Drilling for ‘white gold’ is happening right now at the Salton Sea

- Share via

Barely a mile from the southern shore of the Salton Sea — an accidental lake deep in the California desert, a place best known for dust and decay — a massive drill rig stands sentinel over some of the most closely watched ground in American energy.

There’s no oil or natural gas here, despite a cluster of Halliburton cement tanks and the hum of a generator slowly pushing a drill bit through thousands of feet of underground rock. Instead, an Australian company is preparing to tap a buried reservoir of salty, superheated water to produce renewable energy — and lithium, a crucial ingredient in electric car batteries.

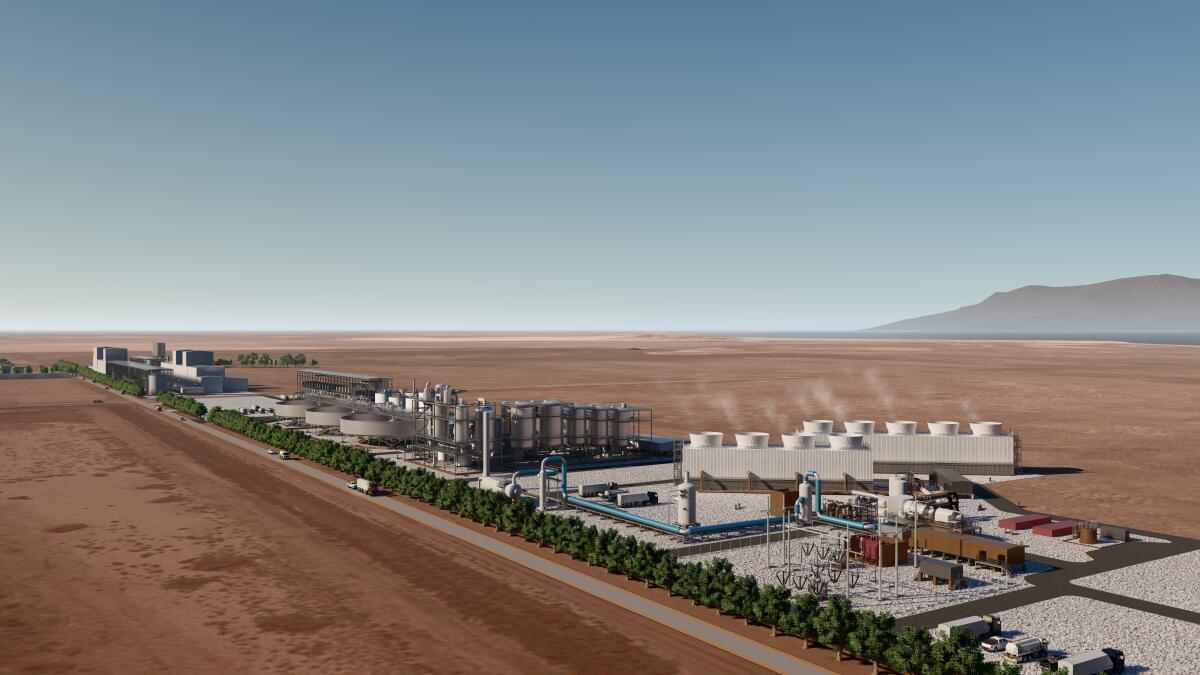

The $500-million project is finally getting started after years of hype and headlines about the Imperial Valley someday becoming a powerhouse in the fight against climate change. The developer, Controlled Thermal Resources, began drilling its first lithium and geothermal power production well this month, backed by millions of dollars from investors including General Motors.

If the “Hell’s Kitchen” project succeeds — still a big “if” — it will be just the second commercial lithium producer in the United States. It will also generate clean electricity around the clock, unlike solar and wind farms that depend on the weather and time of day.

“We know we can do it. Now it’s a matter of how well can we do it,” said Jim Turner, Controlled Thermal’s chief operating officer.

On a hot afternoon last week, hard-hatted workers crowded onto a platform next to the 170-foot derrick, using their hands to remove clumps of clay being coughed up from underground and threatening to slow the drill bit’s descent.

Other than that unexpected hitch, the operation was going smoothly. The drill had reached a depth of about 900 feet, on its way to a reservoir that seismic surveys showed would begin at about 4,000 feet, with temperatures of at least 600 degrees Fahrenheit.

The briny water is rich with lithium and other valuable minerals. Controlled Thermal is eager to reach that lucrative deposit.

“If we’re lucky, we’ll finish [drilling] before 40 days. But you don’t know until you actually get down there,” Turner said.

There are already 11 geothermal power plants in the area, churning out emissions-free energy for California and Arizona. They take advantage of a natural geothermal hot spot, where heat from the Earth’s core radiates outward and warms water trapped in underground rock formations.

