- Share via

As I was scrolling through TikTok the other day, I received a text from a friend.

“I take back everything bad I said about TikTok Shop,” she said. “I just bought a Staub Dutch oven for like $100. And it’s normally like $400.”

I had no idea what a Dutch oven is used for, but I thought I might need one too. I mean, I had to at least check — the deal was too good to be true. Thankfully, I came to my senses and did not buy one.

But I did spend almost $100 on other items from TikTok Shop that day.

Ever since TikTok officially launched its in-app shopping feature in the U.S. in September, it’s quickly turned the video-scrolling app into a budding e-commerce marketplace. The new feature sells about $7 million worth of products a day in the U.S., with a goal of reaching $10 million a day by the end of the year, the Wall Street Journal reported last month.

As the Biden administration weighs a ban on the app, many budding entrepreneurs fear losing a tool that has helped them build a robust customer base.

Although TikTok Shop has a ways to go before it can truly match up to the likes of e-commerce giant Amazon in terms of sheer volume, customer trust and delivery logistics, what it does have is unparalleled command over eyeballs.

TikTok has 150 million users in the U.S., 35% of whom are ages 18 to 24. Teens in particular spend an average of nearly two hours a day on the app.

And TikTok Shop is proving to be remarkably effective at turning that screen time into shopping time.

Psychological warfare

It’s impossible to spend any amount of time on TikTok these days without encountering an ad or a video that has a product linked for commission.

And not just any product. I routinely see the same slew of items — specifically targeted to blend into my feed of fashion, mental health and art content — over, and over, and over again until I could practically market them myself.

A brown faux leather shoulder bag, big enough to carry someone’s laptop, a few books, phone, wallet. The Beachwaver, a rotating curling iron that will curl your hair in minutes. A shadow work journal to help you heal your inner child. The OQQ three-piece women’s body suit that will cinch your waist, even if you just gave birth. A 100-color watercolor set that comes with 35 metallic colors and three water brush pens.

Repetition as a promotional strategy is nothing new, but on TikTok Shop it feels like a form of psychological warfare. I’m losing the battle — or at least my credit card is.

This endless onslaught of product videos is being generated by a growing number of creators who almost exclusively focus on recommendation or review videos. They talk directly into the camera while unboxing or trying out a new product. They’re chatty and affable, and they seem like regular people who are genuinely recommending something they’ve found useful or enjoyable in their everyday lives.

TikTok’s design encourages manic performance and a false sense of intimacy — all of it obscuring the power of its invisible algorithms.

Now one video on its own isn’t going to persuade me to buy something, but scrolling through 10 or 20 videos featuring real-life testimonials about the same product might be enough to get me to cave.

“This is the toner that was ranked No. 1 in Korea for months and months and months and months,” a woman tells me knowingly, her hair freshly wet from the shower and two white toner pad squares on her face. “When I was in Korea I stocked up back in March.”

She held up a bottle that I had already seen recommended by two other accounts. All three women had smooth, shiny plump skin — the kind of skin that stays tantalizingly out of reach for me.

Los Angeles creator Dina Asprer said she doesn’t consider herself an “influencer” or a “TikTok person” but had always been passionate about Korean skincare, having lived in South Korea for five years after college.

The 31-year-old quit her banking job during the pandemic to spend more time with her kids and only made TikToks for fun. She started putting links to products in her videos in June when the option became available to some users.

One particular item took off — a snail mucin essence from popular Korean brand COSRX. At one point, she was earning commissions from selling 600 bottles a day, and now still sells around 1,000 bottles a month.

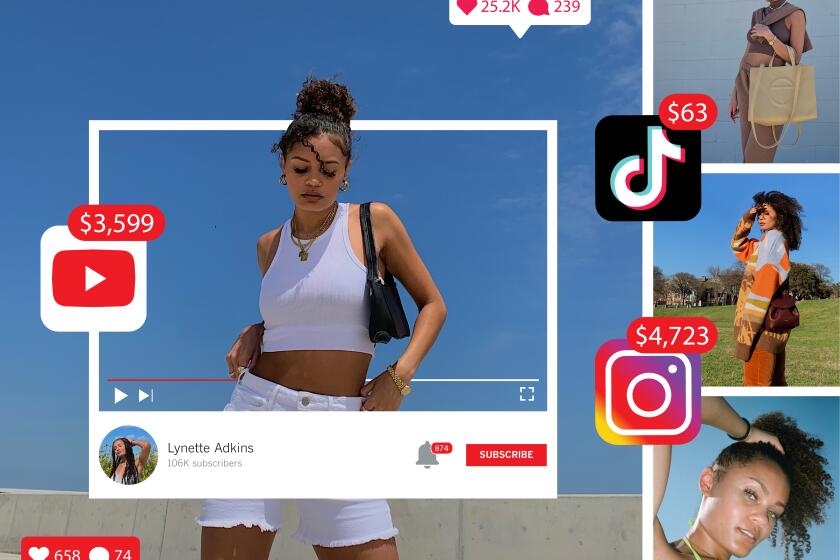

Meet Lynette Adkins. She’s part of a new crop of creators focusing their content on the how-to of the business: making money from an online following.

