Horrific allegations of racism prompt California lawsuit against Tesla

- Share via

Warning: This story quotes several racist slurs allegedly directed at Black workers at Tesla’s California plant, according to a lawsuit filed against the company.

The N-word and other racist slurs were hurled daily at Black workers at Tesla’s California plant, delivered not just by fellow employees but also by managers and supervisors.

For the record:

4:05 p.m. Feb. 12, 2022An earlier version of this article said that at least 167 racial and sexual harassment suits were filed against Tesla since 2006. At least 160 worker lawsuits were filed over various grievances, not just harassment.

8:31 a.m. Feb. 11, 2022An earlier version of this article stated that Tesla operates the only major nonunion auto plant in the U.S. Tesla is the only major American automaker to operate a nonunion plant in the U.S.

So says California’s civil rights agency in a lawsuit filed against the electric-vehicle maker in Alameda County Superior Court on Thursday on behalf of thousands of Black workers after a decade of complaints and a 32-month investigation.

Tesla segregated Black workers into separate areas that its employees referred to as “porch monkey stations,” “the dark side,” “the slave ship” and “the plantation,” the lawsuit alleges.

Only Black workers had to scrub floors on their hands and knees, and they were relegated to the Fremont, Calif., factory’s most difficult physical jobs, the suit states.

Graffiti — including “KKK,” “Go back to Africa,” the hangman’s noose, the Confederate Flag and “F-- [N-word]” — were carved into restroom walls, workplace benches and lunch tables and were slow to be erased, the lawsuit says.

Tesla responded to the lawsuit, filed by the Department of Fair Employment and Housing, with a blog post saying that the agency had investigated almost 50 discrimination complaints in the past without finding misconduct — an assertion the agency denied.

“A narrative spun by the DFEH and a handful of plaintiff firms to generate publicity is not factual proof,” the blog post said, adding that the company provides “the best paying jobs in the automotive industry … at a time when manufacturing jobs are leaving California.”

The lawsuit comes in the wake of Tesla’s billionaire chief executive, Elon Musk, moving the company’s headquarters from Palo Alto to Austin, Texas, where he is building a major new assembly plant.

The state’s lawsuit suggests the relocation to a state known for looser enforcement is no coincidence, declaring it to be “another move to avoid accountability.”

Not only were Tesla’s Black workers subjected to “willful, malicious” harassment, but they were also denied promotions and paid less than other workers for the same jobs, the suit asserted. They were disciplined for infractions for which other workers were not penalized.

In an interview, DFEH Director Kevin Kish said the lawsuit is the largest ever brought by the state for racial discrimination in terms of the size of the affected workforce since the agency gained prosecutorial powers in 2013.

Before that, complaints were handled by an agency administrative law judge rather than in court. But as more employers have forced workers to sign arbitration agreements preventing them from taking complaints to court, “government has the only effective enforcement mechanism to remedy broad pervasive violations in a workplace,” he said.

“We hear a lot about ‘structural racism.’ This case is very focused on segregation — the structural barriers to equality for Black employees,” Kish said.

Most of the agency’s complaints involve individual workers or small groups. And racial complaints are on the rise. In 2016, the agency investigated 744 cases. By 2020, that had grown to 1,548, Kish said.

The economic and political stakes of taking on Tesla are hard to exaggerate: The company has drawn praise for proving people will buy electric cars when most of the auto industry was saying that would be impossible.

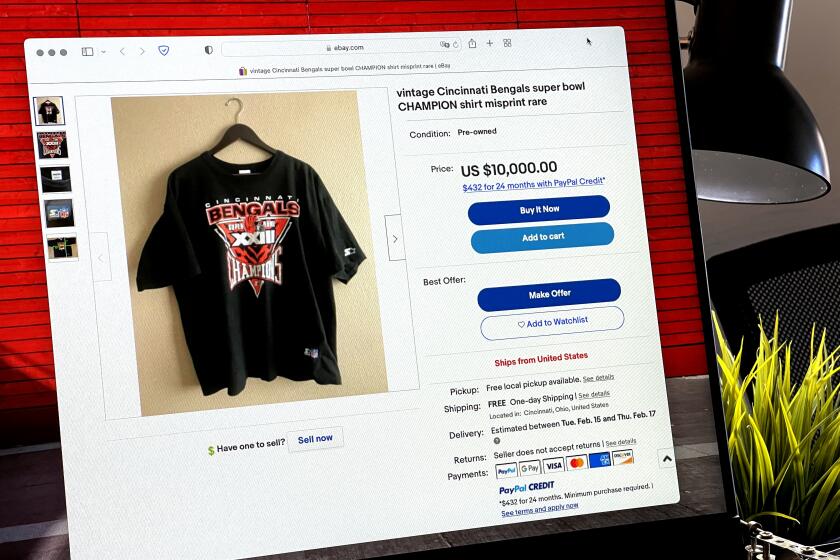

The bizarre economy of Super Bowl merchandise: What happens to the losing team’s ‘champion’ apparel?

