Column: Trump’s plotting for a pre-election vaccine carries real dangers for your health

- Share via

The Trump administration is plainly counting on a vaccine for COVID-19 becoming approved by the Nov. 3 election, in the expectation that news of the discovery will inspire a tide of public optimism that will sweep Trump to reelection.

Here’s a more judicious counsel about how you should be reacting to the administration’s push for rapid approval of a vaccine: Be afraid. Be very afraid.

Premature approval of a COVID-19 vaccine will sabotage public confidence in its safety. That in turn will give fuel to the anti-vaccine movement, undermining public health by allowing a resurgence of vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles.

When I hear things like ‘emergency use authorization’ I get very worried, because we’ve never done that for a vaccine that’s going to be given to a large segment of the population.

— Dr. Peter Hotez, Baylor School of Medicine

Trump’s attacks on the Food and Drug Administration, which must certify that any vaccine is safe and effective, already have undermined public confidence in the agency’s determination to hew to hard science in approving a vaccine, rather than crumbling to political pressure.

The reputation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a second key federal public health regulator, has also been sapped by indications that it has tailored its recommendations related to COVID-19 to fit Trump’s political strategy.

In late August, the CDC abruptly tightened its guidelines on who should get tested for the disease, suggesting that people without symptoms shouldn’t bother.

That ran counter to recommendations by public health experts, who maintain that widespread testing is crucial for controlling the disease. But it fit Trump’s desire to have less testing, and therefore less evidence of new COVID-19 cases.

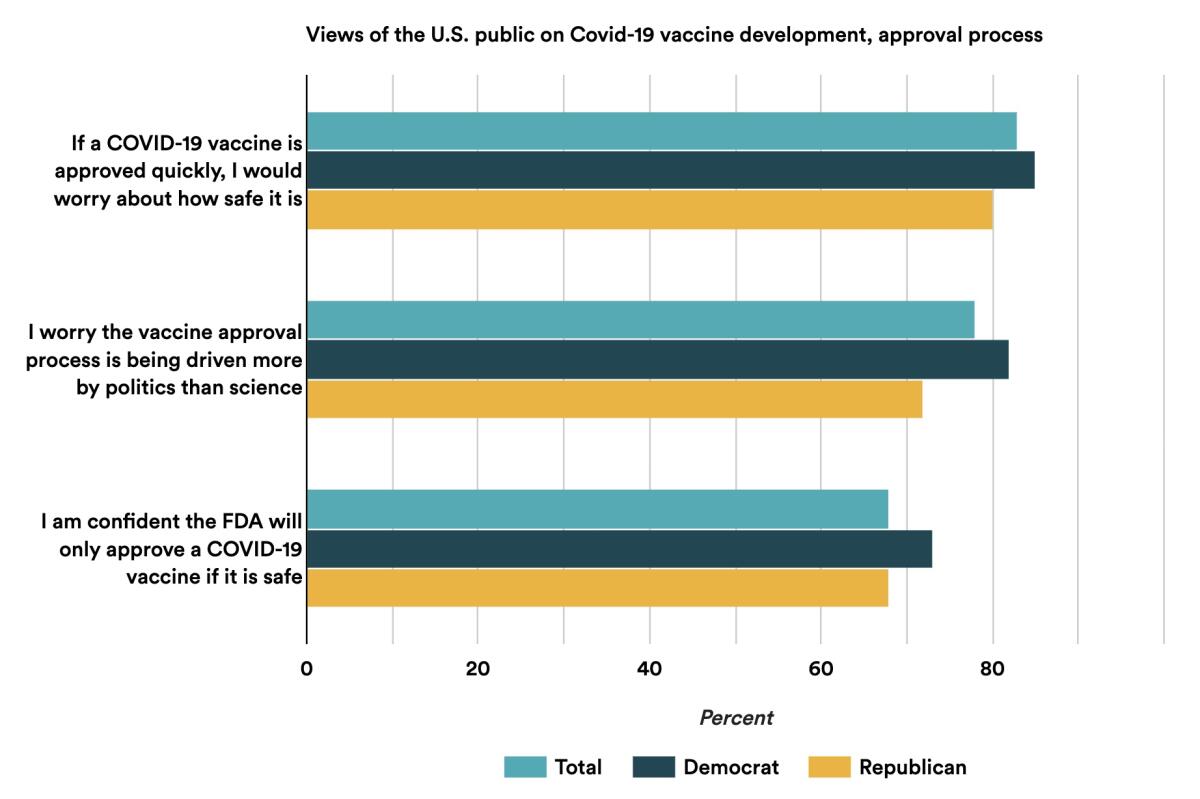

In a recent poll by the healthcare news website Stat, more than 70% of respondents said they worried that politics is driving the approval process and more than 80% doubted that a quickly approved vaccine would be safe.

