How to protect workers from the coronavirus: This CEO has good advice

- Share via

When Kevin Kelly woke up March 11, he glanced at his phone, saw a stock market in free fall and gently shook his head. “Overreaction,” he thought.

“I was a skeptic. The idea of a global pandemic seemed unfathomable,” said Kelly, chief executive at Emerald Packaging, a manufacturer of plastic wraps and bags for fruits, vegetables and snacks his family owns in Union City, southeast of San Francisco.

He’d change his mind on his 25-mile commute to Emerald’s factory. On the radio, disease experts spoke about the seriousness of the pandemic and about the lack of preparation in the United States.

The key to Kelly’s attitude shift were the words of Scott Gottlieb, former U.S. Food and Drug Administration commissioner. Kelly pays close attention to the FDA, given the business he’s in, and said he’s always respected Gottlieb’s opinions. When Gottlieb mentioned Northern California as an emerging hot zone, Kelly knew it was time to get serious.

“He said we were at a tipping point and if we didn’t take mitigation steps we would be facing a very large epidemic,” said Kelly, 58. “The night before, Trump had given a speech that left me with the sense that we had to take action ourselves because he sounded so helpless.”

Kelly sped up the car, reached Emerald, hustled inside and ordered everyone to keep away from the meeting room for their regular 10 a.m. staff meeting. They should stay at their desks and workstations, he said, and pick up their phones, because the meeting would be held by conference call.

“We have to start social distancing, because if we don’t, people are going to get sick,” he told them.

Thus began three days of rapid planning and new, strict rules on cleaning, hygiene and personal interaction to keep the virus at bay.

Emerald would later be labeled as an essential business under government exemption, allowed to stay open while most businesses closed. Its plastic wrap and bags protect food from sneeze droplets, fingertips and other means of transmission. If you see plastic bags filled with salad, or cut fruit or vegetables, there’s a good chance they were made by Emerald. The company also makes thicker bags for potato chips and other snacks.

(Full disclosure: I worked with Kelly at Businessweek magazine three decades ago.)

The pandemic actually has boosted business for Emerald, which posted revenues of around $85 million last year. Bookings are up three times over a year ago, Kelly said.

The popular Japanese and Hawaiian diner at Gardena Bowl has seen business decrease by half since the coronavirus shutdown began.

But he felt torn. “By staying open,” he asked himself, “am I making everybody sick?”

The best approach, Kelly decided, was to make Emerald’s office and manufacturing operations as safe as possible for its 250 employees.

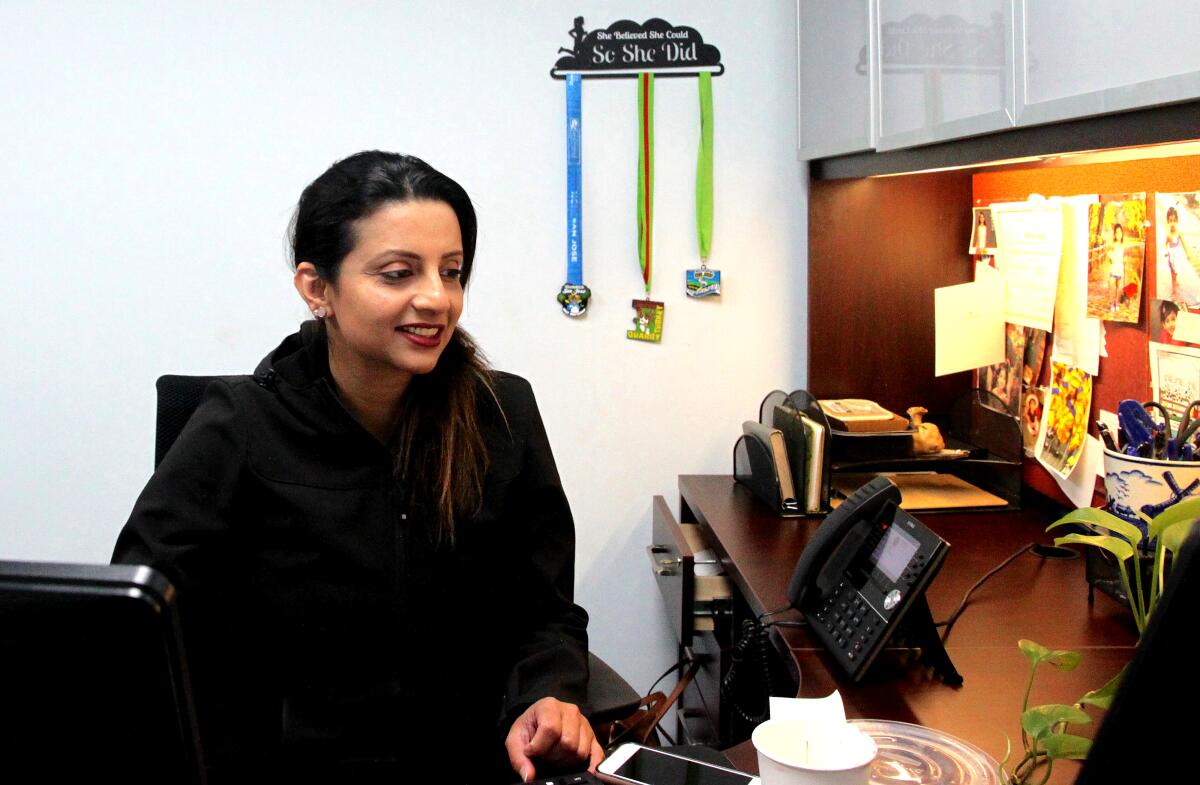

Working with Pallavi Joyappa, the company’s chief operating officer, and other company leaders, Emerald went into battle mode.

