Column: Pharmacy middlemen claim to keep prescription prices low. In fact, they’ve cost consumers billions

- Share via

In 2022, an executive of a big pharmacy middleman firm acknowledged the noxious reality of its business model:

It was designed to massively overcharge customers by steering them to its affiliated or “preferred” pharmacies or its home delivery subsidiary.

Referring to a generic version of Gleevec, a leukemia drug taken by nearly 200,000 patients, the executive noted in an internal memo that “you can get the drug at a non-preferred pharmacy (Costco) for $97, at Walgreens (preferred) for $9000, and at preferred home delivery for $19,200.... We’ve created plan designs to aggressively steer customers to home delivery where the drug cost is ~200 times higher.”

PBMs are not lowering prices for drugs used by patients to treat severe diseases like prostate cancer and leukemia.

— Federal Trade Commission

The executive concluded, “The optics are not good and must be addressed.”

What that memo described, according to a new report from the Federal Trade Commission, is standard operating procedure among the nation’s largest pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Originally devised in the 1960s as intermediaries helping health insurers process claims, steering doctors and hospitals to the cheapest drug alternatives and giving insurers greater leverage in negotiations with drug manufacturers, they soon became just another special interest in America’s fragmented healthcare system.

Thanks to a wave of consolidation and growth of healthcare conglomerates, the FTC says, the three largest PBMs manage nearly 80% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. They have accumulated enough power to profit “by inflating drug costs and squeezing Main Street pharmacies,” driving the independents out of business.

Once posed as an answer to high drug costs, they’re today at the hub of a system that drives up drug prices for consumers.

The CEOs of drug retailer CVS and health insurer Aetna were marvelously in sync Sunday when they jointly announced their companies’ $69-billion merger deal.

Starting in the 1990s, some of the biggest PBMs were acquired by drug companies, creating conflicts of interest that led to federal orders for divestment.

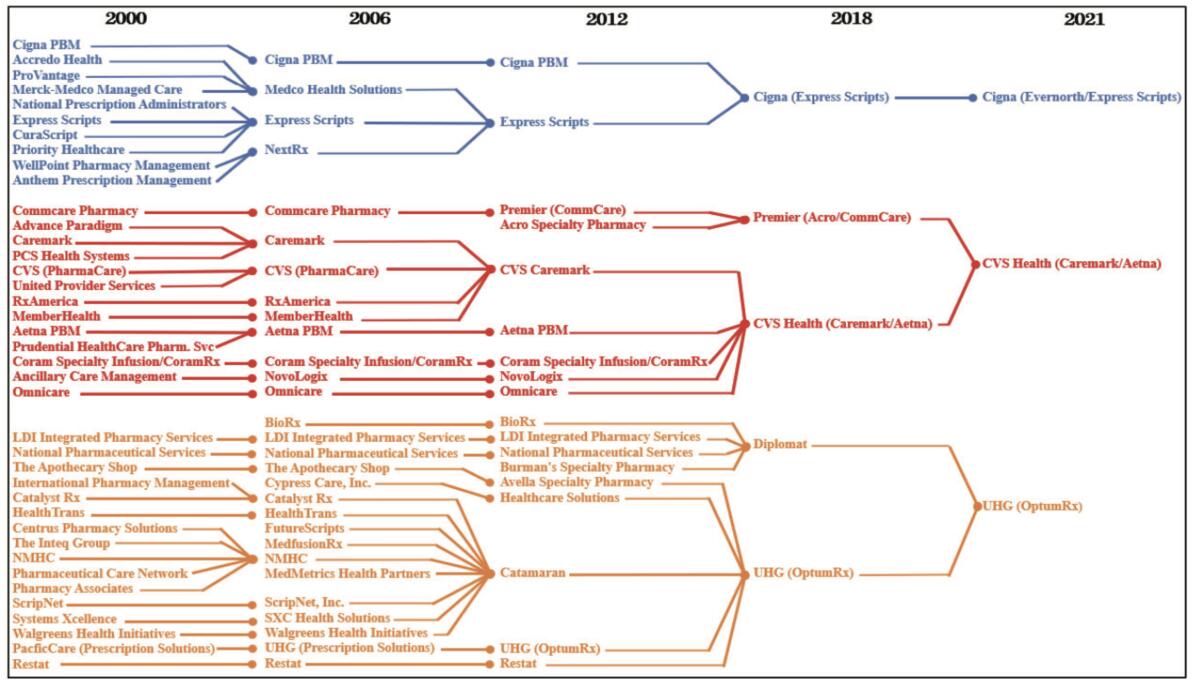

Then came a wave of mergers and acquisitions within the PBM universe, followed by acquisitions by insurers and pharmacy companies — CVS acquired Caremark, then the biggest PBM, in 2007 and UnitedHealth merged CatamaranRx, then the fourth-largest PBM, into OptumRx in 2015.

