can be misrouted and result in a regrettable customer experience which we are working to address.”

“Uber and our partners make every effort to remedy situations like this in a timely manner,” Arab said. “We continue to work on improving internal processes and working with our third party background check providers to help ensure the background check process runs as expected for transgender and nonbinary users.”

Uber is working to reactivate accounts The Times inquired about, Arab said Thursday afternoon. “We’ve worked to train Uber staff to handle all requests with compassion, empathy, and respect. We regret the confusion and pain that is caused when we don’t meet that standard,” he said in an emailed statement.

Pride month

On June 1, as part of its Pride month campaign, Uber announced plans “to create a safer, more inclusive company” for transgender, nonbinary and other LGBTQ+ identifying customers and drivers. The company said it would allow trans and nonbinary drivers to display their self-identified first name, and establish a $60,000 fund to help its drivers cover the costs of updating their legal IDs and records.

Days later, Escobedo’s account was suspended. He asked Uber’s support desk why it had rejected his documents. Escobedo explained that the profile picture he submitted was taken after he transitioned, whereas his driver’s license photo was from before. An Uber Eats representative said the issue was being escalated to a specialized team for review, which would take up to five business days.

More than a week passed. Escobedo contacted the support desk for an update; he got the same response, to wait five business days. Escobedo said the Uber representative told him the company had already contacted him about his case, but Escobedo told The Times he hadn’t received any communication.

In mid-June, he received an in-app message saying he had submitted fraudulent documentation and was banned from driving for Uber Eats. The deactivation decision was permanent, and he would not be allowed to appeal, the message read.

When Escobedo asked which documents were determined to be fraudulent, he received no response.

“They weren’t listening to me. They didn’t believe me,” Escobedo said.

The ACLU of Southern California sent Uber a letter July 1 demanding the company restore Escobedo’s profile and allow him to display his chosen name.

“As a result of having simply sought work using a current image that reflects his true, male identity, he was accused of fraud and permanently terminated from the platform, and suffered attendant economic and emotional harms,” the letter said. “Mr. Escobedo’s termination was an affront to his dignity as well as a likely violation of applicable law.”

The letter also urged Uber to review its records to identify any other prospective drivers or delivery workers “who may have been unfairly excluded from working for the company due to gender-mismatched documentation, and affirmatively communicate with those individuals about restoring them to good standing” by the end of 2021.

Adam Blinick, Uber’s senior director of public policy and communications, responded to the letter July 2, saying that the company would apologize to Escobedo and that it was “undertaking a review” of the issue and would “proactively address” any instances of similar problems the review uncovered.

That same day, the company reactivated Escobedo’s account.

Uber did not respond to emailed questions from The Times about whether it had conducted the review, what it concluded and any corrective actions taken.

A Kansas chapter of the ACLU had sent a similar letter to Uber Eats on behalf of a 41-year-old transgender man in Topeka contending the company’s app effectively outed him as transgender to customers by requiring him to display his legal name, which he said subjected him to harassment and ridicule, made him fearful for his safety and resulted in lower tips and fewer rides.

Hours later, Uber issued an apology and reaffirmed its commitment to making improvements to transgender drivers’ user experience.

‘Express your authentic self’

As part of its Pride initiative, Uber created a page on its website labeled “I am transgender and need account help.” On the page, the company advertised a form allowing drivers to update names or profile photos, to “express your authentic self,” and offered assurance that “a dedicated set of agents” would be ready to handle the request.

So far, Uber has handled some 1,800 requests to change names or profile photos, Arab said, and about a thousand support staff workers have received training in partnership with the National Center for Transgender Equality.

Monty Robinson, 22, based in Philadelphia, saw the new feature in August. Robinson transitioned after starting with Uber more than a year ago, and her photo was outdated. About a week after she submitted the form, the company deactivated her account and said in an Aug. 19 message that her new profile picture was altered or fraudulent.

Robinson works for DoorDash now. Her picture is still outdated. She said she is afraid to ask DoorDash to change it and risk termination from another delivery app.

Calvin Stephano, whose account was also deactivated when he tried to update his profile photo, said Uber’s appeals process doesn’t allow drivers to better understand or further dispute the company’s determination.

Uber initially flagged his photo as fraudulent, but in an Aug. 13 message, the company explained his termination by saying it “noticed a number of irregular trips associated with fraudulent activities.”

The charge made no sense to Stephano. He asked for an explanation in a phone call with a support representative, who told him he had already used up his one chance to appeal and she did not have the authority to override the system and recover his account, Stephano said.

“There was no way to get help. That’s when I thought, ‘This is really messed up,’” Stephano said.

The Uber support representative suggested he make a new account. Stephano didn’t bother trying.

Customer support limbo

Drivers described Uber’s support interface as a brick wall. Messages to the support desk would be elevated to a “specialized team” or were met with scripted responses that didn’t address specific questions or were entirely irrelevant. Review of appeals were said to take three to five business days, but drivers wouldn’t hear back for weeks. On phone calls, support desk staff were ill-equipped to answer questions or said they had resolved a problem, but the fix didn’t stick.

