Charity is off the charts amid the coronavirus. Is that a sign of America’s strength or weakness?

- Share via

The coronavirus outbreak has shut down entire school districts and turned bustling commercial corridors into ghost towns, but there’s one sector of society that’s busier than ever: philanthropy.

The charitable acts have come in all shapes and sizes. Small checks to food pantries, foundations issuing emergency grants to desperate nonprofits and, most conspicuously, billionaires doling out big-dollar gifts with all the attendant publicity.

Large charitable gifts from corporations, foundations and individuals, including faith-based and other sources, hit $7.8 billion worldwide last week, with about two-thirds originating in the United States — an amount that dwarfs records set after other disasters such as Hurricane Sandy.

“It shows no signs of slowing up yet,” said Andrew Grabois, manager of corporate philanthropy at Candid, a nonprofit tracking the response. “We are just getting grants by the hour.”

Here’s how to file for unemployment benefits if you’ve lost work because of the coronavirus outbreak. Read this explainer for eligibility requirements and how the program works.

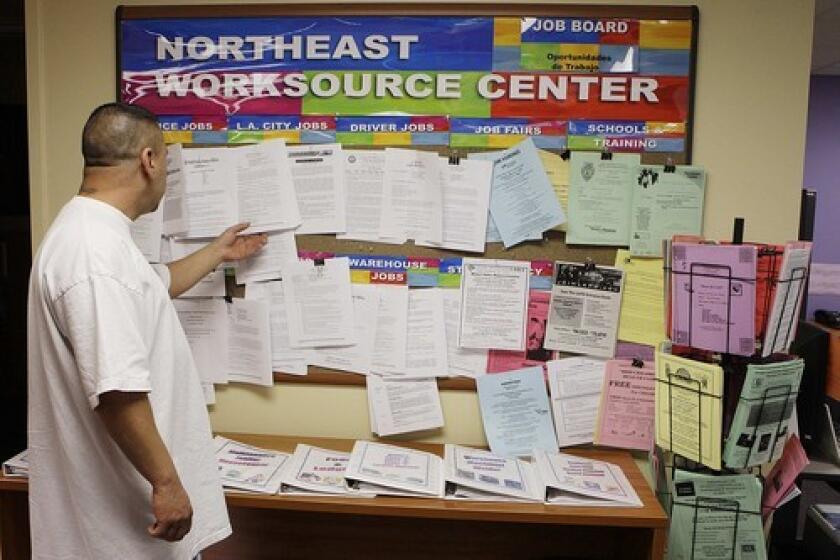

The calamity has stressed the charitable industry as it faces demands not imagined since the Great Depression. It has sent foundations scrambling to dole out the new funding to nonprofits overwhelmed by some 22 million people who have lost jobs since President Trump declared a national emergency, even as some states prepare to reopen some businesses and public facilities.

And, like much else in a modern America preoccupied by inequality, the disaster has heightened tensions in an industry dependent on much of its funding from the wealthy. Rich donors are facing calls to give more, even as some of the biggest gifts have drawn scorn from critics of so-called billionaire philanthropy.

The difficulty is reflected in the bewildering number of ad hoc funds, with nearly 100 established statewide by last week, according to a listing of vetted funds by Philanthropy California, an association of foundations and other charities.

“The challenging part is coordinating all these efforts,” said Phuong Pham, communications director of Southern California Grantmakers, a regional association that has been working to resolve the issue. “In the mid to long term, there will be fewer funds and more collaboration, but in this time we can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.”

The funds have been set up by public agencies, United Way chapters and community foundations, as well as by faith-based groups, private foundations and others. Meanwhile, there’s been a movement to relax the typical restrictions on how the money can be spent by the nonprofit agencies on the ground.

“It’s been very fog of war,” said Wendy Garen, chief executive of the Ralph M. Parsons Foundation, a Los Angeles private charity started decades ago by the founder of the Parsons Corp., which funds human services, health and other areas. “What we think we knew on Monday by Wednesday makes no sense.”

The United Way of Greater Los Angeles, which typically raises the bulk of its money from workplace and corporate campaigns, had raised $9.5 million by Friday for its coronavirus response, about half through small contributions, said Chief Executive Elise Buik. “You are just seeing a rush of giving in a very short time,” she said.

