Hard-hit by break-ins, the Jewelry District never lets its guard down

- Share via

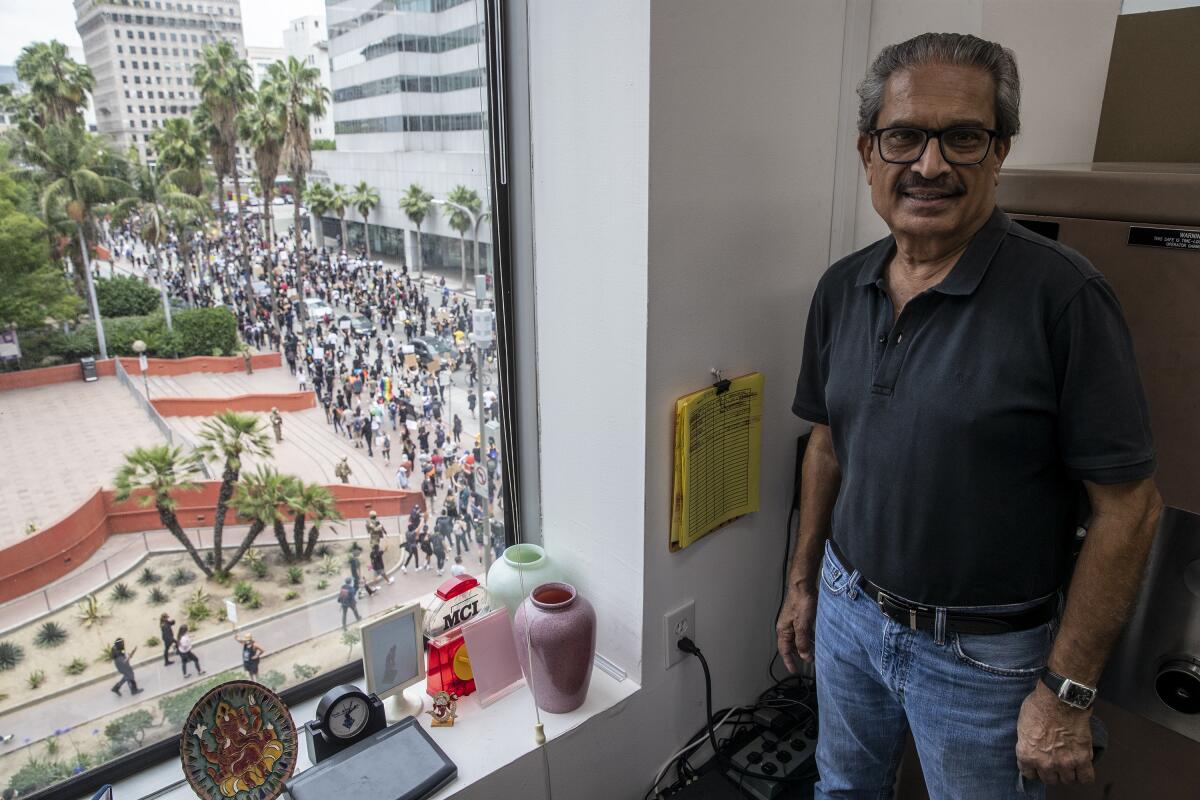

On Tuesday afternoon in downtown Los Angeles, as another protest sparked by the police killing of George Floyd wound past Pershing Square half a block away, a diamond dealer named Sanat Shah stood on the sidewalk of Hill Street and pointed out the handful of buildings that constitute the largest concentration of gem and jewelry businesses west of Manhattan.

All along Hill and around the corner to Broadway, store windows that usually glittered with gems were boarded up. On the previous Friday night, mass protests had been followed by break-ins after dark, when burglars forced up metal security grates, shattered windows, and grabbed fistfuls of gold and jewels from some of the storefronts in the three-block Jewelry District. Shah, who has worked in the district since 1983, said that this was the first time in his memory that civil unrest had swept through the area.

But the storefronts represent only a small portion of the real gem trade downtown. The vast majority of the district’s assets — and Shah’s own diamonds, as a private dealer who mostly sells to other businesses — were secure in locked safes in private offices or behind guarded storefronts on upper floors, backed up by insurance policies designed for an industry accustomed to dealing with sophisticated thieves and high-dollar losses.

Although the wave of smash-and-grab burglaries caught most businesses by surprise, hyper-vigilance is the norm in the high-value jewelry trade, where owners have to be prepared for coordinated attacks and armed robbery as a matter of course. Many in the business have been on high alert since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, taking extra precautions as stores and retail corridors sit empty, seemingly easy targets.

Most retail businesses can call any number of insurance companies to take out a policy that covers damage or theft to their inventory. As The Times has reported, those policies will probably cover most of the losses that businesses have suffered in the last week’s spate of unrest.