Between 2000 and 2021, 39 individual healthcare companies — drugstore chains, health insurers, managed care firms and PBMs — all coalesced into three healthcare behemoths, Cigna, CVS and UnitedHealth.

CVS Health Corp. owns not only the Caremark PBM, which controls 34% of the prescription market, but the insurance company Aetna and about 9,000 retail drugstores.

Cigna Group, which has a prescription market share of 23%, owns the mail-order PBM Express Scripts and the Cigna insurance company. UnitedHealth Group is the largest U.S. health insurer and owns 1,000 walk-in health clinics as well as physician groups; through its OptumRx PBM, its prescription market share is 22%.

Along with Humana, the fourth-ranked PBM with a market share of 7%, those conglomerates produced combined revenue of $456 billion in 2016, 14% of national health spending. Today, they collect more than $1 trillion in revenue, or 22% of U.S. healthcare spending.

Despite the predictably anticompetitive effects of these mergers and acquisitions, not a single one was challenged by antitrust enforcement agencies, says the FTC — one of the antitrust regulators asleep at the switch.

Among the stratagems employed by PBMs to boost profits, the FTC says, is steering health plans and patients to their own affiliated pharmacy chains.

Some patients have discovered that their drugs won’t be covered by their insurers unless they buy them at specified pharmacies, the result of deals the PBMs have made with insurers, including those with which they share a parent. But the customers may have to pay more out of pocket at the affiliated pharmacies than they would at an independent.

Diabetes doctor Irl B.

The FTC staff found that for “specialty prescriptions” — a designation the PBMs place on certain drugs, often without explanation — 55% were filled at affiliated pharmacies. The same ratio didn’t occur with prescriptions under Medicare’s Part D prescription coverage, because federal law requires that those prescriptions can be filled at almost any licensed pharmacy. Only 22% of Part D prescriptions were filled at PBM-affiliated pharmacies. That suggests that PBMs may be steering patients to their pharmacies where that’s not forbidden by law.

The statistics were drawn from submissions by two of the three top PBMs, which are unidentified. The third didn’t submit the necessary data.

The FTC also touches on a relatively new wrinkle in drug pricing — rebates by drugmakers to PBMs in order to gain preferential positions in drug formularies.

The agency says its review of contracts between manufacturers and PBMs shows that some drug companies promise PBMs higher rebates if the latter exclude competing drugs from their formularies — including generic versions that are chemically identical to the brand-name products — or require prior authorization before covering the rival drugs.

Indeed, the FTC is reportedly preparing to sue CVS, Cigna and UnitedHealth over their PBMs’ tactics in negotiating rebates with drugmakers, specifically for insulin. The cases are still in the planning stage and their timing isn’t known.

Predictably, the big PBMs and their lobbyists find much to dislike in the FTC report, which the agency describes as an interim staff report, part of an investigation launched in 2022.

A spokesperson for Cigna’s Express Scripts criticized the report for “blatant inaccuracies” (but didn’t offer specifics in an email to me). A spokesman for CVS blamed drugmakers for high prescription prices, stating that an FTC effort to “limit the use of PBM negotiating tools would instead reward the pharmaceutical industry.” Optum didn’t reply to my request for comment.

J.C. Scott, president of the Pharmaceutical Care Management Assn., the PBM lobbying arm, accused the FTC of advancing “pre-determined conclusions ... irrespective of the facts or the data.”

The pharmacy chains have discovered that taking a larger role in the healthcare system than simply dispensing prescriptions and selling over-the-counter notions is more complicated and costlier than they expected.

Drawing from more than 1,200 comments submitted by stakeholders in healthcare and by other members of the public, the agency outlined a host of methods PBMs are accused of using to benefit their affiliated services, block patient access to inexpensive generics and pocket discounts that should properly go to customers.

The FTC also mined lawsuits, including a 2023 case the state of Ohio filed against Express Scripts, charging that the PBM exploits its knowledge that “Ohioans in need of medication, particularly life-saving medication, will pay the asking price. The choice is binary — pay or suffer.”

Drug manufacturers capitulate to the PBMs’ rebate demands, the lawsuit says, to avoid being dropped from the PBMs’ formularies, the rosters of drugs that they’ll cover. “Patients pay more, manufacturers get less, and the PBMs profit. Handsomely.”

PBMs have been the targets of drug industry participants for years — sometimes fingered by drugmakers or insurers to deflect accusations that they’re responsible for prescription drug inflation.

It may be true that all those entities share the blame for high prices. Over the last couple of decades, however, all have become tentacles of the same octopus. The consolidation of drug chains, physician groups, insurers and PBMs into conglomerates has made it much harder to identify responsibility for drug inflation.

