Column: Nasdaq steps into 21st century by requiring women and minorities on corporate boards

- Share via

Nasdaq has just put its money where its mouth is by proposing to require its listed companies to have at least two “diverse” directors, including at least one woman and one minority or LGBTQ director, or face being kicked off the exchange.

What’s most interesting about the proposal, which was submitted Tuesday to the Securities and Exchange Commission, isn’t that it’s radical in its reach.

It’s that the proposal recognizes the emerging reality in American industry, which is that resistance to diversity has been evaporating for years.

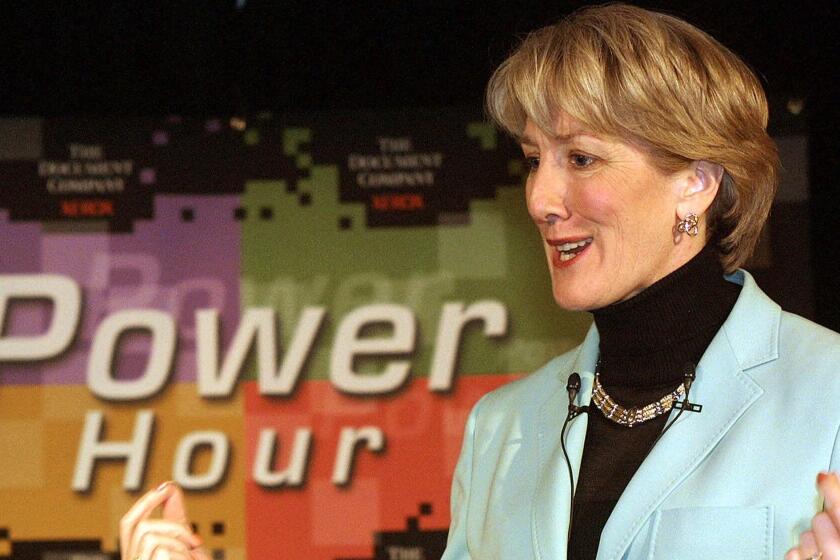

Nasdaq’s purpose is to champion inclusive growth and prosperity to power stronger economies.

— Nasdaq CEO Adena Friedman

Large consumer and technology companies have been among the leaders in the trend. CNN calculates that four of the five largest companies on Nasdaq, measured by market value, “have boards on which straight white men are in the minority.” They are Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet (the parent of Google) and Facebook.

Those companies plainly recognize that diverse boards are good for their bottom line, for their public image and for their standing in the investment community. In its proposal, Nasdaq observed that most large institutional investors have been pressuring corporate managements for more diverse boards.

Goldman Sachs, one of the leading underwriters of corporate stock offerings, said in January that it won’t take a company public unless it has at least one woman or minority director. By 2021, the minimum will be two directors.

And California has imposed mandatory diversity standards on companies headquartered within its borders. The state has required public companies based in the state to have at least one female director as of the end of last year and as many as three by the end of 2021.

A new law signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom this year requires those companies to have at least one minority or LGBTQ director by the end of 2021 and as many as three by the end of 2022.

Column: Last year CEOs pledged to serve stakeholders, not shareholders. You were right not to buy it

In the year since the CEOs promised to serve more than just shareholders, there have been few if any no signs that major corporations have taken real any steps they wouldn’t have taken without outside pressure, whether from public opinion or government regulation.

No other states have followed suit, possibly because they’re waiting for the outcomes of at least two lawsuits challenging California’s gender diversity law. But there are indications that the law has spurred California-based companies to step up their recruitment of female directors.

With state regulations vulnerable to legal challenge and with plenty of underwriters available for corporations unwilling to meet the standards of Goldman Sachs, “the exchanges really are ground zero for any meaningful governance initiatives,” says Nell Minow, an advocate for shareholder rights and improved corporate governance.

Minow calls the Nasdaq proposal “a very small step forward—almost infinitesimal—but a good one and exactly what they should be doing.”

Nasdaq’s proposal would give most of its listed companies one year to make public disclosure of its board diversity statistics, and another year to place at least one diverse director on their board.

Nasdaq cited academic studies finding that gender-diverse boards are associated with lower likelihood of manipulated earnings or other corporate wrongdoing, including securities fraud.

