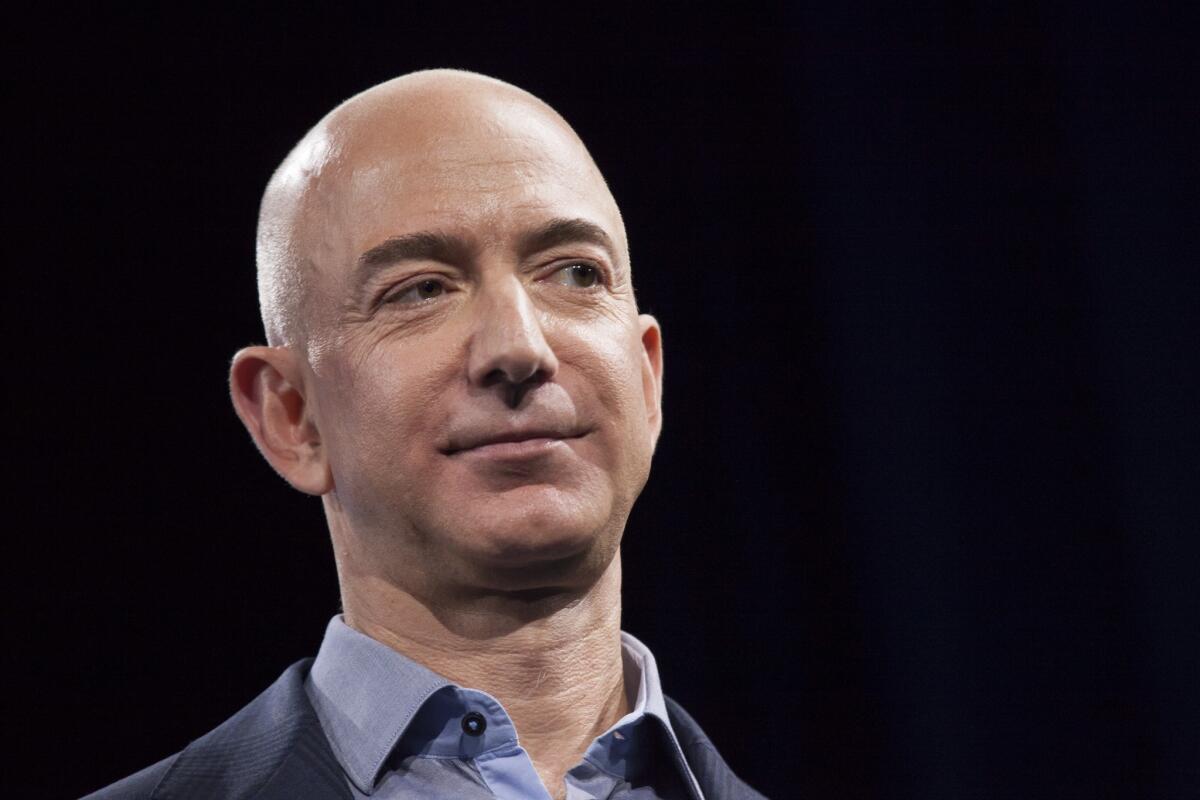

The spyware business is booming — just ask Jeff Bezos

- Share via

The alleged theft of data from the iPhone X used by billionaire Jeff Bezos has cast an unflattering light on the swiftly growing and highly secretive cottage industry of software developers specializing in digital surveillance.

NSO Group and Hacking Team are among the most well-known surveillance companies. Both have sold tools to law enforcement agencies that are used to covertly infect targeted mobile phones and computers with spyware, which can record calls, harvest text messages, take photographs using the device’s inbuilt camera and record audio using its microphone.

But many more companies, some of them not as well known to the public, are selling similar technology across the globe, as part of an industry that isn’t well understood and often subject to minimal regulation or oversight. The hack of Bezos’ phone has renewed calls from some officials for a moratorium on sales until more rigorous global controls are enacted.

“This industry seems to just keep growing,” said Eric Kind, director of AWO, a London-based data rights law firm and consulting agency. “Ten years ago, there were just a few companies. Now there are 20 or more, aggressively pitching their stuff at trade shows around the world.”

Spyware developers have maintained that they sell their technology to law enforcement and intelligence agencies to help catch criminals and terrorists. But as the surveillance trade has grown, it has been repeatedly criticized because its technology has been used to target activists, journalists and most recently, Bezos, the world’s richest person. Last week, it was revealed that the mobile phone of the Amazon.com Inc. chief executive was allegedly compromised by spyware sent to him from a WhatsApp account belonging to Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia. The Saudi Embassy denied the allegation.

While investigators haven’t identified the spyware that they suspect was used on Bezos’s iPhone, they cited NSO Group and Hacking Team as developing malware capable of such an attack. NSO has denied involvement, as has Memento Labs, which acquired the Hacking Team last year.

“Companies and governments make the argument that they need spyware tools in order to address counterterrorism and other kinds of violent crime,” David Kaye, the United Nations special rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression, said Thursday in an interview. “But the problem is you have no legal framework to ensure that when you sell and transfer the technology, it is actually used for those legitimate purposes and that it is used according to basic rule-of-law standards, such as surveillance only according to warrants issued by a court.”

Kaye and another UN expert, Agnes Callamard, the special rapporteur on summary executions and extrajudicial killings, said last week that the allegations involving Bezos’ phone were “a concrete example of the harms that result from the unconstrained marketing, sale and use of spyware.” Kaye described the current spyware trade as a “free for all” and, along with Callamard, called for a moratorium on the global sale and transfer of private surveillance technology.

