Should California ban gas in new homes? A climate battle heats up

- Share via

Tim Kohut’s job is to build homes that are affordable and use energy efficiently. Lately, he’s decided the best way to do that is to create communities that are powered solely by electricity, with no natural gas hookups.

As director of sustainable design for National Community Renaissance, one of the nation’s largest nonprofit affordable housing developers, Kohut helped plan a recently opened senior community in Rancho Cucamonga that produces as much electricity as it uses, thanks to solar panels spread across rooftops and carports. The home builder went a step further with a development under construction in Ontario, designing homes with electric heating and cooking. Natural gas will be used only for clothes dryers.

Next up are housing projects in San Bernardino, San Pedro and Santa Ana, and these will be all-electric.

With electric appliances getting cheaper, Kohut is convinced that ditching gas entirely is the best way to keep housing prices and utility costs low — not to mention reduce the carbon emissions fueling the climate crisis.

“I don’t win any arguments by saying we have to do this because of environmentalism,” he said. “I have to make the dollar and cents argument.”

Kohut’s experience could become the norm for home builders in California. The question is how soon.

Record heat. Raging fires. What are the solutions?

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter about climate change, the environment and building a more sustainable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

As the California Energy Commission crafts its next update to building regulations, climate activists are urging the agency to ban gas hookups in new construction. Another influential agency, the California Air Resources Board, voted last month to support all-electric building policies, based on research showing that indoor air pollution spewed by stoves and other gas appliances can contribute to health problems, including asthma and heart disease.

Californians were reminded of the urgency of climate action in recent months by a record-breaking spate of fires, made worse by rising global temperatures. Fires have burned 4.2 million acres and killed 31 people so far this year.

As the flames devoured homes and forests, Gov. Gavin Newsom promised “giant leaps forward” on fighting climate change.

“While we’re leading the nation in low-carbon green growth, as we’ve led the nation in our efforts to decarbonize our economy, we’re going to have to do more, and we’re going to have to fast-track our efforts,” the governor said in September.

Newsom’s office declined to say whether the governor will weigh in on gas hookups in new homes.

With or without the governor’s involvement, the battle over the fossil fuel is heating up. Forty cities and counties have prohibited or discouraged gas hookups in new construction over the last year and a half, according to a Sierra Club list. Oakland joined the ranks last week with a ban on gas in new housing, the same day San Jose expanded its existing ban.

The spread of those policies has prompted sharp pushback from the gas industry, led by Southern California Gas Co., the nation’s largest gas utility. Other critics include gas utility workers and the California Restaurant Assn.

“What happens if I want to build a home with natural gas, and I’m told I cannot?” asked Richard Meyer, managing director of energy analysis at the American Gas Assn., an industry trade group that counts SoCalGas as a member. “What happens when I reply that it’s the fuel my family has always cooked with, and it’s a lot less expensive for me to use?”

The rest of the country is paying attention.

With gas industry prodding, lawmakers in Arizona, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Tennessee approved bills this year prohibiting local governments from banning gas. The battle could intensify under soon-to-be President Joe Biden, whose climate plan includes rebates and low-cost financing to help families install electric appliances.

At least so far, the California Energy Commission hasn’t given any sign it will include the all-electric requirement sought by activists in its next building code update, which is set to be finalized in July 2021 and take effect in January 2023.

Commission staff are still writing the new rules, with a draft expected early next year. But a coalition of building industry groups suggested in a recent letter that the agency previously agreed not to mandate all-electric homes or make other major changes this code cycle, in exchange for home builders supporting a solar mandate last time around.

Bob Raymer, senior engineer at the California Building Industry Assn., said the handshake deal was designed to give home builders time to “climb the Mt. Everest” of the solar mandate, which required solar panels on new houses starting in 2020. He said many builders haven’t designed all-electric homes and need time to get comfortable with technologies such as high-efficiency electric heat pumps.

He also noted that consumers typically say they prefer gas stoves, although many haven’t tried modern induction cooktops that proponents say are far superior than electric coil ranges.

Curtis Stone has been using induction cooktops for years.

Raymer expects state officials to prohibit gas hookups — but not until the next code update, which will take effect in 2026.

“It’s just a question of how soon can we get this done competently, and not have a very disruptive transition,” he said.

Raymer worries that moving too quickly could further slow California’s housing market, which already doesn’t produce enough homes to keep up with demand. A lack of housing has helped drive skyrocketing prices and a persistent homelessness crisis.

“I shudder to think what we’re going to look like in three to four years if things don’t get better,” Raymer said.

Most new homes built in the United States in recent years don’t have gas hookups. The U.S. Census Bureau reported last year that more than half of homes built from 2010 to 2017 use electricity for space heating, water heating, cooking and clothes drying.

But in California, the vast majority of homes being built today are dual-fuel, meaning they’re connected to both the gas and electric grids. The state added 570,000 residential gas customers from 2010 to 2019, federal data show, more than any other state.

Gas burned in homes and businesses accounts for about 10% of the state’s planet-warming emissions, according to the Air Resources Board. An additional 15% can be traced to power plants that generate electricity used in homes and businesses.

Those power plant emissions should eventually fade away, at least in theory, because California law requires a 100% carbon-free electricity supply by 2045. But there’s no statewide plan for zeroing out emissions from gas-burning appliances in buildings.

Climate activists see the next energy code update as an opportunity for big progress. By requiring developers to build all-electric homes, they say, the Energy Commission can begin to shift the housing stock away from gas and grow the market for electric heat pumps and induction cooktops, driving down costs and prompting installers to get familiar with those appliances.

Support our journalism

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times.

Waiting until 2026 to ban gas hookups would result in an additional 3 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions and more than $1 billion spent on new gas connections, according to an analysis by the Rocky Mountain Institute, a think tank in Colorado.

