Column: Despite rising pandemic costs, Republicans are already talking about cutting off aid

- Share via

As any follower of our nonsensical fiscal policy-making would have guessed, federal spending in the coronavirus crisis wasn’t completely done before Republicans in Washington started calling for austerity.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) got the ball rolling Tuesday, following Senate passage of a $484-billion phase three stimulus bill, when he told reporters that he was skeptical that more money would solve the nation’s coronavirus “problem.”

State and local governments are projecting mind-blowing deficits and don’t have the funds to pay for the testing and patient-tracing needed to ensure safety for their citizens, and hospitals and other healthcare providers are cracking under financial strains.

We’re not ready to just send a blank check down to states and local governments to spend any way they choose to.

— Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell

Yet McConnell said it’s “time to begin to think about the amount of debt we’re adding to our country and the future impact of that. ... Until we can begin to open up the economy, we can’t spend enough money to solve the problem.”

Speaking on right-wing commentator Hugh Hewitt’s radio show Wednesday, McConnell went further, spiking his remarks with open partisanship.

“We’re not ready to just send a blank check down to states and local governments to spend anyway they choose to,” he said, presumably aware that Hewitt would accept his remarks uncritically.

You may remember all the glowing predictions made for the December 2017 tax cuts by congressional Republicans and the Trump administration: Wages would soar for the rank-and-file, corporate investments would surge, and the cuts would pay for themselves.

He attributed the states’ fiscal crises to “problems that they created for themselves over the years with their pension programs,” thus taking a swipe at public employees, who apparently according to McConnell don’t deserve to have reasonable retirements.

He even plumped for allowing states to go bankrupt, though he acknowledged that no provision of bankruptcy law provides for that.

“There’s no good reason for it not to be available,” he said. “My guess is their first choice would be for the federal government to borrow money from future generations to send it down to them now so they don’t have to [declare bankruptcy]. That’s not something I’m going to be in favor of.”

Incredibly, McConnell told Hewitt: “There’s not going to be any desire on the Republican side to bail out state pensions by borrowing money from future generations” — this after he arranged to borrow an estimated $2 trillion from future generations over 10 years to fund a Republican tax cut that fills the pockets of the wealthy.

McConnell’s office labels requests for state and local assistance “blue state bailouts.” As we’ll see in a moment, this is exactly wrong.

But in a general sense, he must know that statehouses coast-to-coast will be budgetary black holes over the next few years because of higher spending on the coronavirus fight and lower revenues because of the economic shutdown.

Let’s not overlook that he’s talking about depriving states and localities of funds to pay police and fire fighters and teachers. And their share of the expense of providing healthcare to the indigent via Medicaid.

Could he really believe that bankrupting states, including his own, is a good political strategy, or responsible public policy?

Of course, there may be no better point in history for the U.S. government to borrow to fund a pandemic response, and much more, than today, when interest rates on federal debt are hitting rock bottom.

But deficit-mongering is a familiar feature of our politics. Faced with a crisis, politicians pledge to spend every dollar necessary to solve it. Once the size of that commitment becomes clear, they start backing down, often at a pace that only the most sensitive speed guns can measure.

The result is that the government often fails to spend what really is needed, or curtails programs before they’ve begun to show results. That’s what happened in the financial crisis, when the $787-billion stimulus act of 2009 proved to be too small and too focused on tax cuts to avert a recession and a slow recovery.

It also happened during the New Deal, when the $3.6-billion federal deficit of 1934 was judged by progressive economists to be as little as 60% of what was needed to pull the country out of the Great Depression.

In both cases, hand-wringers about the federal deficit got in the way of a full-throated, effective stimulus. That’s happening again. But this time, the arguments are more cynical than ever, because they’re directed at shortchanging rank-and-file American workers after the rich have already been paid off.

At least one federal government official is still speaking rationally. That’s Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin, who has helped negotiate the coronavirus assistance bills and on Wednesday stated on Fox Business, “This is a war, and we need to win this war and we need to spend what it takes to win the war.”

All Washington seems to be buzzing this week over a single question: Is Sen.

The $484-billion measure approved by the Senate is the third bill considered by Congress in the crisis, following the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the $2-trillion CARES Act, both enacted last month. Since the length and depth of the crisis can’t yet be known, there’s a widespread assumption that more will be needed.

What makes McConnell’s hand-wringing about the impact of these measures on the federal debt so hypocritical is that a huge proportion of the debt arises from the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017, which was passed by a Republican Congress and signed by President Trump. The tax cuts went overwhelmingly to corporations and the wealthy, who didn’t need tax relief in the booming economy of that period.

Although the tax cuts were billed as paying for themselves by turbo-charging the U.S. economy, that never happened. The sugar high produced by the tax cuts had dissipated by early 2019.

After a rise in annualized growth rates to more than 3% during a few quarters in 2018 and early 2019, economic growth fell back to annualized levels of roughly 2%. Rank-and-file wage growth barely budged, but corporate stock buybacks, which flow into the pockets of shareholders, surged to a record.

The tax cuts did, however, blow a hole in the federal budget that will add almost $2 trillion to the federal debt over the next decade, according to a calculation by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. When McConnell starts fretting over “the amount of debt we’re adding to our country and the future impact of that,” he should start fretting with his own tax cut for the rich.

This isn’t a new spiel for McConnell, by the way. In 2018, not long after doling out benefits for his rich patrons, he had the temerity to claim that “entitlements” — Washington-speak for Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid — were “the real drivers of the debt” and called for them to be adjusted “to the demographics of the future.”

