Here’s something you might not know about how colleges hand out financial aid

- Share via

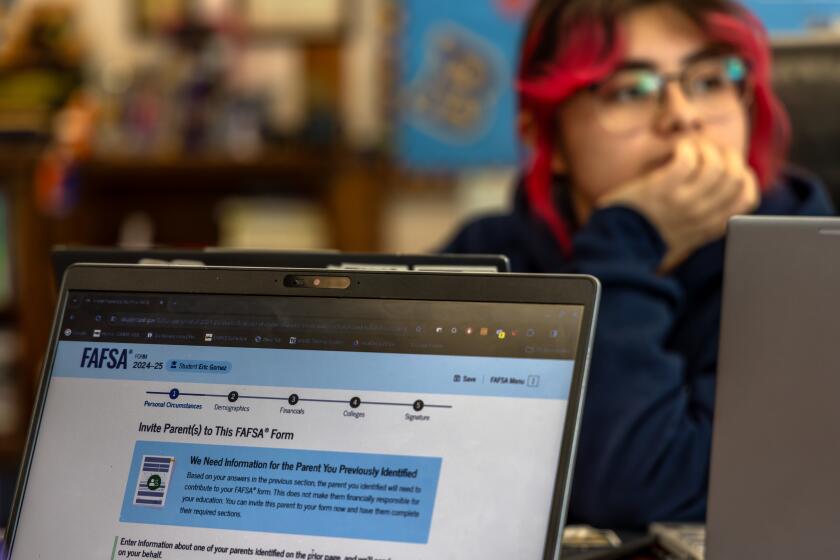

Dear Liz: After the pandemic started, we received money from the federal government and decided to put it in a custodial account for our son, starting when he was 14. We invested the money in a Standard & Poor’s index fund. I now think I made a mistake and should have simply added the money to the 529 college savings plan we have for him. Can I close the custodial account and transfer the money to the 529? If so, what is the process? Another benefit I see to doing so may be that the funds might not be considered in financial aid calculations. He will not qualify for aid based on need as we are financially well-off but he may qualify for aid based on merit.

Answer: You can transfer the funds from a custodial account, but contributions to 529 college savings plans have to be made in cash. That means you’d have to sell the index fund, which likely means paying a tax bill on the gains.

If your primary concern is financial aid and your family won’t qualify for need-based help, then there may be little reason to incur that tax bill right now. The merit aid you’re hoping to get won’t be affected by where you save. Merit aid isn’t based on your financial situation but is instead an incentive to attend the school and reflects how much the college wants your kid.

Need-based aid, by contrast, can be profoundly affected by custodial accounts, which are considered the student’s asset. Because 529 plans are treated much more favorably by need-based formulas, a transfer could make more sense. If there are a lot of gains in the custodial account, though, parents would be smart to get a tax pro’s advice before making this move.

With college expenses looming, consider picking up a copy of “The Price You Pay for College: An Entirely New Road Map for the Biggest Financial Decision Your Family Will Ever Make,” by New York Times personal finance columnist Ron Lieber. The book offers a comprehensive but readable guide to a fraught, potentially expensive process.

The rollout of the new, ‘simpler’ FAFSA application is unacceptably chaotic. There’s plenty of blame to go around.

Naming beneficiaries turns tricky

Dear Liz: I have spent the majority of the last three decades abroad. Relationships fade away if there is little contact. Such is life. Most of the financial accounts that I have allow me to provide an organization as a beneficiary. But some institutions, like TreasuryDirect, require an actual person to be listed as a beneficiary. I have approached some acquaintances to ask if they would like to be my beneficiary, but as soon as I say I need their Social Security numbers, they think that I am trying to scam them. My bizarre question is: Whom can I leave my money to?

Answer: If you don’t name a beneficiary for your U.S. savings bonds, they become part of your estate when you die.

The proceeds can be distributed according to your will or living trust. This may require the court process known as probate, but whether that’s a big deal depends on where you live and the size of your probate estate. Many states have simplified probate that can make (relatively) short work of small estates.

If your savings bond holdings aren’t substantial and your other accounts have beneficiaries — which typically means they avoid probate — then this could be a reasonable approach.

Another option is to create a living trust and have the bonds reissued to the trust, said Burton Mitchell, an estate planning attorney in Los Angeles. Living trusts involve some costs to set up, but they avoid probate and they’re flexible.

“The reader can then modify the living trust whenever desired without re-titling the financial accounts,” Mitchell said.

If you report check fraud to your bank promptly — typically within 30 to 60 days of your statement date, depending on state law — then you should be made whole.

Junk fees for online payments

Dear Liz: You recently answered a question about fees for paying bills online. I agree that the $12 fee mentioned is too high but I also know that any platform costs money to maintain. I work for a nonprofit that takes donations and our donors can choose to pay the fee. I doubt regular customers would agree to pay a corporation’s fees by choice.

Answer: The key word here is “choice.” Your donors are volunteering to chip in a little extra to help a charity. The letter writer was facing a $12 fee to securely pay an insurance bill online, when the alternative is to send a check through the (insecure) mail. Most companies have figured out that online payments are better for all concerned and are trying to encourage their use, rather than sticking consumers with junk fees for using this option.

Liz Weston, Certified Financial Planner, is a columnist for the Los Angeles Times and personal finance website NerdWallet. Questions may be sent to her at 3940 Laurel Canyon, No. 238, Studio City, CA 91604, or by using the “Contact” form at asklizweston.com.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.