Gatherings of more than five people were banned, and six-foot-minimum physical distancing was required. Larger meetings would be held outdoors.

Lunch and breaks were staggered, no more than five employees at a time. Tables were spread apart.

A two-level sanitizing protocol was announced, one for employees, one for equipment. The print shop is always stocked with isopropyl alcohol, “drums of it,” Kelly said. It was diluted, put in spray bottles, and handed out for each desktop and factory workstation.

Starting with President Trump, the GOP is calling to put millions at risk of contracting coronavirusso the stock market recovers.

Kelly called a niece, a graduate student in public health, who helped with the hand-washing protocol: arrive at work, wash hands, punch in on the time clock, wash hands. Use alcohol spray to wipe down high-contact workstation areas at the beginning and end of each shift, never mind that someone had just done it.

“We figured different people would [tend to] wipe down different parts,” Kelly said.

Kelly woke up one night gripped with anxiety about unwiped handrails, lockers, doorknobs. Two cleaners were hired for each shift to do nothing but keep surfaces clean.

Not everyone got the message. Kelly and Joyappa came in the following Sunday for a surprise inspection. In one area, the spray bottles stood empty. Nobody had taken responsibility for refills.

At a staff meeting, Kelly reiterated his insistence that anyone sick must stay home. One guy put his hand up and asked, what if he was the only one who could operate a machine and it went down?

“I looked at him and said, ‘Don’t … f—ing … come … in,’ and had him repeat it,” he said. “Everybody laughed, but they got the message.”

The company has added two weeks to its regular 40-hour paid time off policy. “But if someone gets the virus it is totally open-ended. No one will lose their job, raise or seniority” if they’re infected, Kelly said.

Emerald sells its products around the world. Employees who had come back from an international trip were told to self-quarantine for 14 days. Office workers in purchasing and customer service departments received instructions to work from home, a culture shock.

“For a factory like us, this whole work-from-home concept is difficult,” COO Joyappa said. “We have people running back and forth to the factory to see how things are going.”

The company suddenly had to look at using Zoom, Webex, Skype or Slack, or some combination of collaboration software. Its two information technology staffers, Irina Anikieva and Steven Kokal, took only eight hours to have a system up and running for the 10 employees working from home.

By March 16, a seven-county Bay Area “shelter in place” had been ordered, with only “essential” businesses allowed to stay open. The federal government’s critical infrastructure list, recommended as a guide by Gov. Gavin Newsom, counts companies such as Emerald as essential, Kelly said.

He had staff type up letters, print them and hand them out to employees to show to police if they were stopped while driving in. Truck drivers delivering goods received similar letters. Truckers were also asked not to step inside the building and to wash their hands before handing over paperwork and unloading cargo. Sinks were set up at the loading dock.

While all this was happening, the factory had to re-gear for a dramatic change in product mix.

“It’s shifted radically,” Kelly said. “No packaging for food service like restaurants or catering companies and a total switch to retail, with more complicated graphics to appeal to consumers, which takes longer to print. Food service packaging went from 10% of our sales to zero overnight.”

Now that Emerald is reaching operational equilibrium, Kelly and Joyappa are planning to make the rounds through their industrial park, introduce themselves to other companies, and offer to talk about ways to share resources.

Emerald is trying to help a favorite local restaurant stay alive — eating choices around the park are limited. “The restaurant is dying, so we ordered 270 burritos and chips,” Kelly said. Emerald employees will get a free lunch once a week.

Southwest and American Airlines cut back on food and drinks on flights

Aware that Emerald’s products may be in far higher demand than goods from some other essential businesses, Kelly advises others to do everything possible to preserve cash — he believes the pandemic and recession will last far beyond Easter Sunday, and the need to take care of employees and meet fixed expenses will continue even when revenue falls.

Another rule: “Don’t trust your banker,” he said. Banks may seem friendlier amid the crisis, but they will cut off your cash as soon as they find it necessary, he believes. His advice: Keep cash at one bank, loans at another, and transfer cash funds to new accounts as needed.

He also advises against dangling bonuses to those who show up for work, as one business friend told Kelly he’d done. “Talk about moral hazard,” he said — that only encourages sick people to infect the healthy. Best to take care of sick employees but keep them away, he said.

Kelly believes that bosses who tell people to report to work should show up themselves. He could do much of his work from home, he said. He is married with two kids in college, one in high school. “But I’m the captain of the ship. There’s a moral obligation to be here.”

But he has little patience for those, including President Trump, who have speculated about a rapid relaxation of strict social separation orders.

“It would be foolish to send people back to work without knowing disease spread. We could be bringing people back only to make them sick or kill them,” Kelly said.

“It’s easy for Trump and [ex-Goldman Sachs Chief Executive Lloyd] Blankfein to suggest these things when they’re not on the front lines. They’re like generals in the First World War: send the troops over the top only to get them maimed and killed.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.