Column: Why is this foul-mouthed enemy of Social Security receiving a presidential honor?

- Share via

The 17 recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom named recently by the Biden White House are, by and large, distinguished Americans deserving of the nation’s highest civilian honor.

They include five social justice activists; leaders in the medical, labor technology and entertainment fields; and Olympic athletes.

As these things go, 16 out of 17 isn’t bad. But that 17th honoree — hoo boy, what a terrible blunder.

You do a total disservice to America with your organization.

— Presidential honoree Alan Simpson to a Social Security advocate, 2012

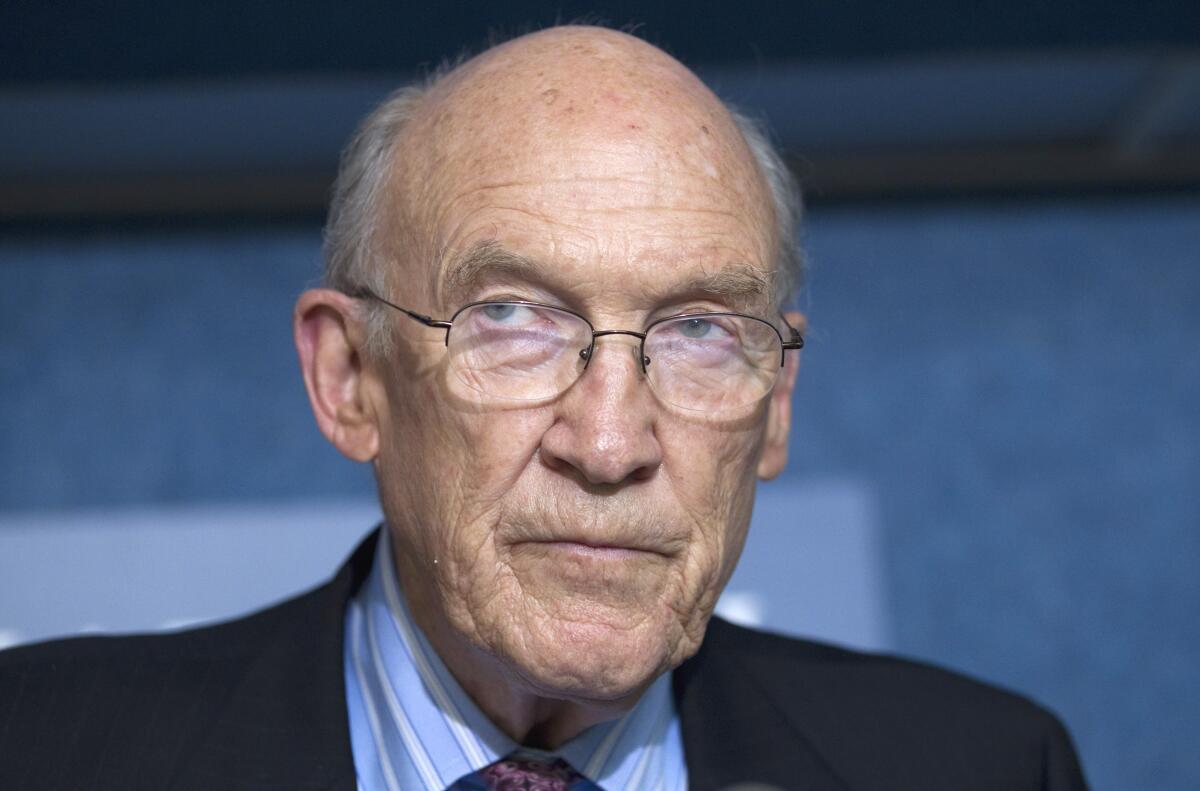

He’s former Sen. Alan Simpson, Republican of Wyoming. He is one of three ex-politicians on the list, the others being former Rep. Gabrielle Giffords (D-Ariz.), who, after being grievously wounded in a shooting in 2011, founded a nonprofit devoted to stamping out gun violence; and the late Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), a Vietnam War hero and GOP candidate for president in 2008.

Simpson, 90, isn’t worthy of carrying their luggage — not theirs, not anyone else’s on the list. In announcing the honor, Biden lauded Simpson for speaking up in favor of campaign reform and for marriage equality. He didn’t mention, however, Simpson’s long campaign to undermine Social Security benefits as the token Republican co-chair of an Obama-created commission on the federal deficit in 2010.

In that role, Simpson distinguished himself as a foul-mouthed, intemperate, obnoxious purveyor of misinformation about Social Security.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The commission’s inclination was to bring this all-important federal program into fiscal balance essentially by cutting benefits. As it happened, its proposals were unable to achieve sufficient support from the panel’s 18 members, so it disbanded, unlamented, before the end of 2010 without issuing any recommendations at all.

Simpson, however, continued to argue for benefit cuts for years. Remarkably, he never responded to the multiple critiques of his ideas with cogent rebuttals. Instead, he attacked his critics with name-calling of the most infantile, vulgar variety, and with transparent lies.

I tracked Simpson’s prevarications for years in print, eventually receiving a bilious email from him in which he simply repeated the lies I had debunked.

This was like a reflex with Simpson. He disdained recipients of Social Security as “greedy geezers.”

