Column: Here’s why a COVID-19 vaccine could end up costing you a small fortune

- Share via

Things have gone from bad to worse for Brian Helstien. For a decade, he’s been grappling with multiple myeloma, a form of blood cancer. Now he needs surgery for a leaky heart valve.

But because his medical network, Kaiser Permanente, like all healthcare providers, is dealing with a tsunami of COVID-19 patients, the Laguna Woods resident has been informed his non-life-threatening ticker trouble is an “elective” procedure.

“They said maybe they’ll be able to get to me in three to six months,” Helstien, 71, told me. “As if we were talking about a nose job instead of heart surgery.”

In the meantime, he’ll have plenty of time to ponder the high cost of being sick in America.

Helstien faces a list price of nearly $20,000 a month for his cancer pills, although his out-of-pocket cost with insurance is much lower.

That should serve as a warning for anyone wondering how much a COVID-19 vaccine might cost.

The harsh reality is that the United States is one of the few developed countries that allow pharmaceutical companies to charge whatever they want for prescription drugs — even when production costs are just a fraction of the list price.

Multiple myeloma is incurable but, for a time, is treatable. The American Cancer Society says patients with the most serious form of the disease may have only a few years to live.

After undergoing a stem cell transplant, Helstien was prescribed a medicine called Revlimid, which came with a price tag of nearly $16,500 a month.

When that stopped being effective, he switched to a drug called Pomalyst, which costs $19,000 monthly.

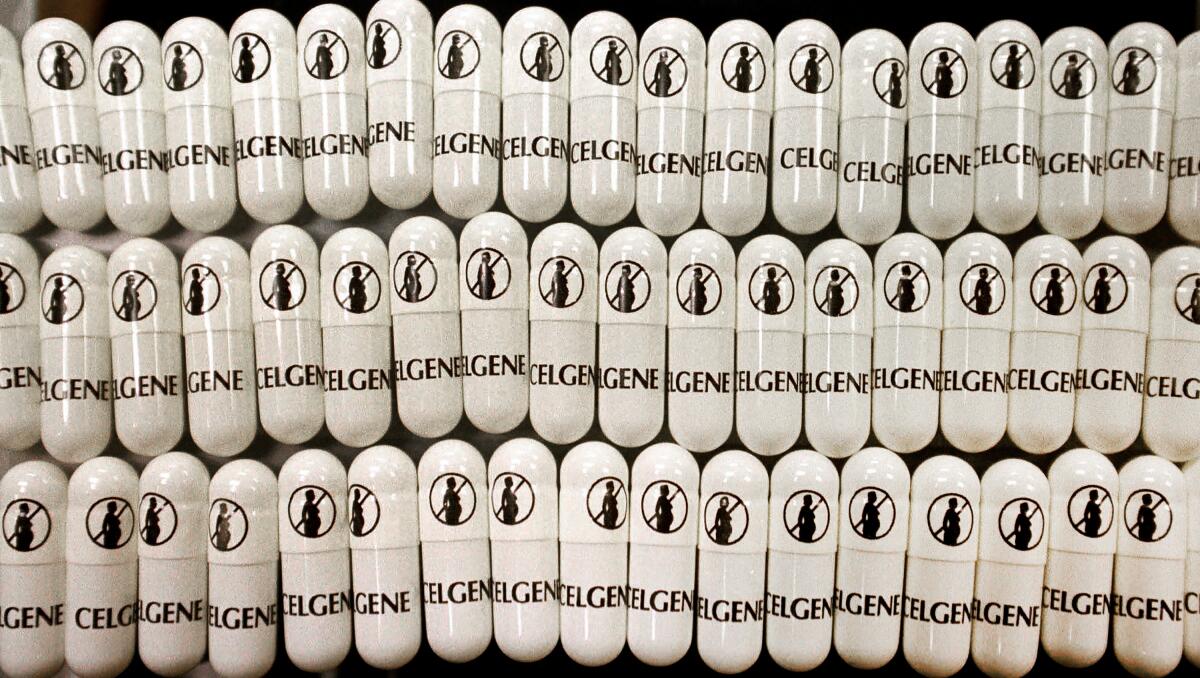

Both drugs are made by New Jersey-based Celgene, which was purchased by Bristol-Myers Squibb in November for $74 billion — one of the largest pharmaceutical takeovers ever.

Thanks to his Kaiser Medicare Advantage coverage, Helstien pays only an $11.20 co-pay for each drug purchase. That’s good for him, but it doesn’t mitigate the jaw-dropping list prices set by Celgene, which affect all insurers and their policyholders in the form of higher premiums.

Nor does it let Medicare off the hook from paying such sky-high amounts. Thanks to Republican opposition, the government insurance program, with almost 60 million beneficiaries, is forbidden by law from negotiating prices with drug manufacturers.