Right now, thousands of caps, T-shirts, sweatshirts and face masks proclaiming the Los Angeles Rams the next Super Bowl champion are sitting in boxes. What happens if they lose?

Although competition is growing, it’s still the top-selling EV brand worldwide. In 2021, the company said, it delivered 936,172 cars, 87% more than in 2020.

“Tesla markets its vehicles to the environmentally- conscious, socially responsible consumer,” the lawsuit states. “Yet [that] masks the reality of a company that profits from an army of production workers, many of whom are people of color, working under egregious conditions.”

Tesla’s Fremont factory is the only nonunion plant in the U.S. operated by a major American automaker.

California’s crackdown on the carmaker, which has 36,200 employees in the state and 80,000 worldwide, has been a long time coming. Black workers’ complaints of racial harassment and discrimination at the Fremont plant, which employs 15,000, date from 2012, the agency said.

Black workers make up 20% of Tesla’s factory assemblers, but there are no Black executives and just 3% of professionals at the Fremont plant are Black, the lawsuit said.

In 2017, the California Civil Rights Law Group, a Bay Area firm, filed a class-action lawsuit against Tesla on behalf of 1,000 Black workers. It has interviewed more than 100 who make claims similar to those in this week’s DFEH lawsuit. But that private lawsuit, still in court, covered only workers employed by staffing agencies that did not make them sign arbitration agreements.

Like many companies now, Tesla requires its directly hired employees to sign arbitration agreements, relegating any complaints to secret proceedings with private judges and without any option to appeal. After the 2017 class-action suit, it also required its staffing agency workers to sign agreements waiving their rights to go to court.

Government agencies are not required to respect arbitration agreements, which opens the way for California’s broader lawsuit.

Lawrence Organ, the lead attorney in the 2017 suit, said his firm of six lawyers, which specializes in harassment cases, has seen a marked rise in race-related complaints in the last five years. Before that, his firm had handled just two or three such cases in a decade. Today, it has 30 pending cases involving the N-word.

“Ever since Trump started running for president in 2015, there has been this change in attitude by people who harbor racist thoughts and racist beliefs,” he said. “They think that they can speak out and say whatever they want to say.”

Besides the N-word, harassment at Tesla, according to the DFEH lawsuit, included slurs such as “Monkey toes,” “banana boy,” “hood rats” and “mayate,” a Spanish word for dung beetle.

But the Tesla cases are “very unusual,” Organ said, because “Tesla doesn’t enforce its alleged zero tolerance policy for racist conduct.” He added that he had sued the NUMMI auto plant, which occupied the same factory before Tesla, many times for employment cases “but never for racial harassment.”

At Tesla’s Fremont factory, Black workers’ complaints were “ignored or perfunctorily acknowledged and then dismissed” by management, the lawsuit alleges. Those who complained were subject to “retaliatory harassment, undesirable assignments and/or termination.”

Musk, who grew up in South Africa, responded to the 2017 class-action suit, which called the company “a hotbed of racist behavior,” with an email to employees describing company culture as “hardcore and demanding.” Anyone who makes an ”unintentional slur” should apologize, he wrote, and the recipient should “be thick-skinned and accept the apology.”

In October, a federal jury in San Francisco awarded a Black elevator operator at Tesla’s plant $137 million in a harassment case. A judge signaled in January the award may be reduced but did not grant Tesla’s request for a new trial.

At least 160 worker lawsuits have been filed against Tesla since 2006, according to Plainsite, a court document transparency organization. The last two years have seen a major uptick in racial and sexual harassment suits against Tesla. At least five have been filed in the last six weeks.

One was lodged by a female Black employee who said her female white boss struck her with a hot grinding tool and called her “stupid” and the N-word and insulted her intelligence. The suit says the supervisor was fired but later rehired.

Another was filed by a man who said he wrote directly to Musk to complain about racial harassment and was then told to report to human resources, where he was fired.

Tesla hired most workers through 14 staffing firms “to avoid responsibility,” the state lawsuit asserted. The carmaker declined to investigate complaints by staffing agency workers, although most of the Black workers were employed by staffing firms.

Staffing firms were also an issue in two large race discrimination cases brought by the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission involving hundreds of Black warehouse workers in the Inland Empire.

A Moreno Valley case against Ryder Integrated Logistics and its staffing firm, Irvine-based Kimco Staffing Services, charged that at least 121 Black workers were frequently subjected to the N-word and other slurs by fellow workers and managers, and exposed to racist graffiti in the restrooms. Assembly lines were segregated by race, with Black workers and Latino workers in separate work areas. The two companies failed to investigate and retaliated against workers who complained, the EEOC said.

The suit was settled in May for $2 million. The companies were required to create a tracking system for discrimination, revise its policies and submit to stringent outside monitoring.

A similar EEOC lawsuit in Ontario against Cardinal Health, the giant medical distribution company, and its Glendale-based staffing agency, AppleOne, was settled in July for $1.4 million and requirements for stringent policy and monitoring rules. The case involved frequent N-word harassment, graffiti and job discrimination affecting hundreds of Black workers.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.