“I never considered this as a job, but I’m starting to take it more seriously,” Asprer said. She’s even attended a few workshops that TikTok offers to help creators grow, traveling to its office in Culver City.

In another video that pops up on my feed, a woman demands my attention.

“Listen to me,” Katelyn Beaupre says urgently. “If you have eczema or dry skin, I’m about to put you on.”

I don’t have either, but for some reason, this information feels important to know.

Beaupre explains that she works at a daycare and has OCD, which means her hands are extremely dry from washing them frequently. Other products made her hands greasy, but this one — which she purchased after seeing it all over TikTok — was so good she was bringing it in for her co-workers to try.

“I was a little skeptical at first because I really didn’t like the smell,” Beaupre says. “To me, it smells like oregano.”

That video, featuring a lotion by the brand the Ocean Healed My Eczema, has 3.6 million views. She posted about it a few more times. Last month, she made about $20,000 in commissions.

The 22-year-old from Massachusetts has a little more than 95,000 followers on TikTok and makes videos when she has time, outside of working at a preschool full time and going to school part time. But the commissions she’s earned in the last two months has helped her to pay off her credit card debt and student loans.

Worsening economic conditions could be a stress test for the burgeoning influencer economy. But online creators are pivoting by telling viewers what not to buy.

Commissions range from 20 cents to $7 a purchase and can fluctuate if a certain product, like the rotating curling iron for example, starts trending, leading to more influencers making videos about it, Beaupre noticed.

“Sometimes I try to go for things that are a little bit higher in commission,” she said.

She also indicates in her profile that she’s a “UGC + lifestyle creator,” which means her videos are available for companies to use as user-generated content in paid TikTok ads.

The eczema lotion that Beaupre promoted first offered a $4.99 commission, or 20% of the price, before the amount was lowered to closer to $3.

Maybe that’s why there are countless other videos of creators raving about the very same product. Yet they still feel honest. People showed before-and-after pictures of their hands, legs and elbows, some using it for eczema and dry hands and others for psoriasis.

The company has made it simple for sellers to make products eligible for commission and creators to request free products and post videos with a direct link to generate sales, streamlining a process that otherwise might have required more business-savvy from both sides. TikTok Shop has just two requirements for commission-eligible creators: you must be over 18 and have at least 5,000 followers.

Gen Z’s QVC shopping channel

Every week, Brandon Hurst sells more than 1,200 plants from his 800-square-foot apartment in Van Nuys.

He carefully packages each one — golden pothos, string of hearts, trailing hoya — with a small team of employees, slaps on a bright sticker that reads “live plants,” and ships them across the country. Then the next batch arrives at his apartment, ready to be sold.

His secret? Live selling.

Hurst makes a majority of his sales through TikTok livestreams every Friday, Saturday and Sunday, when he greets loyal customers, welcomes newcomers and talks about the plants available in his shop. He joined TikTok Shop in April before its formal launch, and he’s sold more than 30,000 plants since — more than the number he sold in the three years before joining the platform.

“I try to turn it into kind of like a show, a little bit like QVC,” Hurst said of his livestreams. “Literally within the first five minutes, we already are at like 10 or 15 orders. It’s incredible.”

The story of how the internet was made doesn’t begin and end with Silicon Valley. It runs right through Hollywood.

Although he already had viral plant videos on the app before joining TikTok Shop, it “didn’t equal sales the way that it now can, with the link right there in the video,” Hurst said.

Live selling online first emerged in China several years ago and exploded during the pandemic. Two-thirds of Chinese consumers purchased a product via livestream within the previous year, according to a 2020 survey.

In 2022, an estimated $500 billion in goods were sold via livestream in China, accounting for about 23% of all e-commerce sales in the country, according to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Two of China’s top live-streamers were able to sell $3 billion worth of goods in one day in October 2021.

Although the phenomenon hasn’t quite reached that scale yet in the U.S., platforms like Amazon, EBay and Poshmark have all launched their own live shopping features. The U.S. live selling market was expected to reach $32 billion in sales this year.