Trump attacks the Food and Drug Administration and undermines its science while its leadership stays silent.

Concerns have been heightened in recent days with the disclosure of a letter from CDC Director Robert Redfield asking governors nationwide to waive health regulations in their states in order to allow government-funded vaccine distribution centers to open by Nov. 1.

It was lost on no one that the deadline comes two days before the presidential election, and that under normal circumstances there would be no reason to clear away state and local regulations on such a tight schedule. Indeed, experts are highly skeptical that any vaccine could be established as safe and effective, or ,ready for large-scale manufacture just two months from now.

Officials in California, New York and Washington state have said that they will need solid evidence of a vaccine’s safety and effectiveness before allowing it to be distributed in their states, regardless of any federal clearance. Other states may follow.

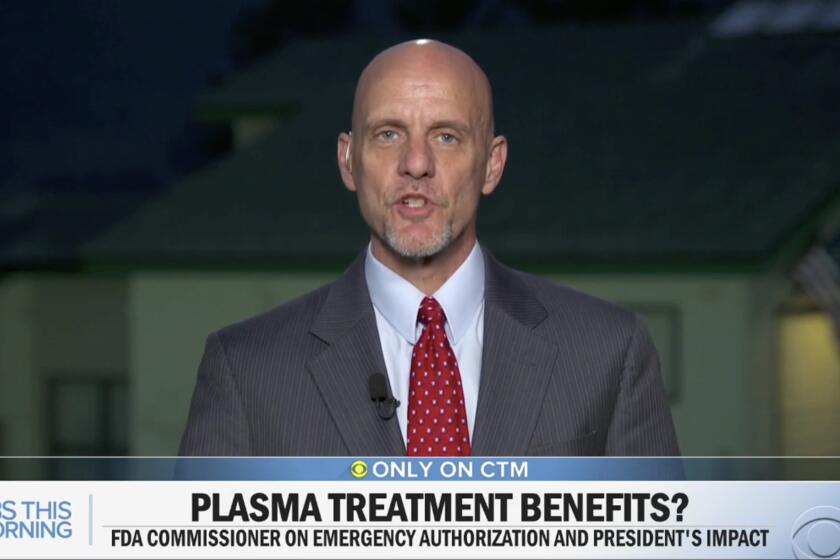

The performance of FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, an oncologist, has fed doubts about whether he can guide his agency through political shoals as it faces its most consequential regulatory decision in decades, maybe ever. A COVID-19 vaccine is seen as the key, possibly the only key, to restoring the U.S. and global economies to post-pandemic normality.

Public acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine — and therefore its potential to stop the spread of the virus — will depend not merely on the vaccine’s safety and efficacy, but the public’s perception of those qualities. And that requires confidence in the FDA’s commitment to scientific rigor and in the CDC’s integrity.

“I would feel completely confident in taking as a patient or giving to my family any vaccine that gets licensed in the U.S.,” Peter Hotez, a virology and vaccine development expert at Baylor College of Medicine, told me. “The U.S. has a very robust system for approving vaccines for licensure with a great track record for picking up safety issues and determining whether vaccines are effective.”

What gives Hotez pause, however, is the prospect that “there will be an attempt to mess with that system.”

Hahn, for example, has said that he might be willing to circumvent the full approval process, possibly by issuing an emergency use authorization allowing a vaccine to be used on certain patients even if it has not passed through complete review.

Hahn acknowledged in an interview with the Financial Times that the prerequisites for such authorizations fall far short of those for full licensure, but they may be appropriate if “the benefit outweighs the risk in a public health emergency.”

Commissioner Stephen Hahn has damaged the credibility of the FDA at a time when the agency’s trustworthiness may be more important than ever.

“When I hear things like ‘emergency use authorization,’ I get very worried,” Hotez says, “because we’ve never done that for a vaccine that’s going to be given to a large segment of the population. There’s a good reason for that, because an EUA is a substandard type of review. We’re talking about an EUA for a brand-new technology that has never achieved licensure for anything.”

Only once has the agency issued an EUA for a vaccine — for anthrax in 2005.

The FDA’s recent record on EUAs is not encouraging. The agency issued an EUA for use of the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 cases on March 28, almost certainly in response to Trump’s relentless public championing of the drug and despite the lack of solid scientific evidence that it was useful.

Embarrassingly, the FDA revoked the EUA on June 15, after scientific studies showed that it was ineffective and in some cases even dangerous.

Then, on Aug. 24 — after Trump had accused the FDA of blocking approvals for COVID-19 nostrums to hurt him politically, the agency approved an EUA for convalescent plasma, a blood component from patients who have recovered from COVID-19 that is thought to have treatment potential against the disease in new patients.

At a White House news conference announcing that EUA, Hahn grossly misstated the scientific data supporting the treatment, exaggerating it in a way that conformed to Trump’s statements, but didn’t reflect the clinical evidence. Hahn had to walk back his statement a day later, but his and his agency’s reputations may not have recovered.

