Column: A ransomware attack cost this entrepreneur a year of his life and almost wrecked his business

- Share via

When ransomware bandits struck his business last June, encrypting all his data and operational software and sending him a skull-and-crossbones image and an email address to learn the price he would have to pay to restore it all, Fran Finnegan thought it would take him weeks to restore everything to its pre-hack condition.

It took him more than a year.

Finnegan’s service, SEC Info, went back online July 18. The intervening year was one of brutal 12-hour days, seven days a week, and the expenditure of tens of thousands of dollars (and the loss of much more in subscriber payments while the site was down).

The amount of details I had to deal with was just excruciating....Because I lost everything.

— Fran Finnegan, SEC Info

He had to buy two new high-capacity computers, or servers, and wait for his vendor, Dell, to master a post-pandemic computer chip shortage.

Meanwhile, subscribers, who had been paying up to $180 a year for his service, were falling away.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Finnegan estimates that as many as half his subscribers may have canceled their accounts, leaving him with a six-figure loss in income over the year.

He expects most to return once they learn SEC Info is up and running, but the hackers destroyed his customer database, including email contacts and billing information, so he has to wait for them to proactively restore their accounts.

Getting SEC Info back online required Finnegan to painstakingly reconstruct software that he had written over the prior 25 years and reinstall a database of some 15.4 million corporate Securities and Exchange Commission filings dating back to 1993.

It was a truly heroic effort, and it was all in his hands. Finnegan labored under intense, self-imposed pressure to get his service up and running just as it was before the attack.

“The amount of details I had to deal with was just excruciating and very frustrating — I thought, ‘I did all this once before, and now I’ve got to do it all again.’ Because I lost everything.”

This is what happens when a malicious software attack turns a business owner’s life upside down.

At roughly the midpoint, a few days before Christmas, he experienced a stroke — a mild one manifested in a series of falls, but not any cognitive difficulties — that he attributes to the stress he was under.

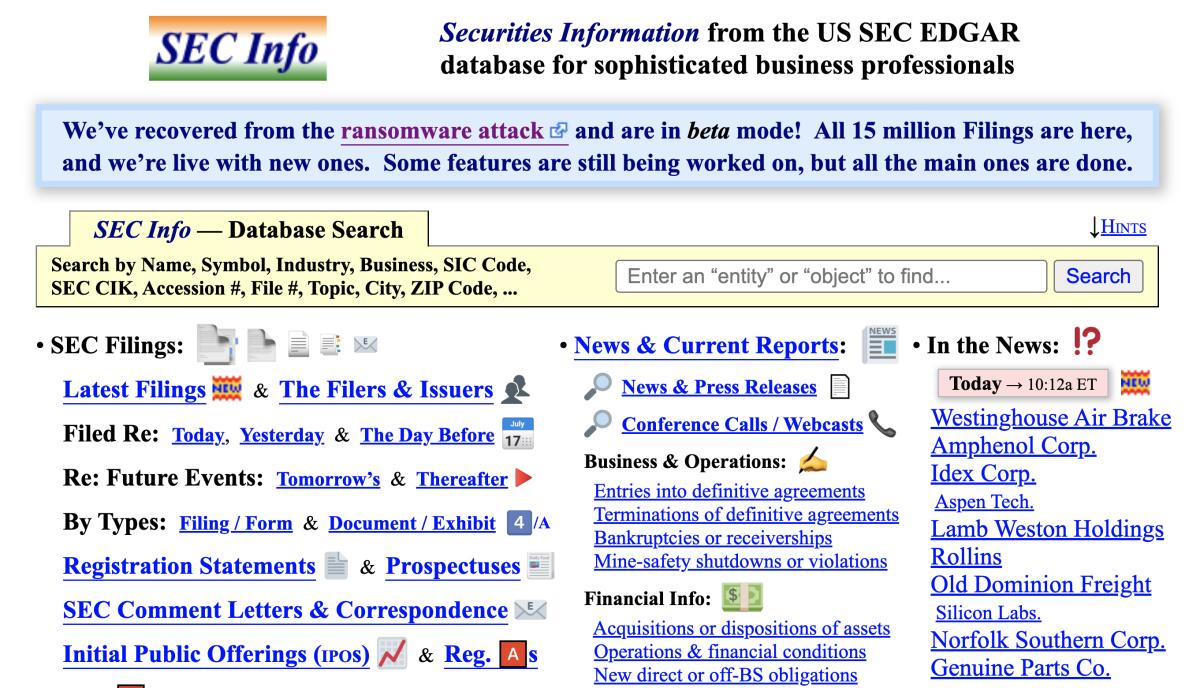

As I related last year at the start of Finnegan’s ordeal, SEC Info provides subscribers with access to every financial disclosure document filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission — annual and quarterly reports, proxy statements, disclosures of top shareholders and much more, a vast storehouse of publicly available financial information, presented in a searchable and uniquely well-organized format.

The website looks like the product of a team of data-crunching experts, but it’s a one-man shop. “This is my thing,” Finnegan, 71, told me. “I’m the only guy. Nothing happens unless I do it myself.”

With a degree in computer science and an MBA from the University of Chicago, as well as about a dozen years of Wall Street experience as an investment banker and a few years as an independent software designer for large corporations, Finnegan launched SEC Info in 1997.

The SEC had placed its EDGAR database online for free after recognizing that doing so would allow entrepreneurs to offer a host of innovative formats and related data services.

Finnegan was one of the pioneers in the field, eventually becoming one of the largest third-party vendors of SEC filings.

Finnegan’s experience opens a window into the consequences of ransomware that don’t get reported much — the impact on small businesses like his, which don’t have teams of data professionals to mobilize in response or a footprint large enough to get help from federal or international law enforcement agencies.