Energy companies drill down and bring the superheated water to the surface, where the drop in pressure causes it to “flash” from a liquid to a gas, creating bursts of steam that can turn turbines and generate electricity.

At the end of the process, the brine is injected back underground, replenishing the reservoir. The main byproduct is water vapor.

The technology is expensive, and for years development had ground to a halt. But now California is swimming in cheap solar and wind power, and officials are scrambling for clean-energy resources that can be counted on 24/7, especially after sundown.

California’s first new geothermal plant in nearly a decade recently started construction in Mono County. The Imperial Irrigation District, meanwhile, has agreed to buy most of the 50 megawatts of power that Controlled Thermal would initially generate.

After years of playing third fiddle to solar and wind power, new geothermal plants are finally getting built.

Still, the Hell’s Kitchen project might not have reached this stage without booming demand for lithium-ion batteries.

General Motors plans to introduce 30 electric vehicle models by 2025 and to stop selling gasoline-fueled cars by 2035, in line with Gov. Gavin Newsom’s target for California. Ford expects to invest $22 billion in EVs over the next few years, including the all-electric F-150 Lightning pickup truck. Overall, Consumer Reports says nearly 100 battery-electric cars are set to debut by 2024.

As prices have fallen, batteries have also become popular among utility companies looking to balance out solar and wind power, and among homes looking for blackout insurance. There are already 60,000 residential batteries in California, and that number is expected to grow substantially as the electric grid is battered by more extreme fires and storms fueled by climate change.

Your guide to our clean energy future

Get our Boiling Point newsletter for the latest on the power sector, water wars and more — and what they mean for California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Those energy storage systems will require huge amounts of lithium. Industry data provider Benchmark Mineral Intelligence projects that demand for the metal — sometimes known as “white gold” — will grow from 429,000 tons this year to 2.37 million tons in 2030.

Today, most of the world’s lithium comes from destructive evaporation ponds in South America and hard-rock mines in Australia. Proposals for new lithium mines in the United States — including the Thacker Pass project on federal land in Nevada and plans for drilling just outside Death Valley National Park — face fierce opposition from conservationists and Native American tribes.

The Imperial Valley resource, by comparison, could offer vast new lithium supplies with few environmental drawbacks.

“It’s a whole new industry, it’s a whole new tax base, it’s a whole new sector,” Controlled Thermal Chief Executive Rod Colwell said.

Imperial Valley residents are wary of those kinds of promises, thanks to a long history of developers trying and failing to profit from minerals dissolved in the salty waters deep beneath the Salton Sea (which have no connection to the surface lake). Companies have typically been foiled either by poor economics or by the brine’s highly corrosive nature.

None of the busts was more dramatic than that of Simbol Materials. The secretive startup claimed to have developed a game-changing lithium extraction technology, catching Elon Musk’s attention and prompting Tesla to offer $325 million to buy the company in 2014, as later revealed by the Desert Sun newspaper. Simbol spurned the purchase offer and soon ran out of money.

But it’s now looking more likely that at least one company will solve the puzzle.

Controlled Thermal has teamed up with well-funded lithium extraction startup Lilac Solutions, whose backers include Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos. San Diego-based EnergySource, which operates the Salton Sea’s newest geothermal facility, developed its own extraction technique and expects to start construction on a lithium plant by April 1. Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Energy, which owns the rest of the region’s geothermal fleet, is working toward a lithium demonstration facility with state funding.

Simbol’s patents, meanwhile, are now controlled by a joint venture involving major oil producer Occidental Petroleum Corp.

Lithium is key to renewable energy, electric cars and cellphones. And there’s loads of it in the Imperial Valley.

Turner, for one, welcomes the competition. Even if Controlled Thermal succeeds in producing 20,000 tons of lithium hydroxide by 2024 — and eventually as much as 300,000 tons annually — he thinks there will be more than enough demand to go around.

“If all of us made all the lithium we could ever make out of here, it all would get sold into the automotive industry,” he said.

To be clear, Controlled Thermal still has obstacles to overcome.

Before the company can secure hundreds of millions of dollars in financing to start building a power plant, it will need a water supply agreement from the Imperial Irrigation District — always a thorny request in a valley whose massive Colorado River water rights are zealously guarded by landowning farmers. An environmental analysis from Imperial County is another prerequisite.

Perhaps most important, Controlled Thermal needs General Motors — or another party — to sign a formal agreement to buy the lithium that Hell’s Kitchen would produce. GM recently announced a multimillion-dollar investment in the Australian company, in a deal that gives the auto giant first dibs on the lithium. But that won’t be enough for Controlled Thermal to line up construction financing.

