Congress members think $600 is too much to pay workers. Here’s what the lawmakers get

- Share via

This was probably not their goal, but the assertion by several senators and representatives that the $600 weekly bump in federal unemployment benefits is so generous that it’s keeping workers from voluntarily returning to work during the pandemic prompts us to look at how hard those lawmakers themselves work for their money.

Spoiler: Not very hard.

Opposition to extending the $600 weekly payment, which expires this week, is concentrated among Republicans on Capitol Hill, perhaps out of pure coincidence.

‘I promise you over our dead bodies will this get reauthorized.’

— Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), on the $600 unemployment benefit

The opening counterbid by Senate Republicans in negotiations with Democrats over a new round of coronavirus stimulus would cut the stipend to $200 a week, pending a capping of the benefit at 70% of a worker’s pre-pandemic income by October.

(It’s proper to note that many state unemployment agencies, which manage the benefits, say making such a change would be administratively impossible.)

The lawmakers’ conviction that $600 a week is so lavish that it prompts workers to stay home rather than returning to work — never mind that many have no way of knowing whether they’re safe from COVID-19 infection at work — suggests that the senators and representatives making this point have utterly lost touch with the realities of daily life as it’s lived by their constituents.

That’s true enough in normal economic conditions, and much more so in the pandemic era.

Their viewpoint evokes the scene in the 1956 boxing expose “The Harder They Fall” when Humphrey Bogart, having discovered that the punch-drunk fighter he’s been managing has been cheated out of almost all his winnings, confronts boss Rod Steiger.

“You want me to tell him that all he gets is a lousy 49 dollars and seven cents for a broken jaw?” Bogie, his hands balled into fists, upbraids Steiger. “How much would you take?”

True populists wouldn’t be punishing workers by cutting their unemployment benefits.

Here’s Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) talking of the prospect of extending the $600 benefit: “I promise you over our dead bodies will this get reauthorized.”

So let’s examine how much the average federal lawmaker does take to live his or her toilsome life.

As a starting point, let’s consider that the salary for senators and representatives is $174,000 a year, or $3,346 a week. (The House speaker and the other three partisan chamber leaders get a bit more.)

The basic salary is more than three times the median earnings of full-time workers in mid-2020, which was $52,104. Women, by the way, earned 84% of the male average, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

So the lawmakers rank among the elite among wage slaves. What about the physical burden of their labor?

It’s fair to say that the jobs of elected officials on Capitol Hill fall into the “no heavy lifting” category. They’re not hoisting girders or carrying bricks in a hod. They don’t typically face workplace injuries that would send them to the hospital.

Perhaps more importantly, they have lots of help. Each House member receives about $1 million to hire up to 18 permanent aides, plus more for other office expenses. Senators each received an average of about $3.5 million in 2017, according to the Congressional Research Service, that they can spend as they see fit on personnel or supplies.

The lawmakers receive health coverage and can qualify for federal retirement plans if they serve at least five years. They pay into and are eligible to receive Social Security.

Obviously these are benefits not offered to all American workers. In fact, Republicans as a group are pushing to deprive millions of workers of health coverage provided through the Affordable Care Act by supporting a federal lawsuit that would repeal the ACA. The lawsuit will be heard by the Supreme Court, probably later this year.

The Republican proposal on coronavirus relief puts all the risk from catching COVID-19 on workers.

Lawmakers certainly can lose their jobs, but seldom as a result of arbitrary decisions by their employers, the electorate. Senators or representatives who get turned out of office generally have only themselves to blame — they’ve misjudged the political weather at home, or committed a crime or some egregious act of moral turpitude, for instance.

Rank-and-file workers, by contrast, are typically considered “at will” employees — they can be fired for any reason except an illegal one, unless they’re represented by a union contract that sets hiring and firing terms.

Senators and representatives can even get paid when they’ve taken steps to make sure they have no work to do. That happened during 35 days in 2018-19, when their failure to do their jobs resulted in the longest government shutdown in history. They continued to collect their paychecks, however, even as 800,000 federal workers had to go without.

There’s another aspect of many workers’ jobs that members of Congress don’t seem to suffer from: boredom. According to a survey conducted in 2013 by the Congressional Management Foundation and the Society for Human Resource Management, about 95% of members agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “My work gives me a sense of personal accomplishment.” How many of you out there could say the same?

