Column: Tesla’s aggressiveness is endangering people, as well as the cause of good government

- Share via

With as many as 10 deaths under investigation by regulators, evidence of the hazards that Tesla drivers misusing their cars’ self-driving systems continues to emerge.

But there’s another, less-heralded danger posed by the Tesla-can-do-no-wrong fans. The victims here aren’t innocents sharing the road with Tesla drivers, but the causes of good government and sound safety regulations.

The Tesla claque has been in full cry online against the planned appointment to a key federal oversight position of one of the most effective and incisive critics of the obviously premature rollout of autonomous driving systems in Tesla cars.

We’re going to see more accidents happen. People are mentally checking out because they think the autonomy is more capable than it is.

— Missy Cummings

She’s Missy Cummings, an expert in autonomous technologies and artificial intelligence at Duke University. Cummings has been named senior adviser for safety at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Word of Cummings’ appointment produced an uproar among Tesla fans on Twitter that was so obnoxious and obscenely misogynistic that Cummings had to delete her Twitter account. (Warning: Linked tweet is not safe for work — in fact, not all that safe even for mature adults.)

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

A petition on Change.org calling for Cummings’ appointment to be reversed has accumulated more than 26,000 signatures. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg felt compelled to defend the Cummings appointment at a press conference. But he stood by it.

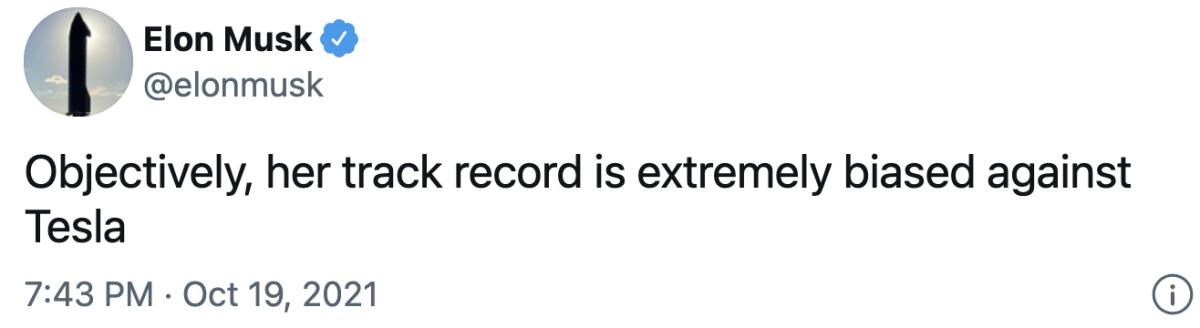

Tesla CEO Elon Musk, whose every uttered thought is slavishly followed by his fan base, could have shut down this contemptible uproar. Instead, he fed it by referencing Cummings in a tweet, stating: “Objectively, her track record is extremely biased against Tesla.”

A couple of points about that. First, Elon Musk is absolutely incapable of being objective about anything related to Tesla.

Second, Cummings is perhaps our most articulate critic of self-driving hype. She has been uncompromising in her criticism of Tesla for its approach to self-driving technology and its exaggerations of its capabilities, but her criticism extends to promoters of autonomous driving technology generally.

“I’ve been on this one-man, Don Quixote-esque attempt to warn people about the real immaturity of artificial intelligence in self-driving systems,” she told technology podcaster Ira Pastor in May.

Elon Musk complains about California’s regulations — but they’ve put billions of dollars in his pocket.

As Cummings recounted, she and other experts in AI and human-machine interactions have been “trying to warn the self-driving and driver-assist communities for a while that these problems were going to be serious. We were all summarily ignored, and now people are starting to die.”

The fundamental problem, she said, is that “people are mentally checking out because they think the autonomy is more capable than it is... Until we can get some industry agreed-upon self-generated standards, we should turn these systems off” or allow them to be used only in environments for which they have been specifically designed — limited-access thoroughfares such as freeways.

She’s certainly right about that. For years, promoters of self-driving systems, including Musk, have defined the challenge of autonomous vehicles largely as one of developing sensor technologies that could discern obstacles, follow pavement and roadside markings, and avoid pedestrians. They’ve regarded the issue of human interaction with these systems as one of secondary importance, or even no importance at all.

To experts such as Cummings, however, it’s paramount. That’s not only because even in a “fully” autonomous vehicle — which doesn’t really exist yet in real life — human passengers will be more than just cargo, but will have to participate in navigation at some level. It’s also because until the nirvana of total autonomy arrives, humans will inevitably overestimate the systems’ qualities.