Three vaccine candidates have launched Phase 3 trials in the U.S. The biotech company Moderna and Pfizer and research partners are separately testing vaccines based on an immunization model employing messenger RNA that has never been used before. AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford have launched a U.S. arm of a global test of a vaccine developed from a chimpanzee virus.

Talk of ‘warp speed’ and ‘moonshot’ science misleads the public into expecting miracles

Phase 3 trials are the final step in vaccine approval. They involve recruiting thousands of healthy individuals and comparing their experience upon exposure to a disease with that of thousands of subjects receiving a placebo, with the two groups selected at random.

Recruitment for the Moderna and Pfizer trials, which will require 30,000 subjects each, only began on July 27 and is not yet complete. U.S. recruitment for the AstraZeneca vaccine, which also seeks 30,000 volunteers, only began within the last few days.

That means the CDC’s timeline is highly improbable.

“You need to enroll 30,000 people, you need to administer the vaccine and watch for any adverse outcomes, you need to do follow-up testing, and if it’s a two-step vaccine [requiring two separate doses] you need to bring them back 28 days later,” says Saskia Popescu, an epidemiologist at the University of Arizona. “Then you need to analyze the data. These things take time, and one or two months to have all that happen seems not even feasible.”

The three vaccine trials are all being undertaken in part with funding from Operation Warp Speed, a White House initiative to hasten vaccine development that has already invested $10 billion, according to Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar and Moncef Slaoui, the chief scientific advisor to Warp Speed and a former Moderna board member.

It’s true that progress on finding a vaccine against COVID-19 has been made at an unprecedented rate. Several dozen vaccine candidates have entered clinical trials around the world, although most are in early trial stages aimed at determining safety and involving relative handfuls of test subjects.

Experts acknowledge that carrying large-scale human trials through to their ultimate conclusion might not be necessary. Infectious disease expert Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health said recently that Phase 3 trials could be halted early if interim results were so overwhelmingly and indisputably positive that they left no doubt about the safety and efficacy of the vaccines.

Within 48 hours of Moderna’s vaccine announcement, its execs sold $29 million in shares.

But that would be an extreme case, and might shave only a few weeks off the trial process, Fauci told Kaiser Health News.

The consequences of a botched rollout — whether because unexpected side effects surface after the vaccine is in wide use or because of flaws in the manufacturing or distribution process — could be dire.

In 1955, one such manufacturing glitch halted the nationwide campaign to vaccinate children against polio in its tracks. A small Berkeley manufacturing firm, Cutter Laboratories, allowed a live polio virus to contaminate some of its batches of the Salk vaccine, which was based on a deactivated virus.

An estimated 40,000 children contracted polio from the Cutter vaccine. About 200 victims were permanently paralyzed, and 10 died. Public confidence in the polio vaccine evaporated, not to be restored for years.

Another glitch occurred in 1976, when President Gerald Ford called for a warp-speed vaccination of the entire U.S. against the swine flu. Safety lapses led one manufacturer to produce a vaccine for the wrong virus, the approved vaccine failed to immunize many children, and troubling side effects appeared.

All this “added to the early momentum of the anti-vaccine movement,” observed an article published by JAMA Network in May.

Testing vaccines for the coronavirus raises tough ethical questions

What generates doubts about the administration’s commitment to rigorous vaccine testing and oversight is an approach that combines adherence to a political timeline and confused and self-contradictory messaging in all other respects.

“The appearance is that things are in disarray,” Hotez says, with the FDA, CDC and the National Institutes of Health contradicting each other’s assertions.

On Wednesday, after Redfield’s letter bearing a Nov. 1 deadline, for instance, NIH Director Francis Collins told CNN that having a vaccine by the end of October was “unlikely.” The FDA’s EUA on convalescent plasma was delayed for a time because Fauci and other NIH authorities objected that it was premature.

Meanwhile, Operation Warp Speed has done no communications outreach at all to explain its principles or timeline to the public. Instead, it has left that task to the drug companies, which are not habitually inclined to be circumspect.

As a result, the public has been inundated with manifestly premature reports on incomplete trials, invariably expressing optimism about their progress. No one benefits from this process except the drugmakers, their executives and their shareholders.

A perfect example comes from Moderna, the money-losing biotech company that announced encouraging results from an early-stage vaccine trial, based on exceedingly thin data, in May. As we reported, the firm’s top executives reaped a $29-million windfall by selling stock after its shares surged on the vaccine news.

The confusion from Washington is presenting the anti-vaccination lobby with a golden opportunity to sow more doubt about the safety and effectiveness of all vaccines.

“They say vaccines aren’t adequately tested for safety and they’re rushed,” Hotez says. “Everything this administration is doing is all feeding into that.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.