Column: 23,000 households reported income over $10 million last year. The IRS audited seven

- Share via

Since we’ll be spending the next day or so pondering America as it is and as we wish it to be, let’s take a moment to contemplate how tax avoidance and evasion have become facts of life for some of the richest Americans.

They’ve done so with the connivance of our lawmakers, who have tied the hands of the Internal Revenue Service. The latest analysis of the situation came to us last week from David Cay Johnston, a journalist who has made the inequities of the income tax into a personal cause.

Johnston’s source material is official IRS statistics, so let’s delve into the facts alongside him.

IRS research studies from decades ago noted that at that time, the IRS pursued most nonfiler leads. However...that no longer appears to be the case.

— Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration

Here’s the most eye-opening statistic. Some 23,456 U.S. households reported income of $10 million or more last year (that is, for the 2018 tax year), averaging more than $26 million each in taxable income. The IRS audited seven of them.

That comes to less than three-hundredths of a percent. That’s about the chance of being struck by lightning at some point in your lifetime. So it may not be surprising that wealthy taxpayers don’t think they’re living dangerously with the IRS.

As it happens, however, America’s lowest-income households have much more to fear from the tax collector. Those with taxable income below $25,000 were audited at nearly 10 times the rate of the richest households, even though their average taxable income came to about $11,000 each.

Targeting low-income taxpayers won’t do much to close the so-called tax gap — the difference between what the government expects to collect in taxes and what it does collect. The IRS has estimated the gap at about $441 billion a year in tax years 2011 through 2013.

The college admissions scandal was hiding in plain sight for years.

But underpayment on this scale is more than a fiscal issue. It has a corrosive effect on trust in government broadly and the general public’s willingness to comply with tax law more specifically.

Revelations about President Trump’s years of tax shenanigans provide a model for the benefits of skipping out on one’s obligations, or the lack of consequences thereof.

It’s a rule of thumb in the tax world that almost no activity is as cost-effective at securing revenue as enforcing the tax law — or as detested by tax-avoiders. It’s hardly surprising, then, that tax cheating has soared as the IRS’ capacity to ferret it out has shrunk.

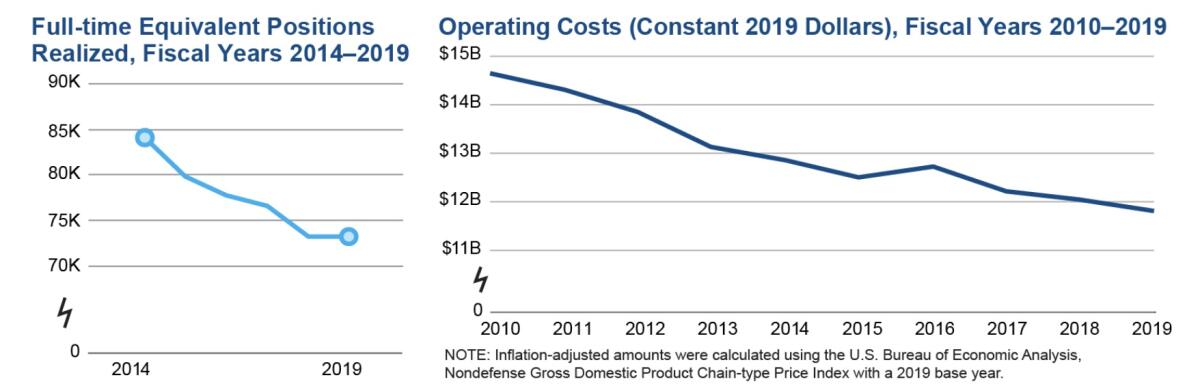

Congress and a succession of White House administrations — on both sides of the aisle — have systematically gutted the auditing and enforcement capabilities of the IRS. In 2010, the agency had 94,700 full-time staff and a budget of $14.7 billion. By the last fiscal year it was down to 73,554 full-timers and a budget of only $11.8 billion.

This shrinkage occurred as the agency’s workload was increasing inexorably. At the most fundamental level, as the U.S. population grew to 329 million last year from 251 million in 1990, the IRS staff fell to 22 from 44 per thousand Americans. In that time frame, Americans’ tax payments soared to $3.6 trillion from $1.1 trillion.

That sounds like healthy growth; in fact, it encompasses unhealthy tax avoidance and evasion. (“Avoidance” means taking advantage of legal loopholes; “evasion” is a potentially criminal act.)

The IRS has responded to its straitened circumstances essentially by withdrawing from battle — at least, battle with taxpayers who are manifestly favored by members of Congress. The inspector general for tax administration reported in May that the agency has been allowing an increasing share of non-filers — taxpayers who don’t file a return at all — to skate.

Well-timed to coincide with both the terrors of Halloween and the eve of the election, the Center for Public Integrity delivers a horrifying story about how our lax enforcement of nonprofit regulations led to a torrent of mystery money in a key Senate race this year.

The inspector general observed that of the annual tax gap of $441 billion, $39 billion a year could be traced to non-filers. By the end of 2018, the inspector general calculated, more than one-third of high-income non-filers the IRS had identified in 2014-16 still hadn’t met their legal obligations and owed $45.7 billion. One main reason was that the IRS wasn’t leaning on them hard enough.

“IRS research studies from decades ago noted that at that time, the IRS pursued most nonfiler leads,” the inspector general noted. “However, with some exceptions, that no longer appears to be the case.”

Congress hasn’t entirely impoverished the IRS. After passing a massive tax cut aimed chiefly at corporations and the rich in 2017, Republicans gifted the agency with $320 million in new funding. But as a 2018 analysis by ProPublica noted, the money could be spent only on devising regulations to put the tax cut into action. Not a dime was to be spent on enforcement.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.