Drug companies typically justify high list prices by pointing to the big piles of money required to bring a new medicine to market. Such costs can run into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

However, Helstien’s high-priced meds have their roots not in years of expensive research and development, but in one of the most notorious drugs ever sold.

Remember thalidomide? It was a sedative discovered in the 1950s that was prescribed to pregnant women worldwide to relieve anxiety and morning sickness.

Researchers later found that thalidomide caused irreversible birth defects, with thousands of children born with severe malformations and many not surviving more than a few days. It was one of the darkest episodes in the history of the global drug industry.

Celgene, for its part, never lost hope.

In 1998, the company received approval from the Food and Drug Administration to bring back thalidomide as a treatment for leprosy — and, possibly, as a treatment for AIDS.

Then the company realized a modified form of thalidomide had potential as a treatment for blood cancer. Tests were promising.

Here’s where things get hinky. Celgene had to decide how to price a drug that had been around in various forms for decades but now had a completely new, and seemingly positive, use as a cancer therapy.

In a 2004 interview with the Wall Street Journal, Celgene’s then-chief executive, John Jackson, said the company knew it couldn’t boost prices when the reborn thalidomide was being touted as a possible AIDS remedy.

“There would have been demonstrations outside the company,” he admitted.

As a cancer drug, on the other hand, all bets were off.

Celgene started raising the price at regular intervals, arguing that thalidomide — now bearing the name Revlimid — should be priced at the same level as other cancer drugs on the market.

A 2017 study found that no other country charges more for cancer meds than the United States.

“By bringing it up every year, it was heading toward where it should be as a cancer drug,” Jackson told the Journal.

By 2017, Revlimid represented about three-quarters of Celgene’s roughly $13 billion in annual sales.

The company introduced Pomalyst in 2013 as an alternative to Revlimid. After multiple price hikes, it was bringing in more than $1 billion a year in revenue.

Celgene’s new parent, Bristol-Myers, rejects suggestions that its thalidomide-based drugs are wildly overpriced.

A company spokeswoman told me that “Revlimid is structurally, functionally and pharmacologically different than thalidomide, and the two drugs have different clinical, safety and toxicology profiles.”

“Additionally,” she said, “Revlimid, as well as Pomalyst, required very extensive development programs distinct from thalidomide and from each other.”

Celgene spun things differently in 2017 when it told the biotech website FiercePharma that “pricing decisions reflect the benefits that our innovative therapies provide to patients, the healthcare system and society.”

That’s a more straightforward, if disturbing, explanation — with profound implications for the list price of a possible COVID-19 vaccine, which could be available by next year.

When you’re pricing a drug relative to its “benefits,” rather than its actual production cost, you can charge as much as you like. This is why a vial of insulin that sold for $20 a quarter-century ago now sells for about $300.

“Of course Revlimid and Pomalyst are significantly overpriced, not much doubt about that,” said Rock Brynner, coauthor of “Dark Remedy: The Impact of Thalidomide and Its Revival as a Vital Medicine.”

“But are they more overpriced than dozens of other life-critical drugs?” he asked. “I don’t know.”

Indeed, there have been numerous reports in recent years of shameless greed in prescription drug pricing.

Perhaps the most notorious was Turing Pharmaceuticals buying the rights in 2015 to Daraprim, which is used to treat infections. The company raised the price overnight from $13.50 to $750 a pill.

(Side note: Brynner’s dad, Yul Brynner, co-starred in the original movie version of “Westworld,” which my dad produced. Small world.)

Two things jump out from all this. First, there’s the idea that life-saving prescription meds should be priced according to their “benefits” to patients, as opposed to what they cost to make.

That’s a recipe for financial harm, which is why most other developed countries limit drugmakers to prices that offer a reasonable profit but don’t exploit people’s misfortune.

Second, there’s the insanity of pharmaceutical companies setting list prices at absurdly high levels just so they can squeeze insurers in subsequent negotiations.

Celgene pats itself on the back for having programs aimed at defraying costs to cancer patients. “We believe patients who can benefit from our medicines should have access to them,” the Bristol-Myers spokeswoman said.

But subsidies such as these maintain the company’s ability to keep list prices artificially high.

If the pharmaceutical industry runs the same playbook with a COVID-19 remedy, the list price of a vaccine could be set stratospherically high regardless of actual R&D costs — and despite the federal government kicking in more than $3 billion for vaccine development.

Insurance premiums almost certainly would rise as a result.

The solution, as I wrote last week, is a “Medicare for all” system that allows the program to use its market muscle to negotiate fair prices.

Helstien told me he’d be good with that. For now, he’s just trying to stay healthy.

“I’ve been basically told I need to try and survive until Kaiser can fit me in for heart surgery,” he said.

And then he’ll need to survive for a few more months until there’s a shot for COVID-19. However much that may cost.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.