But big insurers won’t touch jewelers, let alone specialized diamond dealers, whose inventory is valuable, portable and difficult to assess.

Overall jewel thefts, like all crime in the U.S., has declined in the last 20 years. In 2018, jewelers nationwide lost a little more than $53 million to theft, according to statistics from the Jewelers’ Security Alliance, an industry group in New York City’s diamond district in Midtown Manhattan. In 1998, adjusted for inflation, the losses almost hit $200 million.

Back in his office on the fourth floor of the California Jewelry Mart, which houses a warren of small jewelry shops and nondescript offices on each floor, Shah described the kinds of threats that he and his colleagues have faced for years.

Organized crews of robbers, broadly classified as South American Theft Groups by the FBI, made headlines in California from the late 1980s through the 1990s and early 2000s, and have continued to target jewel dealers in transit in the years since. “When we go out to Pershing Square, when we go to the parking lot, we are always worried.”

Shah flagged down a passing colleague, Mervyn Hahn, who operates a showroom on the building’s second floor and has been in the business since 1980, to join the conversation. “They’re watching 10, 15 hours a day, standing in Pershing Square, headphones in, waiting for us to leave,” Hahn said. The thieves’ M.O., both men said, was to select a target in advance and follow them once they left the lot. In some cases, they would punch a slow leak in the target’s car tire in advance. In others, the thieves would rear-end the car in traffic. With the car disabled, the thieves would offer to help — and spring the trap.

Shah said that he had been pursued in the past, and experienced some close shaves, but has never been robbed or burglarized. Both men knew colleagues who had been hit, some as recently as this year.

For retail stores, the greatest number of burglaries are simple nighttime smash-and-grabs of display cases that take less than three minutes, according to the Jewelers Security Alliance. But more sophisticated thieves targeting safes are still carrying out heists — in 2017 and 2018, burglars in the U.S. disabled alarm systems and entered jewelry stores through holes drilled in the ceiling 27 times.

When working with such high-value inventory, there’s always the risk that dealers or their employees might experience a lapse in ethics. “There’s a lot of mysterious disappearance, quote unquote, in this business,” Shah said. “Someone can fit 2 million worth of diamonds in their left pocket and say they lost it, you know what I mean?”

Jewelers Mutual is one of the few insurance companies willing to work in such dangerous terrain, and is one of the leading jewelers’ insurers in the country as a result.

Jamie Luce, executive vice president of the Neenah, Wis., company, said that its standard policies that cover jewelers’ gem assets — known as block policies in the business — will cover this week’s losses just like they cover any other theft.

“The kind of events we’re seeing right now are very atypical — we don’t see looting and rioting on a frequent level — but very routinely things that are not in the headlines are costing our jewelry clients millions of dollars a year,” Luce said. “Most of the high-dollar amounts that are paid are tied to very coordinated attacks on jewelers.”

Their claims adjusters lean heavily on documentation of inventory to determine the value of anything lost, but the amount of coverage depends on the situation. Jewels in a safe, jewels out on loan for inspection to other jewelers, and jewels that are carried in hand or in a bag are all covered differently, and additional security measures such as armed guards and more advanced alarms factor into the insurance equation.

John Fierst, vice president of commercial lines at Jewelers Mutual, said that 2019 was an especially busy year for burglaries, and the company had been concerned that the coronavirus shutdowns might leave empty stores susceptible to even more theft. So the company has been offering to pay for armored car transportation and secure storage for its customers with Malca-Amit, a company that specializes in high-value logistics. In Los Angeles, Malca-Amit operates a secure and guarded vault right on Hill Street along Pershing Square.

Crime is hardly the only threat facing the Jewelry District, Shah and Hahn said. Shifting consumer habits have taken a bigger toll.

Both recalled how, when they started out in the 1980s, their building would be full with shoppers on weekends who came downtown from all over L.A. County to comparison shop for deals on diamond jewelry. Among jewelers, competition for retail space was so stiff that a dealer with a prime spot on the third floor could demand $80,000 upfront to transfer the lease to a new tenant. By the early 1990s, as Southern California’s economy flagged under a recession, the business had changed.

In the last two decades, competition from online sales, the growing popularity of synthetic diamonds, and millennial shoppers’ lower interest in buying jewelry have hit the district hard. Now the margins for the small shops downtown — in contrast to brand-name behemoths such as Tiffany, which often charge two to three times more for similar items — hover around 15%, Hahn said.

But that hasn’t stopped Shah and Hahn from sticking to the business after 37 and 40 years, respectively, and continuing to add new inventory even while demand stays flat.

“If we see profit in a stone, we’ll buy it,” Hahn said, “even if we’ve got five of them already.”

“It’s not vegetables, it’s not clothes,” Shah said. “I can always put a stone in the safe because diamonds and gold don’t lose their glitter.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.