Rory Byrne, co-founder of Security First, an organization that provides digital security advice to journalists and human rights activists, said he expected to see an uptick in episodes involving spyware as the technology spreads.

“The truth is, it’s becoming easier and easier and easier for governments to build the capability themselves or to just buy it off the shelf,” Byrne said.

Only a few countries — including the U.K., Germany, Austria and Italy — have any kind of legal framework governing hacking by law enforcement, said Ilia Siatitsa, legal officer and director of the government program at Privacy International. In 2016, a new law in the U.K. expanded and defined how police and spies in the country could hack devices, which it termed “equipment interference.” The tactic must be approved either by a senior police chief or a government minister and then, in most cases, additionally authorized by a current or former high court judge, known as a judicial commissioner.

In the U.S., the Federal Bureau of Investigation has since the late 1990s been using forms of spyware to gather information on electronic communication. The FBI has since secured expanded powers to hack computers across the U.S., as long as it has obtained a search warrant from a judge to use the method.

In most countries, however, “there is not a clear picture of what governments are permitted by law to do” in terms of hacking, Siatitsa said. “The fact is that we don’t even know which governments are engaging in this. It’s very problematic. It goes against the international human rights framework, which requires that if there’s interference with our privacy, it must be explicitly provided for by law.”

Demand for the technology has increased among law enforcement agencies, who have turned to hacking as a method of spying on encrypted messages sent using popular apps such as WhatsApp, Signal and Telegram, Kind said. But other factors have made the technology appealing, too. Hacking allows law enforcement and intelligence agencies to maintain constant surveillance on targets who frequently travel internationally, Kind added.

“Hacking tools allow you to get access to all the communications on a device no matter where the target is in the world, no matter what platform they are using or who they are communicating with,” Kind said. “That’s why hacking is so attractive to governments. It’s a single tool that they can use to get access to all communications on your phone at one easy point of access.”

Italy’s GR Sistemi is among the companies that have marketed surveillance technology, offering government agencies a spyware system named “Dark Eagle.” Company marketing brochures, which were published by Privacy International, say the technology could be used to hack phones and computers, providing “full interception of Skype and other encrypted communication software.” The Dark Eagle system can covertly capture images from a person’s webcam, record sent and received email, capture instant messenger conversations and monitor web traffic, according to the company’s documents. The company didn’t respond to a message seeking comment.

Israel’s Wintego Systems Ltd. has offered its customers a spy tool that it claims can intercept Wi-Fi traffic, steal their login credentials to their accounts, and extract “years of archived email, contacts, messages, calendars, and more,” according to company documents. A Wintego representative didn’t return messages seeking comment.

India’s ClearTrail Technologies, meanwhile, has marketed a system named Astra, which it describes as a “remote infection and monitoring framework” and promises “non-traceable payload delivery,” according to documents published by Privacy International. Once ClearTrail’s spyware is delivered to a computer or mobile phone, it can gather data stored on the device, including location, screen shots, Skype calls and search history, according to the documents. The company didn’t return a message seeking comment.

Similar spyware tools have also allegedly been developed by Israel’s MerlinX, France’s Nexa Technologies, California-based SS8 Networks Inc., according to company profiles and research reports, and Bloomberg News found at least a dozen other companies that appear to sell similar technology. MerlinX, Nexa and SS8 didn’t returned a message seeking comment.

In recent years, some spyware developers have come under fire because their products have been sold to authoritarian governments whose security agencies have used the technology to target political opponents and critics.

In 2012, for instance, Bloomberg News reported that a prominent human rights activist in Bahrain was targeted with spyware traced to the company FinFisher. In 2014, WikiLeaks used leaked documents to identify FinFisher sales worth €47 million ($52 million) to countries including Qatar, Bahrain, Pakistan, Vietnam, Nigeria, Singapore and Bangladesh. FinFisher, which didn’t return a message seeking comment, has previously said its technology is necessary in the fight against terrorism and serious organized crime.

Spyware sold by Israel’s NSO Group has been linked to hacks that have targeted human rights activists, journalists and politicians in countries including Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Mexico. Similar technology sold by Italy’s Hacking Team has been traced to hacks on activists and journalists in countries including Morocco, Ethiopia and the United Arab Emirates. Both companies have said they sell their equipment to law enforcement and intelligence agencies to fight crime and terrorism.

“Our products are only used to investigate terror and serious crime,” a NSO spokesman said in a statement last week. Memento Labs, which acquired Hacking Team, didn’t respond to a message seeking comment. But in a post on its LinkedIn page, the company said, “Memento Labs underlines its position in condemning any misuse of hacking technologies and capabilities, having always acted in compliance with all the relevant international laws.”

Governments that possess hacking technologies are likelier to use them to target high-profile individuals than ordinary citizens, according to Byrne, of Security First.

“You have to understand who is likely to target you,” Byrne said. “It’s important not to panic and become too paranoid.”

Gallagher writes for Bloomberg. William Turton of Bloomberg contributed to this report.

![Guitar heatmap AI image. I, _Sandra Glading_, am the copyright owner of the images/video/content that I am providing to you, Los Angeles Times Communications LLC, or I have permission from the copyright owner, _[not copyrighted - it's an AI-generated image]_, of the images/video/content to provide them to you, for publication in distribution platforms and channels affiliated with you. I grant you permission to use any and all images/video/content of __the musician heatmap___ for _Jon Healey_'s article/video/content on __the Yahoo News / McAfee partnership_. Please provide photo credit to __"courtesy of McAfee"___.](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/f4350ab/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1600x1070+0+65/resize/320x214!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F60%2Fef%2F08cda72f447d9f64b22a287fa49c%2Fla-me-guitar-heatmap-ai-image.jpg)