“We’re going to see more accidents happen,” Cummings told Pastor.

Here’s a quiz you can take at home: When will driverless cars become common on America’s highways?

The evidence of the mismatch between expectation and reality is brimming over online, where Tesla drivers have been posting blood-curdling videos of their cars’ performance under the company’s Autopilot and Full Self Driving, or FSD, systems. Teslas veer into incoming traffic, come within a hair of rear-ending parked cars, menace pedestrians crossing the street in front of them, barrel past stop signs.

These videos should strike all pedestrians or motorists seeing a Tesla coming down the road with terror. Musk has consistently maintained that Tesla’s self-driving systems are safe, but a critical mass of data doesn’t exist to validate that opinion. He also tweeted a threat that any Autopilot tester who isn’t “super careful” would get “booted.”

Instead, Tesla has effectively outsourced the testing of its self-driving systems to random Tesla drivers, who are airing them out on crowded city streets. This isn’t like Apple or Microsoft rolling out beta versions of their software for early-adopting users to debug on their own time; a failure of that technology usually can only harm the user. A failure of Autopilot, however, can kill people.

Yet as my colleague Russ Mitchell has reported, “little action has been taken by federal safety officials and none at all by the California Department of Motor Vehicles, which has allowed Tesla to test its autonomous technology on public roads without requiring that it conform to the rules that dozens of other autonomous tech companies are following.”

Most companies’ self-driving or driver-assist systems are designed to verify that drivers are behind the wheel and engaged in the cars’ operations — they use sensors to detect a body’s weight on the driver’s seat and hands on the wheel. Some use cameras to track drivers’ eye movements to determine whether they’re paying attention to the road.

Tesla’s systems have been criticized as too easy to trick, as Consumer Reports documented earlier this year. Social media also feature not a few videos of Teslas carrying passengers in the rear seat and not a soul behind the wheel.

The self-driving car era, such as it is, has not gotten off to an auspicious start.

It should be obvious that the California DMV — in fact, all state DMVs — should shut down Tesla’s implementation of self-driving technology on public streets and highways unless and until it reports results from controlled testing on closed roads.

The growing record of crashes involving Teslas with Autopilot engaged prompted NHTSA to launch an investigation in August. The agency said it had identified 11 crashes since January 2018 in which Autopiloted Teslas struck emergency vehicles parked at accident scenes. Seventeen persons were injured and one was killed, the agency said. Three of the incidents occurred in California.

The agency’s investigative notice observed that Autopilot gives the driver primary responsibility for identifying road obstacles or maneuvers by nearby vehicles that could collide with a Tesla on Autopilot. But it said it would look into how Tesla’s systems “monitor, assist, and enforce” drivers’ control.

Tesla’s promotion of its self-driving features as “Full Self Driving” has been a consistent concern of NHTSA and the National Transportation Safety Board, which Tesla has been stiff-arming over safety concerns for four years, as NTSB Chair Jennifer Homendy said on CNBC this week.

During that interview, a CNBC reporter noted that Tesla has explicitly informed drivers that they need to stay vigilant behind the wheel even when Autopilot is engaged.

“Are they not doing enough?” he asked Homendy.

She replied crisply, “No, that’s not enough.... It’s clear that if you’re marketing something as full self-driving and it’s not full self driving and people are misusing the vehicles and the technology, that you have a design flaw and you have to prevent that misuse.” Part of the issue, she said, is “how you talk about that technology.” Tesla’s description of its technology as “full self-driving,” she said, “is misleading.”

The signs are rife that self-driving automotive technology is simply not ready for prime time — and in some environments, such as city or suburban streets, not ready for any time. Navigating on roads where any other moving vehicles are under human control presents so many complexities and unpredictable eventualities that it may never lend itself to machine intelligence.

That’s an aspect that the champions of autonomous driving technologies have never fully come to grips with, despite the warnings of experts such as Missy Cummings. The public should be cheered that she’s now going to be in place to devote her expertise to making policy and, it is hoped, enforcing it.

Cummings has had praise for some things that Musk and Tesla have accomplished, especially a business plan that circumvents auto dealers. But she knows where to draw the line on self-driving claims, and it’s well short of where Musk draws it.

CNN host Michael Smerconish mentioned to Cummings during an interview this year, “Elon Musk has been quoted as saying that we’re safer with machines than we are with humans... What’s your answer?”

“I would say that’s true for some machines, but not his machines,” she replied. “There’s still a huge gulf that we’ve got to get across before his machines are anything close to safer than a typical human driver.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.