Alan Simpson is more wrong than ever on Social Security

(The average Social Security retirement benefit today is $19,455 a year, a couple of notches above the federal poverty line. My back-of-the-envelope calculation places Simpson’s congressional pension, for which he became eligible after retiring from the Senate in 1997, at about $87,000 a year.)

After the Oakland-based California Alliance for Retired Americans organized a protest at an appearance that Simpson made with his commission co-chair, Erskine Bowles, he called their positions “a nefarious bunch of crap” and “bulls—.”

In an email to Ashley Carson, then an official of the Older Women’s League who had upbraided Simpson in the Huffington Post, he compared Social Security to “a milk cow with 310 million tits.” He closed the email with a rudely dismissive sign-off: “Call when you get honest work.”

To Max Richtman, then as now the president and chief executive of the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare, he asserted, “You do a total disservice to America with your organization..., and you know damn well what we have to do to shore up Social Security but since you make money pretty good by juicing up the troops, you’re not about to buy a bit of it.” Richtman was right and Simpson was wrong, as usual.

Simpson plainly regarded himself as a truth-teller on Social Security and couldn’t bear it that people who actually knew something about the program were calling him out.

Unfortunately, the lies that Simpson retailed still walk among us, obstructing a reasoned debate about the program’s future. So it’s worthwhile to review them and reestablish the truth.

Simpson repeatedly argued that Social Security was never designed as a “retirement system.” He contended that the term “retirement” appeared nowhere in the congressional hearings on the bill, writing that he “reviewed the hearings … and never found the word ‘retirement’ in any of the early beginnings of the construction of Social Security.”

Alan Simpson opens his yap on Social Security

He challenged me, thus: “When you find the word ‘retirement’ in your vast research, either uttered by Labor Secretary Frances Perkins or Edwin Witte, head of the Committee on Economic Security, appointed by President Roosevelt in 1934, please share it with me.”

Too easy.

As I showed, the hearings were shot through with numerous references to Social Security as a “retirement” program by Perkins and Witte, in hearings before both the House Ways and Means and Senate Finance committees, as well as in the Committee on Economic Security’s report. (The transcripts and the report are available on the website of the Social Security Administration, if you wish to see for yourself.)

Perhaps Simpson’s most dishonest claim was that Social Security’s drafters deliberately set the retirement age at 65 because life expectancy in 1935, at the time of enactment, was 63.

In other words, Simpson claimed it was designed from inception to rip off working Americans. This is a slander of the social insurance advocates who created the program and the legislatures and president who enacted it into law, and it’s demonstrably untrue.

Simpson was misinterpreting life expectancy statistics and their bearing on Social Security. To set the record straight once again: In the 1930s, life expectancy at birth was about 63. But that’s an artifact of high infant mortality rates in that era, and completely irrelevant to the fiscal health or purpose of Social Security.

What’s more important is life expectancy at age 20, when Americans generally begin their working lives and start contributing to the program, and what’s even more important is life expectancy at 65, because that defines the length of one’s retirement and therefore one’s lifetime as a Social Security beneficiary.

Those who had reached age 20 in the 1930s had average life expectancies of nearly 69, according to government statistics, and those who were already 65 had an average life expectancy of nearly 78. Social Security’s architects knew this full well and designed the program to accommodate it.

This article was originally on a blog post platform and may be missing photos, graphics or links.

As Witte told Congress, “Whether a person works in a small establishment or a large establishment ... there is one common characteristic, which is that everybody grows old, and they all have to make provision for their old age or somebody has to take care of them. ... Whether you do it in the form of pensions, or in some other way, there is no way of escaping that cost.”

Simpson tried to justify cutting Social Security benefits by pointing out how the program had expanded since its original enactment in 1935. This is true but also irrelevant. The expansions, including the addition of disability coverage, were enacted by succeeding Congresses and presidents — most of them during the administration of Dwight D. Eisenhower, a Republican.

Honoring Simpson with a Presidential Medal of Freedom appears to reflect President Biden’s determination to reach across the partisan aisle, presumably to narrow the ideological divide in America. It’s not his only misstep on that score: A deal he apparently struck with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) to place a viciously antiabortion judge on the federal bench in Kentucky in return for Senate approval of two Democratic U.S. attorneys in Kentucky has predictably, and properly, infuriated Democrats.

But nothing can justify gifting Simpson with any honor at all. Simpson worked assiduously to undermine a program that is the cornerstone of Democratic policy and the most successful government program in American history. He did as much as any politician of his era to lower the standard of public discourse. He was never able to rebut the challenges made to his claims but filled the vacuum with invective.

If Simpson shows up at the White House on Thursday for the medal presentation ceremony, he will be standing with many real American heroes: Olympians Simone Biles and Megan Rapinoe; Giffords and Gold Star father Khizr Khan; New York critical care nurse Sandra Lindsay, an inspiring figure in the fight against COVID-19; civil rights campaigner Diane Nash, an associate of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.; and Denzel Washington. Three people will be honored posthumously — Steve Jobs, McCain and former AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka.

Next to them the cynicism and dishonesty of Alan Simpson will be placed in sharp contrast. That his record is treated as honorable, rather than hushed up and relegated to the trash bin of history, is a sour commentary on heroism and distinction in modern America.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.