Ransomware attacks, in which perpetrators steal or encrypt victims’ online access or data and demand payment to regain access, have proliferated in recent years for several reasons.

One is the explosive growth of opportunity: More systems and devices are linked to cyberspace than ever before, and a relatively a small percentage are protected by effective cybersecurity precautions.

Data kidnappers can deploy an ever-expanding arsenal of off-the-shelf tools that “make launching ransomware attacks almost as simple as using an online auction site,” according to Palo Alto Networks, which markets cybersecurity systems. Some ransomware entrepreneurs “offer ‘startup kits’ and ‘support services’ to would-be cybercriminals, ... accelerating the speed with which attacks can be introduced and spread,” Palo Alto reports.

In late September, the website of journalist and cybersecurity expert Brian Krebs was hit with a crippling hacker assault known as a “distributed denial of service,” or DDoS, which knocked him off the Internet for several days.

The advent of cryptocurrencies may also have facilitated these attacks; perpetrators commonly demand payment in bitcoin or other virtual currencies, evidently on the assumption that those transactions are harder for authorities to track than those using dollars. (That may be a false assumption, as it turns out.)

It’s hard to put a finger on the scale of the ransomware threat, in part because most estimates come from private security firms, which may have incentives to maximize the problem and in any event offer varied figures.

What does seem clear is that the problem is growing, enough so that it has gotten the attention of the White House and international agencies.

Attacks on major enterprises garner the most attention. In 2021, according to a list of 87 attacks compiled by Heimdal Security, the victims included the business consulting firm Accenture, the audio company Bose, the Brazilian National Treasury, Cox Media, Howard University, Kia Motors, the National Rifle Assn. and the University of Miami.

Healthcare institutions have long been prime targets. Last year, Scripps Health, the nonprofit operator of five hospitals and 19 outpatient clinics in California, had to transfer stroke and heart attack patients from four hospitals and shut down trauma treatment centers at two.

Staff were locked out of some data systems. The attack cost Scripps at least $113 million, according to a preliminary estimate.

Finnegan’s attack was too small to show up on these rosters. But for him it was a life-changing event.

The catastrophe began with a massive data breach at Yahoo that happened in 2013 but which Yahoo didn’t disclose until 2016. The hackers stole the email passwords, phone numbers, birth dates and security questions and answers of 3 billion Yahoo users, including Finnegan.

Finnegan followed Yahoo’s advice to change the passwords on his Yahoo account but forgot that he had used the same password to access his administrative privileges at SEC Info.

Customers say Ring’s lousy security left them vulnerable to cyber-intruders.

That might not have been a problem, except that before leaving for a weeklong vacation last summer, he activated a digital access port so he could keep an eye on his system from afar.

His old password was a ticking time bomb in the hands of anyone with access to the stolen Yahoo data. Beginning last June 26, hackers pinged his system 2.5 million times with stolen Yahoo passwords, finally hitting on the right one.

“They lucked out,” he told me. “If they had tried a week earlier or a week later, they would not have been able to get in.”

Finnegan didn’t know his system had been hacked until a subscriber asked him by text message why his website was down. When he logged in remotely, he could only watch helplessly as the attackers encrypted all his files.

Finnegan thought he had been adequately backed up, as his data was stored on two servers, large-capacity computers housed at a data center in San Francisco. That was a safeguard against either server melting down but not against a hacker actually using his password.

He thought briefly about responding to the hackers, but a quick online search yielded reports from other victims reporting that they had paid the ransom without receiving a decrypt code.

Even if the hackers decrypted Finnegan’s data — the more than 15 million SEC filings — they had trashed his operational software, and that could not be recovered via decrypting.

So Finnegan set about reconstructing his system. Fortunately, about 90% of the filings had been stored on external discs at his Bay Area home, unplugged from the internet and thus out of the hackers’ reach.

But those were older filings from before 2020, the latest data on the stored discs. The remaining 10% had been destroyed — more than 1.5 million documents.

The unfolding showdown between Apple and the FBI is almost invariably depicted in terms of the security and privacy of your smartphone.

Downloading the more recent filings from the SEC took two months because the agency limits the pace of downloading from its database so that access can’t be monopolized by big users.

The harder task was reconstructing all the programs Finnegan had written over the years to parse the SEC data and make it usable for his subscribers in myriad ways.

“Some of this goes back 25 years, and you forget about stuff,” he told me.

At first, he says, “I thought I would just get the data, run it through the parsing engine again, and reconfigure everything and I’d be done.” He ran into a phenomenon memorably identified by former IBM software executive Fred Brooks in his classic book, “The Mythical Man-Month”: Software projects always take longer than anyone anticipates, and always miss their deadlines.

So weeks stretched into months. Finnegan would post a recovery date online and blow past it. “It got to the point where I stopped making predictions, because when it wouldn’t happen I felt like an idiot.”

By June, however, “I could see the end of the tunnel,” he says, and projected a return for his birthday, July 1. It still wasn’t ready, so he posted online a restoration date of July 15 — and finally went back up on July 18.

This time around, Finnegan has sealed the security holes that let his attackers run roughshod over his business. He receives data backups almost in real time and keeps them offline and unplugged from the internet and made the process of accessing his system remotely far more complex.

Finnegan still has a few tasks to complete to make SEC Info work exactly as it did before, but those involve functions that only a tiny minority of subscribers ever used. He’s confident that he won’t have to face this tribulation again.

“I’m pretty sure I’m not going to get hit again,” he told me. I heard a moment of doubt in his voice, but then his confidence returned. “No, no one’s going to get in again,” he said.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.