“New housing construction is a relatively small piece of the puzzle,” said Denise Grab, a manager on the institute’s building electrification team. “But for every house we build out, for every gas line we extend, we’re digging more in the wrong direction. When you’re in a hole, you stop digging.”

Andrew McAllister, the California Energy Commission member overseeing the building code update, said the coming changes will probably encourage more developers to go all-electric by ratcheting up efficiency requirements. But he said it’s not clear whether the agency has the legal authority to ban gas entirely — at least not until buying and operating electric appliances gets cheaper — because state law requires energy-efficiency regulations to be cost-effective.

Like Raymer, McAllister cautioned against trying to move the market too quickly. He pointed out that Newsom recently set a 2035 deadline for ending the sale of gasoline-powered cars. Electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids made up 7.6% of new car registrations in the state last year, whereas electric heat pump water heaters had a market share of less than 2%.

“We have the nation’s most aggressive decarbonizing building code already,” McAllister said. “The question isn’t whether we have to get to zero-emission buildings. The question is what the path looks like.”

The costs of all-electric housing vary depending on the type of home and the appliances being installed. Building industry groups told state officials there’s usually no “significant difference” in cost between building an all-electric and a dual-fuel home, although they warned that Central Valley residents “should expect to pay $250 more per year to operate an all-electric home.”

Gas ban advocates disagree, offering their own data showing that all-electric homes can be cheaper to build and operate.

Kohut, from National Community Renaissance, is convinced that builders not embracing all-electric construction haven’t done their homework.

“If we can do this with affordable housing budgets, everybody should be able to do this,” he said.

UCLA researchers published a study last month concluding that Californians would probably pay more for energy under electrification mandates, and that “low-income residents of disadvantaged communities ... will be most adversely affected.” They also concluded that phasing out gas appliances could cause electricity use to rise dramatically in the evenings, when California has already had trouble keeping the lights on, as evidenced by brief rolling blackouts this summer.

But the study didn’t argue against electrification policies. Rather, it called for financial incentives to help low-income households buy electric appliances and for strategies to help avoid skyrocketing evening electricity demand.

“We believe in electrification,” said Eric Fournier, research director at UCLA’s California Center for Sustainable Communities and the study’s lead author. “We just want to make sure there are no surprises, particularly when you’re pitching it to low-income communities where they’re spending a large proportion of their income on energy.”

“It’s a no-brainer to require electrification of new construction projects,” he added.

Those nuances didn’t stop Frank Maisano — a media specialist at the government relations firm Bracewell who works with SoCalGas and other energy industry clients — from saying the UCLA study found that gas bans “disproportionately harm minorities/poor communities.” It’s an increasingly common line of argument from the fossil fuel industry, which has tried to stave off ambitious climate policies by casting itself as an ally of people of color.

The climate crisis disproportionately harms Black people, Latinos and Native Americans. But oil and gas supporters are trying to claim the moral high ground.

There’s growing support for phasing out gas appliances among environmental justice activists, who advocate for cleaner air and healthier environments in low-income communities of color.

Martha Dina Argüello, executive director of Physicians for Social Responsibility-Los Angeles, told the Air Resources Board last month that policymakers should work with disadvantaged communities to ensure that electric building requirements don’t drive gentrification or increase energy costs for those who can least afford it.

“We’re also looking at it as an opportunity to create new jobs and new economic opportunities,” she said. “We look forward to working with you so that we can actually create healthy communities where our lungs are beloved and cared for.”

A variety of businesses have also weighed in on the future of gas in homes.

The sustainability nonprofit Ceres sent a letter to state officials last week on behalf of a coalition of businesses that advocate for climate policies, including Ikea, McDonald’s, Nike and Starbucks. The letter called for an all-electric building code, saying quick action is “critical to maximizing progress in the building sector and avoid locking-in carbon-intensive buildings for decades.”

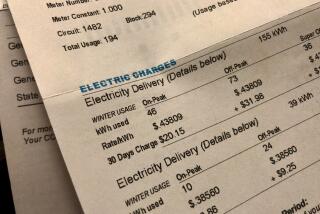

Two dozen companies that sell gas fireplaces submitted letters opposing an all-electric mandate. So did the Western Propane Gas Assn., which said Californians would face higher energy bills because electricity rates are higher than gas rates.

“An increase to utility bills is an increase to housing costs. A deeply irresponsible action to take as California faces the combined threats of insurmountable homelessness, and an unprecedented pandemic,” the propane association wrote.

Even before Berkeley approved the state’s first gas ban, SoCalGas started asking local governments to support “balanced energy solutions” — a key talking point in the utility’s campaign against electrification policies. A resolution originally drafted by SoCalGas has now been approved by 114 cities and counties, along with 20 school and water districts, according to a gas company list.

That’s more than three times as many local governments as have voted to support all-electric buildings.

“Implementing a balanced energy approach allows California to minimize disruption, manage cost and preserve consumer choice,” SoCalGas said in a report earlier this year.

Southern California Gas is engaged in a wide-ranging campaign to preserve the role of its pipelines in powering society.

Still, not every local government that’s been asked to support the gas company’s cause has said yes.

Redondo Beach’s City Council voted down the “balanced energy” resolution by a 4-1 margin in October. Councilman Christian Horvath warned that SoCalGas would use the city’s support to bolster its campaign to preserve gas, despite the company’s insistence that the resolution is not anti-electrification and doesn’t call out any one energy source for support or opposition.

“I think a lot of cities have been snookered by this,” Horvath said.

More to Read

Your guide to our clean energy future

Get our Boiling Point newsletter for the latest on the power sector, water wars and more — and what they mean for California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.