When drivers sought updates, they were assigned new service representatives who would start the process from scratch. After numerous exchanges, four drivers gave up, saying the process seemed futile.

Ajana Orozco, 54, a recent UCLA graduate, received contradictory instructions and explanations from the support desk.

Several service representatives told her to re-upload documents. Each time they were deemed fraudulent and denied.

Another said the account was on hold because it conflicted with Orozco’s existing passenger account.

Yet another representative told Orozco she was having problems because she kept uploading new photos.

“We went around in the same circle.... Here we go again: ‘Wait three to five business days,’” Orozco said. “It seemed like the more I kept calling them, the more they just put me to the back of the line.”

As part of Uber’s response to The Times, the company provided a statement from a woman who said she used to drive for Uber and lauded the company’s accommodations when she started her gender transition. When she explained why she needed a different name displayed, help desk staff were “so kind and changed it for me,” the former driver, Aimee Meredith, said.

But others say Uber’s support desk has made it harder for drivers to take appropriate safety measures.

Sam Moore, 27, of Santa Ana worried that having his legal name visible would out him as trans to customers and potentially put him in danger.

“Orange County is not the most progressive area,” Moore said. “Just being out and trans is enough, I don’t need to deliver that information along with the food when I go to people’s houses.”

But the company refused to display his chosen name. Instead, it kept Moore’s legal name and added “Sam” after it, in parentheses.

Moore furiously tweeted at the company, threatened to delete the app and mentioned he had a lawyer (his mother). Uber then fixed the issue and sent a link to information about its partnership with the National Center for Transgender Equality to help drivers fund name changes on legal records.

“They said, ‘Look how progressive we are’ after I had to fight with them for three days,” Moore said.

One of the drivers who got suspended from the platform because of a failed background check was advised by Uber support desk workers to contact Checkr, the third party service Uber uses to screen new drivers and conduct annual background checks. Uber spokesman Arab confirmed that drivers who temporarily lose access are asked to work with Checkr.

Uber’s website says that although the company relies on Checkr to screen drivers, Uber is ultimately responsible for the decision on a driver’s eligibility. “Checkr does not determine the standards used to evaluate eligibility to partner with Uber and is not involved in the partnership decision,” the website reads.

Lyft and DoorDash also contract with Checkr. It’s unclear whether similar breakdowns occur for transgender drivers working on other platforms.

Checkr did not respond to requests for comment.

Uber directed representatives from organizations advocating for LGBTQ+ civil rights that the company partners with or sponsors to reach out to The Times.

“There are some employers who take reactive measures, but we’ve seen Uber take a proactive approach to ensuring their platform is welcoming and inclusive that we think distinguishes them from other companies,” Samuel Garrett-Pate of Equality California, an organization sponsored by Uber, said in a phone interview.

Locked out

Transgender people face significant hurdles in the workplace. Deadnaming, misgendering and other offenses can trigger gender dysphoria and spur mental health crises. Some opt for self-employment or work in the gig economy, hoping a less formal setup will reduce their chances of experiencing discrimination.

Sometimes, it’s not a choice: Because they are visibly queer, trans people get locked out of employment opportunities at every stage, from resume screenings to interviews. In positions of serious vulnerability, trans people are more likely to take low-wage jobs and put up with harassment and discrimination, said Shannon Minter, legal director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights.

Independent contractors are often at an inherent disadvantage. Without traditional employee arrangements, they have less structural support, and they generally lack robust, if any, protection under discrimination laws, said Amanda Goad, director of the LGBTQ, Gender & Reproductive Justice Project at the ACLU of Southern California, who petitioned Uber to restore Escobedo’s account.

“If you’re doing gig work, you don’t get to have sustained relationships with colleagues and supervisors. You don’t have the normal ability to call HR with a question, and people trying to get support through an app get very mixed results,” Goad said.

In California, app-based drivers are governed by a different set of rules under Proposition 22, the 2020 voter-approved law bankrolled by Uber, Lyft and other gig companies that allowed them a carve-out from state law requiring the classification of some contractors as employees.

Goad said the measure’s passage took away strong protections gig workers might have had as employees under California law. For example, California law requires that employers comply with an employee’s request to be identified by a preferred name or gender pronoun, or else they could be held liable for discrimination.

Legal experts said Proposition 22 fails to delineate how discrimination claims by gig drivers would be processed and investigated, raising concerns that courts may not allow the cases to go forth.

Delivery driver Autumn Jean, a Tampa, Fla., resident, originally signed up to work as a delivery driver for Postmates. When the app was dismantled in June as part of Uber’s acquisition of the company the previous year, she tried to transfer to Uber Eats but was permanently deactivated in the process.

“The thing that was so frustrating was seeing [Uber] gallivant on Twitter about all the great things they’re doing for trans people,” Jean said. “Here I am, a trans person trying to make a living, telling you it’s actually impossible to sign up.”

The result, Jean said, whether the company’s actions are intentional or not, “has the effect of being transphobic.”