Some of corporate America certainly seems to have moved past its traditional resistance to diversifying the boardroom.

That attitude was exemplified by T.J. Rodgers, the founder and then-chairman of Cypress Semiconductor, who in a famous 1996 missive rebuffed one Sister Doris Gormley, a shareholder advocate at a Franciscan order in Pennsylvania, who told him the diversity of Cypress’ all-male board had been found wanting.

Rodgers, whose stubbornness was legendary, told the nun to “get down from your moral high horse.” Cypress depended on its directors to contribute expertise in semiconductors and experience in top management, criteria that usually yielded a 50-plus male with an advanced engineering degree, he wrote.

Here’s a surprising counterfactual to the oft-voiced concerns that American corporate boards are too heavily stocked with males: In recent years, major companies have actually been recruiting many more women than men as directors.

Cypress has since been acquired by Infineon, a German tech firm whose 16-member supervisory board includes seven women, in accordance with European standards.

That’s not to say that a kick in the pants isn’t warranted. A study published in September by the proxy advisory firm Institutional Shareholder Services found that progress in adding minority directors to the boards of Standard & Poor’s 500 companies was “glacial” relative to progress in adding female directors.

Women accounted for 27.4% of all S&P 500 company directors, ISS found, an increase of more than nine percentage points since 2015. But only 16.8% of directors were from underrepresented racial or ethnic backgrounds, a gain of only 3.2 percentage points over the same period.

ISS and Glass, Lewis & Co., the other major advisory firm, both said they would counsel their clients — large institutional investors — to vote against some board members at companies without any women on their boards.

Nasdaq’s proposal is an important step forward because, unlike state legislatures or proxy advisory firms, it can put teeth into its standard. The threat of delisting is a dire one for most public companies, which need their shares to be traded in a liquid market.

In the U.S., the only significant alternative is the New York Stock Exchange, which has taken a typically cautious approach to board diversity among its listed companies.

The Big Board last year set up a 20-member “advisory council” charged with “connecting diverse candidates with companies seeking new directors.” That’s pretty thin gruel compared with the Nasdaq initiative, suggesting that the exchange may have to fall into line now that Nasdaq has set the pace. The idea that NYSE-listed companies need networking help to fill board seats with women or minorities is absurd.

“We’re not that hard to find,” Minow says.

The Nasdaq rule will be subject to SEC approval, following a public comment period that will push a final decision well into next year. By then the SEC is likely to be remade by the Biden administration, perhaps into a more diversity-friendly body than it has been under Trump.

The single most pernicious idea in modern American finance is that the corporation exists to “maximize shareholder wealth.”

“Nasdaq’s purpose is to champion inclusive growth and prosperity to power stronger economies,” Nasdaq Chief Executive Adena Friedman said in announcing the proposal, calling it “one step in a broader journey to achieve inclusive representation across corporate America.”

California’s gender rule, which has been in effect for less than a year, seems to have worked. The law imposes a first-year penalty of $100,000 for every noncompliant board seat, rising to $300,000 for subsequent violations. The law applies to companies headquartered or incorporated in the state.

Since the law was passed in 2018, about 45% of new board appointments at covered companies within the Russell 3000 universe of public companies have been women, compared with 31% nationwide, according to Bloomberg.

According to a survey by the data firm Equilar cited by the Wall Street Journal, 93 California-based firms in the Russell 3000 had all-male boards when the gender law was signed in September 2018. As of this November, the number was 17.

The law has been challenged on equal-protection and state constitutional grounds. A federal judge threw out a lawsuit filed by a conservative legal foundation asserting that the requirement prevented a shareholder from voting as he wished, but the ruling is under appeal. A second lawsuit in state court, asserting that the gender quota is unconstitutional, is pending.

Legal authorities say the law could also be vulnerable under the “internal affairs doctrine” in federal law holding that the affairs of a corporation should be governed by the laws of the state in which it’s incorporated, which is often different from the state where it’s headquartered and for public companies seldom is California.

That said, no public companies have yet stepped up to challenge the California law directly. Possibly they realize that challenging a diversity rule that they could just as easily meet, to their own advantage, wouldn’t be a good look.

That’s the important context for the Nasdaq proposal. It’s a step forward in a direction that American business has been moving toward on its own. But an extra push can’t hurt a good cause.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.