Trump’s global trade war costs the U.S. crucial medical supplies in the thick of the coronavirus pandemic.

Translation: He was talking about cutting benefits.

These points are not the most cynical aspect of McConnell’s plaint, however. It’s the characterization of assistance to states and localities as “blue state bailouts” — that is, Democratic state bailouts.

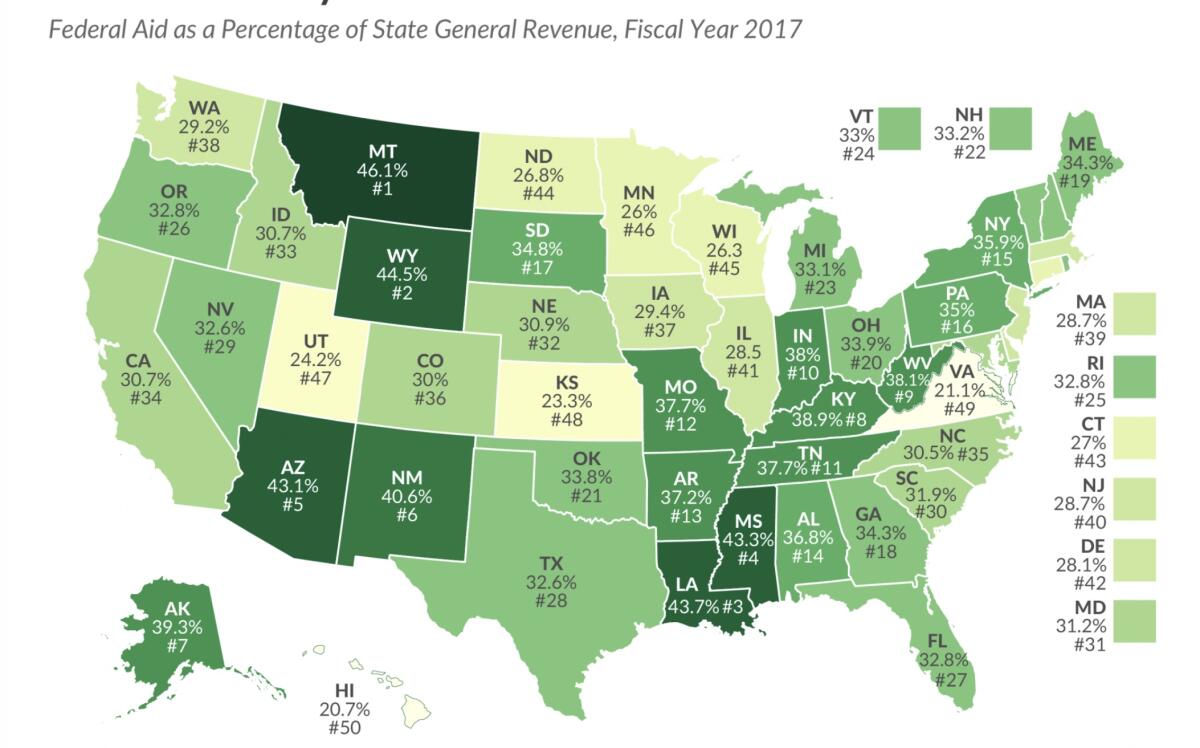

The truth is that red states — Republican states — have been consistently supported most by the federal government. According to the Tax Foundation, among the states ranking highest in terms of federal aid as a percentage of general state revenue are red states Montana (No. 1), Wyoming (2) and Mississippi (4). Among the biggest beggars at the federal almshouse is McConnell’s home state, Kentucky, which ranked eighth.

New York ranks high at No. 15, but many of the other biggest blue states are on the bottom half of the list, including California (34), Washington (38) and Illinois (41).

According to another metric, blue states tend to be the biggest net contributors to the federal government, judged by the net outflow of their residents’ tax payments versus federal income flowing back.

The biggest loser there, according to an analysis of 2017 figures by the Rockefeller Institute of Government, is New York, which gets 86 cents back for every dollar it sends to the feds. The biggest winner? Go figure — it’s Kentucky, which gets $2.35 back for every dollar it sends to the feds.

President Trump lies again about the reasons for the Postal Service deficit

In other words, McConnell is just engaging in fatuous blather. His real targets are public employees, because they tend to vote Democratic. Given his attitude, why wouldn’t they?

It’s proper to acknowledge that, in historical terms, deficit-worrying hasn’t been exclusively a Republican position. It always is a conservative position, however, and generally aligned against policies that assist middle- and lower-income Americans rather than the wealthy.

For instance, in 1938, soon after the Roosevelt administration halted a recession with a fiscal stimulus package, Sen. Harry F. Byrd of Virginia, a Democrat, went before a taxpayer group in Boston to decry “the present orgy of spending.” He demanded a balanced federal budget, a ruthless purging of relief rolls, and the end of “dispensable” public works projects.

McConnell is wearing the garb of a present-day Byrd, calling to sacrifice the most vulnerable Americans in pursuit of an imaginary fiscal balance. The lesson of history is that when a crisis calls for spending what it takes to defeat an enemy, whether it’s a foreign power, an economic collapse or a virulent microbe, spending less only means prolonging the pain and perhaps losing the war. McConnell and his fellow Republican are setting up the American public for death and defeat.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.