Still, the fact that Controlled Thermal is spending $5 million to drill its first production well — with another $5-million well to follow immediately afterward — bodes well for the company’s prospects. Turner pointed to GM’s investment as a vote of confidence.

“Believe me, GM did their homework,” he said.

The Imperial Valley has long been a land of dreamers.

White settlers looked across the harsh, dry landscape at the turn of the 20th century and saw an agricultural empire. They built that empire — which today comprises half a million acres of farm fields — despite an early incident in which the Colorado River overran an irrigation canal and flowed for two years into the low-lying Salton Sink, creating California’s largest lake.

The Salton Sea later became a postcard-perfect resort mecca frequented by Frank Sinatra.

It’s also a place where dreams go to die.

The resorts were abandoned after tropical storms and farm runoff caused the Salton Sea to flood.

Support our journalism

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times.

Later, the shoreline began to recede as farmers were pressured into selling water to coastal cities, exposing a lakebed covered in dust laced with agricultural pesticides and heavy metals. Fierce winds have increasingly blown that toxic dust into the air breathed by the Imperial Valley’s largely Latino, low-income population, fueling an asthma crisis.

Efforts to restore the Salton Sea’s fish and migratory bird habitat have consistently faltered.

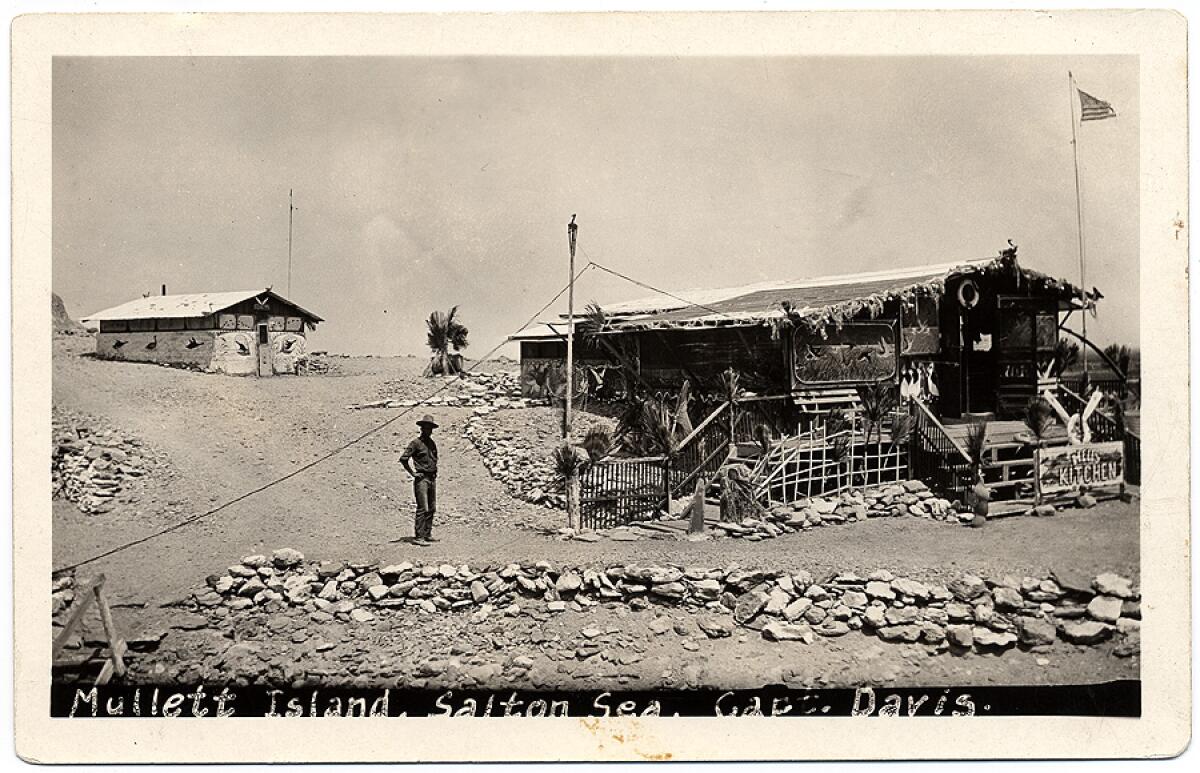

The Hell’s Kitchen project nods to that history, the good and the bad. It’s named for a restaurant and dance hall built by a colorful character known as Captain Charles Davis atop a dormant volcano called Mullet Island in 1908, just after the Salton Sea formed.

A century later, the island has become a peninsula as the water recedes. Only ruins of the long-gone restaurant remain.

Today’s energy companies hope to stick around longer than Captain Davis. With California aiming for 100% clean electricity and a carbon-neutral economy by 2045, they have good odds of turning their dreams into reality. Now they have to stick the landing.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.