Although there is no doubt that the need is greater than private philanthropy can meet, Buik says organizations such as the United Way have been able to move faster than the government has, with her agency deploying $3.5 million through the first week of April to recipients that included homeless outreach organizations. An additional $1 million was set to be disbursed this week.

“We had a lot of vulnerable people before this started. They were living paycheck to paycheck,” she said. “This crisis for me really exposes those cracks.”

Attorney Matt Johnson, brought in to help run the coronavirus crisis response for the Mayor’s Fund for Los Angeles, said that the fund, which has received contributions from Jay-Z and Rihanna, has been focused on getting money to needy people the government isn’t serving — also a target of the United Way’s next round of grant making.

“If you are undocumented or someone in your household is undocumented,” he said, “you are not entitled to federal funds. In L.A., there are tons of families where you might have an undocumented family member living with you.”

To get a sense of the demand, consider the Los Angeles Regional Food Bank, which was given an emergency $50,000 grant by the Parsons Foundation. It has seen demand explode, and has been distributing nearly 75% more food than normal, with demand surging among hospitality workers and others.

One Saturday in March, it handed out 30-meal boxes of food to 1,159 families in Long Beach, where truckers serving the ports lost work when China factories went dark.

“It’s impacted so many sectors of our economy. It’s almost hard to wrap your mind around it. It’s like this very condensed, compacted Great Recession happening in four weeks,” said Michael Flood, chief executive of the food bank, which used the grant money to hire temporary workers.

That level of need has widened fault lines that already had appeared in the philanthropic community over the last decade, as wages stagnated while immense wealth was created in tech and other industries amid a stock market boom.

The lion’s share of the donations has so far come from corporations, whose pledges have topped $4 billion worldwide when including funds from corporate-controlled foundations. Private foundations, typically run by wealthy families or individuals, have given less than $500 million, as have private independent foundations no longer controlled by their benefactors, such as Parsons, according to Candid.

Small nonprofits have been eligible for financial assistance from the federal government’s $2-trillion stimulus package, which also temporarily increases and makes more widely available tax breaks for charitable giving. But even as the virus-related market downturn has eaten into the value of endowments, some have been calling on the wealthy and their private foundations to do more.

Nine philanthropic groups signed an April 2 open letter calling on foundations and all funders to significantly increase their spending on grants, specifically noting that black, indigenous and other communities of color are being devastated by mass unemployment. “Unprecedented challenges require unprecedented responses,” the letter said.

Private foundations are required to make an annual distribution of at least 5% of their assets, including an allowance for administrative costs — allowing them to exist in perpetuity given historical investment returns. Spending more could mean dipping into their capital, rather than just relying on returns.

“We are seeing nonprofits in communities hit by massive increases in demand coupled with declines in revenue,” said Phil Buchanan, president of the Center for Effective Philanthropy, a signatory of the letter. “I am not calling on foundations to spend themselves out of existence. There is a lot of opportunity in the future to be more prudent in the grant making or to be more savvy on the investment side and build it back up.”

The Libra Foundation, the private charity of a branch of the Chicago-based Pritzker family, is one of the few foundations that has publicly backed the letter’s call. It is doubling its grant making this year to $50 million, which represents about 10% of its endowment.

The San Francisco-based foundation, which funds social, gender and environmental justice groups, had actually decided to up its spending before the outbreak partly due to it being a U.S. census year, and it is abiding by that decision despite the market downturn, said Crystal Hayling, executive director.

“Your endowment will definitely take a hit,” she said, “and it may take you a while to build back up, but if our purpose is to respond to communities, then I think we have to put that front and center at times like these.”

Among the beneficiaries of its largess is the National Domestic Workers Alliance, which the foundation has been supporting as it seeks to organize home care workers such as house cleaners. The alliance has established an emergency assistance fund, because many domestic workers have lost jobs or are trying to stay home themselves.

“It’s our job to stick with them during those difficult times,” Hayling said.

That hasn’t been a universal response to the letter. Buchanan said that although he’d heard that some foundations were already considering just such a move on their own, others are in outright opposition amid a stock market that tanked and is still off its record high in February.

“Phil, you really don’t get it. We have already taken a big hit and we can’t lock in our losses now. We’ve got to be here for the next crisis in 30 years,” was one type of response Buchanan said he had heard.

