Why are eggs getting so expensive? Blame coronavirus demand

- Share via

As stay-at-home orders swept across the country, shoppers rushed to grocery stores and stocked up on staples, among them eggs. This surge in demand has boosted egg prices, both nationally and especially in California, and probably will for some time.

On March 2, the Urner Barry wholesale benchmark for a dozen conventional California shell eggs was $1.55. By March 27, the benchmark had risen to $3.66, where it remained for several days before decreasing slightly to $3.26, as of Friday.

That means higher costs for retailers and shoppers. In the last three weeks, grocers’ egg costs increased 57%, said Dave Heylen, spokesman for the California Grocers Assn., which represents more than 80% of the state’s retail grocery stores. A bit of relief came last week, when those costs dropped about 8%.

Northgate González Market is paying more to get eggs on its shelves, up anywhere from 20% to 35%, said Mike Hendry, executive vice president of marketing and merchandising.

He described it as “one of the largest increases we’ve seen in quite a while.”

The chain opted to reduce its margins, passing on only a portion of that cost to shoppers, Hendry said. On Tuesday, the chain decreased its retail egg prices by $1 ahead of an anticipated supplier price reduction.

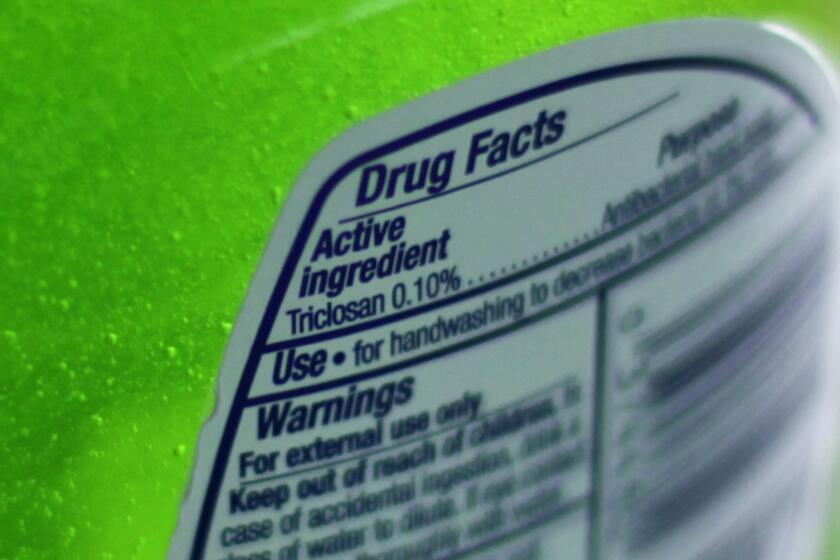

Contrary to viral videos, the FDA says to not use dish soap to wash fruits and vegetables because soap is not meant for human consumption and could make you sick.

Agricultural experts describe the price increase as a lesson in supply and demand. There’s only a fixed number of eggs available on any given day — you can’t squeeze an unlimited number of eggs out of a chicken, and it can take months to buy more hens and build more coops for them. In the meantime, shoppers are buying extra cartons as they aim to limit grocery runs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some retailers have purchased double or even six times their usual orders of eggs, said Brian Moscogiuri, a director at Urner Barry and an analyst covering the egg and egg product markets. To try to keep eggs in stock, some stores posted limits on the number of egg cartons customers could buy.

That’s the case at Beachwood Market in the Hollywood Hills, where owner Alex Papalexis said he had to limit customers to one carton per household.

“People were scrambling, no pun intended, to get eggs,” he said.

He, too, is paying more for eggs, an additional 50 cents to 75 cents per carton, depending on the type. Though he hadn’t yet raised prices, Papalexis said he probably would soon.

He noted that many restaurants and hotel kitchens are closed, meaning eggs destined for diners’ dishes could now be diverted to store shelves.

If you have extra food, here’s how you can help local food banks or pantries. If you are struggling to buy food, this guide has information for you.

“There’s a question there,” Papalexis said. “Why would they have to raise their rates?”

Laws prohibit price-gouging in California during a declared state of emergency, capping price increases for essential goods at 10% compared with their pre-crisis costs. Exemptions, however, exist should the cost of a product increase along the supply chain — to compensate should shipping or labor costs rise.

The rules are hard to enforce, said Diana Winters, assistant director of the Resnick Center for Food Law and Policy at the UCLA School of Law.

The state attorney general’s office relies on consumer complaints to ensure essential items, such as food, don’t exceed that 10% price-gain cap, she said.

Prices for eggs certainly have risen more than 10% in many markets, but it’s hard to gauge all of the factors that might contribute to that increase, Winters said. For example, restaurant closures could mean egg producers need to divert their supply to grocers, and that change in distribution and additional packaging comes with a cost.

“Eggs are naturally, very often, one of the most price variable products in the supermarket,” said Daniel Sumner, UC Davis professor of agricultural economics and director of the UC Agricultural Issues Center.

Jesse Laflamme, chief executive of New Hampshire-based Pete and Gerry’s Organic Eggs, said his freight costs have gone up since the coronavirus pandemic because there are not enough refrigerated trucks to transport all of the fresh goods now in high demand.

His company has also slowed its egg packaging equipment and spaced people out to comply with social distancing directives. The company chose to absorb the extra costs rather than increase prices. Its eggs are not priced on the wholesale egg market.

“Being a commodity market, it’s really sensitive to any supply or demand fluctuation within single percentage points,” Laflamme said.

Egg prices could remain elevated for at least a few months, Sumner said. And the demand for eggs has been historically strong during tougher economic stretches. Eggs are a relatively cheap source of protein and aren’t seen as a luxury food item.

“It may take longer to get back to normal for the egg business,” he said. “We can build supply, but it takes a few months.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.