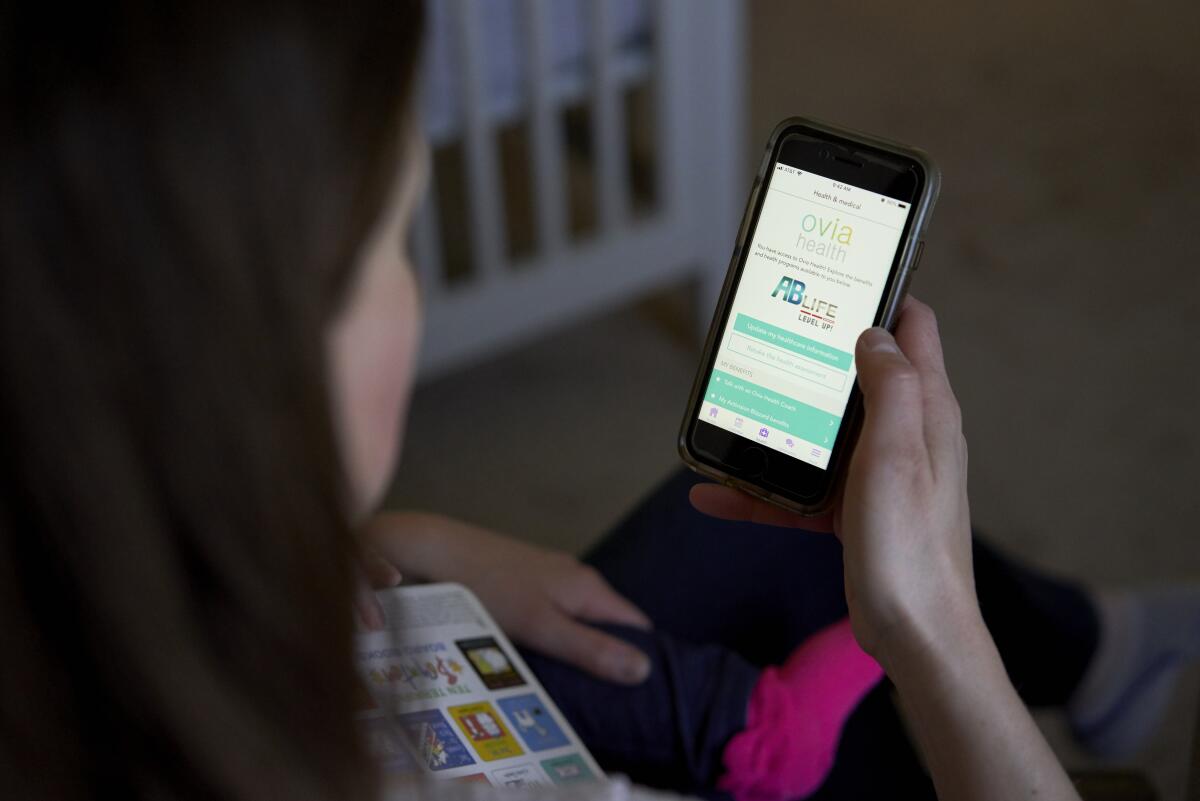

How data from period-tracking and pregnancy apps could be used to prosecute pregnant people

- Share via

Many popular reproductive health apps are lacking when it comes to protecting users’ data privacy, according to a new report highlighting the potential legal risk to people seeking an abortion.

After studying 20 of the most popular period-tracking and pregnancy-tracking apps, researchers from the nonprofit Mozilla Foundation found that 18 of them had data collection practices that raised privacy or security concerns. The report also considered five wearable devices that track fertility but did not raise concerns about their data collection.

Many of the apps had vague privacy policies that didn’t spell out what data could be shared with government agencies or law enforcement, said Jen Caltrider, lead researcher for Mozilla’s “Privacy Not Included” buyers’ guide for connected consumer products, which produced the report.

Ideally, she said, companies would publicly commit to handling data requests from law enforcement by requiring a court order or subpoena before handing over any data, working to narrow requests as much as possible and alerting users about any requests, she said.

Glow Inc., which makes four of the apps Mozilla rated as having privacy or security concerns, said in a statement that the company does not share personal data with anyone and “will never sell” user data. The company also said it has an “extensive” set of features to protect user data, undergoes annual privacy and security assessments conducted by a third party, and that employees go through privacy- and security-related training.

Other companies listed in the report emphasized their commitments to data privacy in response to queries from The Times. Clue, which received an unfavorable privacy and security rating, said in a statement from May that “we will never turn your private health data over to any authority that could use it against you.” Apple, whose Apple Watch was not rated as a privacy concern, said health data is encrypted when synced to iCloud or when a phone is locked with Face ID, Touch ID or a passcode. And Natural Cycles, one of the few apps that received a favorable privacy and security rating, said in a statement that the company is “of the mindset that every app — even if they have strong privacy protections like ours — should be working even harder to protect data on their user’s behalf.”

The Euki app, which received a favorable rating from Mozilla, was based on two years’ worth of research into what potential users wanted to see in a sexual and reproductive health app, said Caitlin Gerdts, vice president of research at Ibis Reproductive Health. A major concern was privacy and security, she said.

“Privacy and security concerns in the realm of reproductive health are not new,” Gerdts said. “Many communities, especially over-surveilled and overpoliced communities, have been experiencing these concerns for a long time, and of course now, it’s at the forefront of even more people’s minds.”

Experts have said health data input into most period-tracking apps isn’t subject to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, also known as HIPAA, which regulates how health providers and other entities must treat patients’ data. A vague privacy policy can mean users won’t know what data are being shared, with whom and under what circumstances, forcing users to blindly trust a company to protect their information.

“It gets really gray and really slippery very quickly,” Caltrider said. “It’s really hard to be certain exactly what is being shared and with whom.”

That could be a concern in states that moved to prohibit abortion after the Supreme Court’s reversal of the landmark Roe vs. Wade decision.

On TikTok and Instagram, pregnant women find themselves targeted with videos that prey on their worst fears as expectant mothers, from birth defects to child loss. For some, quitting social media is the only solution.

Residents of California, where abortion remains legal, do get some protection through the state’s data privacy laws. Californians have the right to access, delete and opt out of the sale and sharing of their personal information.

“Small health apps that are collecting health information or even the Fitbit that your doctor tells you to wear may not be covered under HIPAA, but they are most likely covered under the California law,” said Ashkan Soltani, executive director of the California Privacy Protection Agency, which implements and enforces the state’s consumer privacy laws.

And starting next year, Californians will have additional protections, such as restrictions on a company’s ability to collect data for purposes other than its main function.

These laws apply only to California residents, not to out-of-state travelers who might come to California seeking an abortion. It may, however, give California consumers who travel to other states additional protections on their data, Soltani said.

The drug Makena doesn’t reduce the risk of preterm birth, a study found, and the FDA recommended it be taken off the market. Its maker has refused.

In addition to vague privacy policies, the Mozilla report also found that some apps allowed weak passwords or were not clear on how algorithms used to predict ovulation and fertility time frames operated.

Consumers often want to but don’t know how to protect their privacy or don’t see immediate harm from not doing so, Caltrider said. But as the monetization of user data only continues to increase, consumers should see this as a “tipping point,” she said.

“Last time abortion was illegal, we didn’t have the internet. Digital surveillance wasn’t a factor,” Caltrider said. “It is very much now. It’s time that we really start to consider that there are harms when our privacy is violated.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.