That brings us to the question of how much time a member of Congress actually spends on the job. It’s hard to answer, highly dependent by how one defines the job. In the narrowest sense, defined by the number of days Congress is in session in Washington, the answer is Not Much.

Social Security advocates are universally opposed to the measure, which they see as an expression of longtime conservative hostility to the program.

According to a recent study, the House averaged fewer than 147 legislative days per year since 2001, and the Senate 165 days. A full work year is about 250 days, so the House worked three days out of five and the Senate a bit more.

It’s fair to acknowledge that a work day or work week for an elected official might bear little resemblance to that of a salaried worker.

The 2013 management survey found that members worked an average of 70 hours a week when their chamber was in session and 59 hours when it was out of session. Plainly that outstrips the 40 hours typically judged to be a full work week in the outside world.

It’s difficult to validate those claims, however. Senators and representatives don’t have to punch a clock, and they can count as work time activities that others might view as leisure — parties, meetings with donors on the golf links, etc., etc.

We plead guilty to having written before that Congress actually deserves a raise. The current salary hasn’t been changed since 2009.

This is a complicated issue. Leaving the wage where it is or even cutting it, as some have proposed, would make Congress worse. It would turn Capitol Hill into more of a hive for plutocrats than it is now by making it harder for those with modest resources to run for and stay on Capitol Hill.

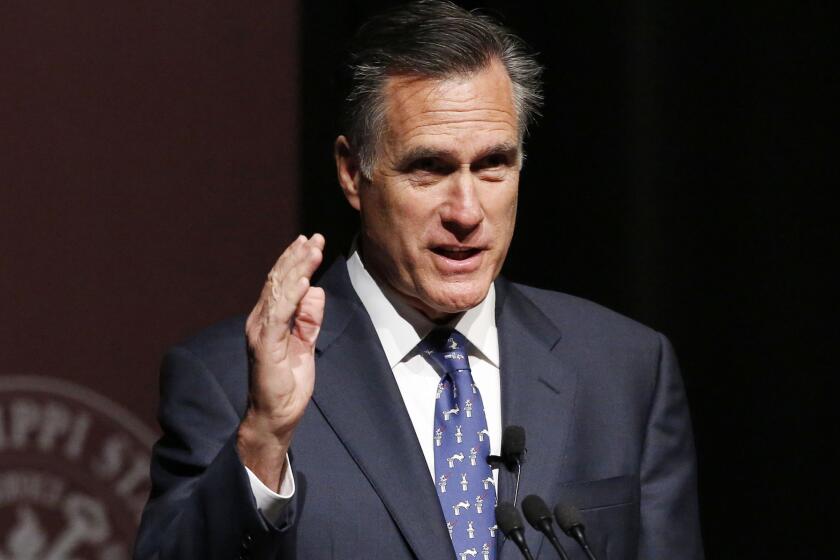

Followers of the business and political career of Sen.

Interestingly, the last politician to propose cutting congressional salaries was Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.), a multibillionaire. Scott portrayed his proposal as a blow for populism, but its effect would be to make the members of Congress look more like him, and who needs that?

But senators and representatives don’t make it easier to do the right thing by them when they whine and grouse about their lot in life, or imply that the average working men and women are one $600 check away from frittering their days on the couch popping bonbons instead of doing honest work.

During a 2013 government shutdown, then-Rep. Phil Gingrey (R-Ga.) was overheard grousing that while his staffers could hop to a lobbying job and make $500,000, “I’m stuck here making $172,000 a year.” (Actually, $174,000.) Gingrey later joined a lobbying firm.

The problem with members of Congress who promote the myth that the $600 unemployment bonus is just gravy keeping people from working, rather than money they need to stay afloat, is that they’ve forgotten how the other half lives.

Did I say “other half”? Most Americans up and through the middle class struggle to make ends meet. Nearly half of households responding to a Federal Reserve survey in 2014 said they’d have trouble raising $400 cash for an emergency.

These people asserting that $600 a week is just too lavish should spend a few days walking in their constituents’ shoes. They’d discover that they pinch, but hard.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.