Contracts between PBMs and unaffiliated pharmacies, the FTC says, are “opaque, complex, and conditional, making it challenging to understand what pharmacies will ultimately be paid for any given drug.” The result is that smaller, nonchain pharmacies may get pushed out of the market, “leading to higher costs and lower quality services for people around the country.”

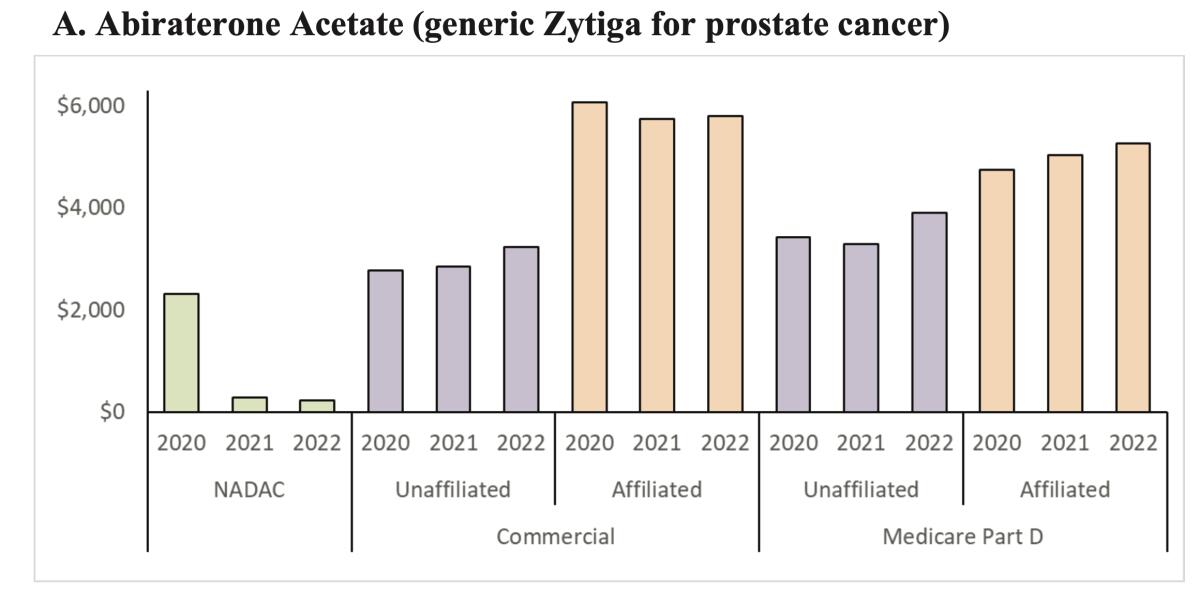

The FTC report offers two case studies involving generic cancer drugs in which the agency says PBMs reimbursed their affiliated pharmacies more for prescriptions than unaffiliated pharmacies, yielding nearly $1.6 billion in gross profits from 2020 through mid-2022 for those affiliated pharmacies over the national average of those drug costs.

The drugs are a generic version of Zytiga, a treatment for prostate cancer, and a generic for Gleevec, a drug for leukemia. The high reimbursement rates for druggists dispensing those drugs may “translate into high out-of-pocket costs for patients,” the FTC says. In other words, “PBMs are not lowering prices for drugs used by patients to treat severe diseases like prostate cancer and leukemia.”

Magnify the gains on those two drugs by the potential profits the PBMs may be extracting from the entire spectrum of prescription pharmaceuticals, and the toll becomes breathtaking.

“It appears that PBMs are having the commercial health plans and Medicare Part D prescription drug plans they manage pay their affiliated pharmacies rates that are grossly in excess” of national average prices or prices paid to unaffiliated pharmacies.

No one escapes the consequences of this sort of market manipulation. The internal transactions, largely hidden from the public and regulators, may distort the statistics that health plans submit to the government to show they meet the coverage standards required by the Affordable Care Act, allowing the conglomerates to “game” the rules, the FTC says.

They may drive up healthcare costs for self-insured clients such as large companies, which may pare back health coverage for their employees as a result.

They can raise co-pays for patients, lead to cutbacks in the availability of coverage for some drugs, or prompt patients to ration their prescriptions, risking their health to save money. To the extent they affect Part D, they may drive up government spending.

To quote the Ohio lawsuit, PBMs were created as a counterweight to perceived profiteering by Big Pharma. But once they “grew powerful enough to themselves extract exorbitant fees ... the solution became the problem.”

The FTC says it issued its interim report because several PBMs haven’t provided the agency with the information they’re required to submit, hindering its ability to complete its investigation.

At the very top of the report, the FTC warns that the firms better come across “promptly,” or they’ll be taken to court. The FTC should start suing now, because the PBMs’ apparent code of silence raises a familiar question: What must they be hiding?

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.