U.S. strikes Yemen: Are L.A., Long Beach ports ready for cargo surge?

- Share via

The ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, the nation’s largest cargo complex, are bracing for a business surge created by problems elsewhere: the Suez Canal in Egypt — a sudden hot spot in a potentially widening Mideast conflict — and the Panama Canal, plagued by prolonged drought.

The canals are two of the world’s most important trade gateways. When the interconnected global supply chain gets tangled, the knots cause costly delays as retailers and manufacturers look for alternate routes to get their freight to consumers and factories.

The Suez and Panama canals also are options when shippers fear relying solely on Los Angeles and Long Beach, which weathered a series of pandemic-related backlogs and other problems starting in March 2020.

But with labor peace returned to the Southern California docks — longshore workers ratified a new contract last year after months of disruptions — lost business has returned, port officials say, and there’s plenty of capacity for more. Also past are the COVID-19 days, when U.S. consumers’ online shopping binges created a massive traffic jam in San Pedro Harbor, giving ports on the East and Gulf coasts a chance to grab cargo away from Southern California.

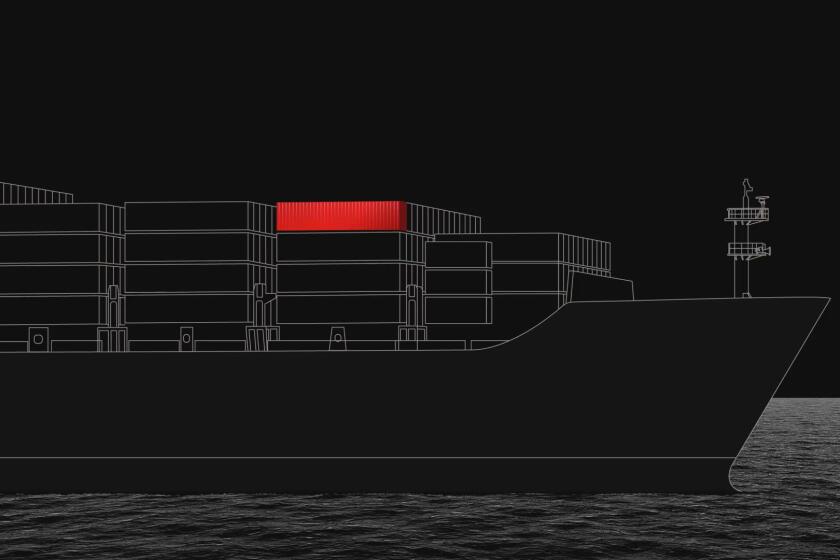

The back and forth matters because the ports are a key economic engine in Southern California, affecting not only dockworkers but those who drive trucks, staff warehouses and labor elsewhere in the sprawling distribution and logistics network. The L.A. and Long Beach ports combined handle nearly 40% of U.S. imports from Asia that arrive in metal shipping containers aboard vessels whose length is nearly equivalent to the height of the Empire State Building.

The East Coast’s busiest port complex has periodically proclaimed itself the nation’s largest for container cargo. The myth could cost California foreign trade jobs.

“Very few people had Houthi rebels disrupting the global supply chain on their bingo card,” said Salvatore Mercogliano, a maritime historian at Campbell University in North Carolina and host of a YouTube channel called “What is going on with shipping?”

On Friday, Yemen’s Houthi rebels promised retaliation for U.S. and British strikes launched Thursday. President Biden said the bombings followed diplomatic attempts to end the militant group’s attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea as the vessels head toward the Suez Canal.

So far, local ports are seeing more of an effect from problems at the Panama Canal than those in the Red Sea, “and we’ve been able to handle it,” said Mario Cordero, the Long Beach port’s chief executive.

“We’ve stepped back, and lessons have been learned since we had the backlog, and we’re more prepared to go to 24/7 operations if we need to than we have been in the past,” Cordero said. “We are very fluid. We are doing well, and we can handle more.”

Because of the Suez disruptions, many insurers decided that it was safer to send ships on a much longer and more expensive trip south, along the coast of Africa and through a storm-swept passage, to get to ports on the Eastern Seaboard and U.S. Gulf Coast. South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope (a long-ago Pope thought it was a friendly name) is known as the Graveyard of Ships; Southern California is seen as more hospitable, shipping experts said.

Gene Seroka, executive director of the L.A. port, about to leave on a 10-day trip to Asia to search for potential customers, spoke of laying groundwork in Indonesia, Vietnam, India and other countries to “fine-tune that relationship of trade.”

“Now we’ve got a real opportunity to look at pushing cargo away from the Suez and back to the West Coast,” he said.

Retailers and manufacturers have shifted cargo away from the L.A. and Long Beach ports, threatening local jobs. The ports vow to bring that trade back, but it won’t be easy.

The Panama Canal was expanded in 2016 to accommodate bigger cargo ships so that customers could take advantage of investments by ports on the U.S. East and Gulf coasts, which were eager to attract cargo that previously landed in Southern California, then moved east by truck and train.

But an extreme drought has dramatically reduced the level of the freshwater artificial lake that helps fill the canal’s locks and is an important source of drinking water and agricultural irrigation. Shippers were willing to pay as much as $4 million to jump ahead of congestion, according to Bloomberg, although that fee recently dropped to less than $270,000 as tankers and cargo ships found other routes.

The arrival of warmer weather patterns from El Niño is expected to worsen the drought, just as the region is entering its traditional dry season.

The Panama Canal had been allowing more than 40 ships a day to pass through on their way to the U.S. Gulf and East coasts. Canal operators have cut that number in half, creating a backlog of ships.

“It’s another disruption,” said Jonathan Gold, vice president for supply chain and customs policy for the National Retail Federation. “It’s another impact on the supply chain, and it was supposed to be an easy gateway for trade but now has restrictions.”

Seroka said the Port of Los Angeles is running at 75% of capacity and is at pre-COVID levels.

“So not only do we have capacity to grow, but we’ve also got the bottlenecks and the backlogs worked out of the system,” he said. “We took what we learned from the COVID surge and tried to apply it day in and day out.”

Follow a container of board games from China to St. Louis to see all the delays it encounters along the way.

Consumers, meanwhile, are likely to feel shipping delays in their wallets.

“Going around the [Cape of Good Hope] is not sustainable,” said Tyler Reeb, interim executive director of Cal State Long Beach’s Center for International Trade and Transportation. “That’s particularly because these ships are huge, and they have to stop and refuel. They are going to do that in South Africa; fuel’s very expensive there.

“The bigger issue is that we have gotten ourselves out of high inflation, and this is a very inflationary-looking solution,” he added.

Reeb said that going around the cape adds 10 to 15 days to a ship’s journey.

“That’s time and money, and that’s what leads to more challenges for retailers,” he said. “They’re not going to get their goods they need in time on their shelves, and it will be challenging.”

All of that plays up Southern California’s geographic advantage, according to Mercogliano.

“You’re adding 3,500 miles to the trip and paying for an extra million dollars in fuel,” he said. “What’s beginning to happen now is shippers are saying, ‘OK, put my box on a ship for L.A., for Long Beach.’”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.