The crisis has similarly brought renewed attention to the immense growth of donor-advised funds, a charitable investment vehicle sponsored by traditional public charities, such as the California Community Foundation, but also by independent charitable affiliates of financial services companies. Money is deposited into the fund and disbursed at will by the donor to recipients.

The funds are simpler to establish than a private foundation and have made Fidelity Charitable the nation’s largest grant maker, giving out more than $5.25 billion last year .

But the funds have drawn criticism because they allow donors to take an immediate tax deduction — which can be beneficial if facing a large tax bill — without any disbursement requirement, leading to the warehousing by some of philanthropic dollars. Donor-advised funds have become favorites of the tech community, such as WhatsApp founder Jan Koum, who Bloomberg reported contributed $114 million after selling the messaging service to Facebook.

Antonia Hernandez, chief executive of the California Community Foundation, said that the accusations of hoarding did not apply to her L.A. institution, where annual payouts from donor-advised funds are roughly 15% to 20% and total some $200 million. “Our donors are very generous,” she said.

Nevertheless, the Milken Institute Center for Strategic Philanthropy put out a nationwide call for donors to release money to nonprofits battling the coronavirus, noting a study that found there were 700,000 donor-advised accounts holding an estimated $110 billion nationwide as of the end of 2017.

“Where there is a crisis, there is opportunity to be seized to get more philanthropic capital off the sidelines and put it to work in really smart ways,” said Melissa Stevens, executive director of the center. “Donors have the opportunity — and really the obligation — to do their part.”

Fidelity Charitable has challenged its donors to set aside $200 million in coronavirus-related grant recommendations by May 5, and as of Friday $147 million had been made, according to its website.

But with masses of Americans facing deprivations not experienced in generations — during an era some have compared to the Gilded Age — some of the biggest donors have found themselves the target of barbs.

“When you hear that Jeff Bezos has donated $100 million to food banks during this crisis, remember that Amazon paid just 1.2% in taxes on $13,285,000,000 in profit last year,” tweeted Berkeley professor Robert Reich, a critic of billionaire philanthropy who served as Labor secretary under President Clinton. “The solution isn’t philanthropy. It’s making everyone pay their fair share to strengthen our safety nets.”

Among the highest-profile givers is Bill Gates, while Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey has so far made the biggest pledge, to put $1 billion from his stake in payments firm Square — more than a quarter of his wealth — into a limited liability corporation to fight the outbreak and, later, fund other causes.

One of his first outlays was $2.1 million to the L.A. Mayor’s Fund to help domestic violence victims, who can face physical harm if they must stay at home. Rihanna’s foundation also gave $2.1 million to the cause. The use of an LLC doesn’t confer any tax advantages until money is disbursed, but even so, big donations by him and others in the tech community have been derided.

Journalist Anand Giridharadas, who critiqued billionaire giving in his 2018 bestseller “Winners Take All,” said it was important to understand why philanthropic giving had become so critical — namely public policies and a tax system that benefits the wealthiest and big corporations but has left the nation with meager health, employment and social services compared with other developed countries.

“If you look at why our systems are as precarious as they are in this country relative to other countries ... the biggest culprit is the same billionaire class that is now so publicly heroically stepping up,” he said. “We would not be this bruised if not for the very people masquerading as the help.”

Variations on that sentiment are also shared by members of the giving class. The Open Society Foundations, founded by liberal financier George Soros, donated $130 million globally to provide relief for communities hit hard by the viral outbreak.

“We missed the opportunity to create a more just economy after the financial crisis of 2008 and provide a social safety net for the workers who are the heart of our societies. Today, we must change direction and ask ourselves: What kind of world will emerge from this catastrophe, and what can we do to make it a better one?” Soros said in a statement accompanying the gift.

But prominent philanthropic scholar Una Osili, who leads the research program at Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, believes the crisis has highlighted not just a debate over the role of philanthropy in a polarized society, but also America’s penchant for charity.

That fondness was something French political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville famously observed as far back as the 1830s, and it was rooted, Osili said, in our founders’ conception of a restricted government, leading to a limited safety net and tax policy that encourages charitable contributions. It has made Americans the most generous givers among developed countries as measured by household giving as a percentage of gross domestic product, with total giving reaching $428 billion in 2018, she said.

“It’s not just the large gifts — there is a generosity taking place at the community level by everyday people and sometimes really heroic acts where people are stepping up to help their neighbors,” Osili said of the current response.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.