Whenever I scroll through TikTok these days, I stumble upon at least one livestream pitching me a product I didn’t know I needed.

Lately, it’s been a fast-talking man extolling the virtues of an electric scrubber. As he demonstrated its efficacy on a shower door recently, I pondered whether I should be deep-cleaning my bathtub.

“Thank you for your new orders, thank you thank you,” he said as he aggressively rang a bell. “You are doing a fantastic job.”

Next, a woman was holding up the OQQ bodysuits that have been viral on TikTok for a while. I had been thinking about buying them for months. She wore one herself, as did another model who slipped in and out of frame.

“Go ahead and snag them while they’re hot for sure,” she said. “We are already selling out today.”

I entered my height and weight into the chat to ask what size I should purchase. I was surprised to hear her address me by name.

“Jaimie, we’re out of stock of the extra small, so I’d go with the small,” she said. With her blessing, I tapped “buy,” selected my size, and checked out with Apple Pay.

Thirty seconds later, my brain humming from the dopamine hit, I’m back to scrolling through my usual TikTok feed and looking for the video that will pique my interest next.

Pitching the pitchers

I did not make my first purchase on TikTok Shop without a fair bit of skepticism.

Were all these products low-quality, drop-shipped items from overseas? Were they cheap knockoffs from unknown Chinese companies, like many listings on Amazon?

The social app’s Shop marketplace, key to its growth strategy, is so far hard to navigate.

Given some of the cut-rate prices, I couldn’t help but draw comparisons to companies like Shein, Temu, AliExpress and Wish, where it’s often a toss-up whether the item you just ordered will be of durable quality or complete junk.

The biggest barrier to more widespread adoption of social e-commerce is consumer trust, said Laura Gurski, North America commerce lead at Accenture Song. This is especially true among people in older demographics who are used to buying from reliable retailers and brands.

This is why sellers earnestly pitching their own products can do so to such great effect through TikTok videos. They’re in part borrowing tactics you might see on shopping channels like QVC, where trained hosts create intimacy with the viewer by gushing over products like they’re gossiping with a friend. But unlike perfectly polished QVC hosts in a studio, the TikTok entrepreneur is unfiltered and up close — sometimes even awkwardly so — right there on your phone screen.

Father-son duo Michael and Daniel Jay of San Diego started their brand Lazy Butt Club as a revamp of Michael’s old T-shirt designs from decades ago. They went from less than 100 orders a year to 3,000 in a few weeks after their first viral TikTok video in 2021.

“Ever since we switched to being more personal and showing you what we’re doing and our story, it’s been a lot easier to resonate with people,” said Daniel, who runs the TikTok account.

In one video, I watched Michael pull one of his hand-drawn rough drafts of a T-shirt design out of a box. In another, he screen printed “Tyrannosaurus Wrecks” onto a crew neck, telling viewers that it would be the first one he’s printed in 25 years.

They joined TikTok Shop over the summer, generating a few thousand orders since then through both the platform and their website. It’s opened up new avenues of business for them.

“One of the intimidating things about trying to work with influencers is having that business side already figured out, like how to pay them,” Daniel said. “I kind of didn’t even know how to formulate a message and ask people, like how much should they get paid or whatever.”

Sellers like the Jays help TikTok establish trust, so the platform has been aggressively courting them with a variety of incentives, such as covering the cost of free shipping for some buyers and offering frequent sales and coupons.

“When we first signed up, we were like, wait — free shipping, like what do you mean free shipping? What is this sale?” Daniel said. He was amazed to learn that a customer could purchase one of their shirts for as low as $8, while his company received the full price.

With all the perks, several sellers said they don’t even list items on Amazon because they consider the process too complicated or time-consuming, and the site generates too few sales.

Chief Executive and founder Jay Nagy launched the Ocean Healed My Eczema in July directly on TikTok Shop.

In just three months, he said, he’s sold more than $1 million worth of eczema cream through the platform. It went viral with the help of creators like Beaupre, and through Nagy’s videos about his own experience with eczema.

“TikTok Shop is so smart, it just puts it in front of the right people. It’s really wild,” Nagy said. “They gave me the platform to really tell my story with my struggle with eczema.”

When I first discovered Nagy’s product, it was through a series of videos from creators that appeared during my daily TikTok binge-scrolling session. I have watched enough testimonials — more than 10 — to be convinced of its effectiveness.

But I haven’t bought the cream.

After all, I don’t have eczema.

So I obviously don’t need it.

Right?

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.