Column: Some employers are doing the right thing in the coronavirus crisis. Some aren’t

- Share via

Tip a hat to Darden Restaurants, the owner of Olive Garden, LongHorn Steakhouse, and other casual sit-down chains. The company announced last week that it had implemented a paid sick leave policy for its 190,000 employees, including a starting balance for those with at least six months of employment.

Now cast a gimlet eye in the direction of Richard Branson, whose Virgin Atlantic is asking its 10,000 employees to take eight weeks of unpaid leave over the next three months in an effort to “drastically reduce costs without job losses.” (Virgin Atlantic is losing money, but Branson’s net worth is more than $4 billion.)

Or Whole Foods CEO John Mackey, who last week reminded his workforce that they can “donate” their paid time off balances to co-workers facing medical emergencies. Mackey’s email generated a demurral from Amazon, which acquired the grocery chain in 2017, to the effect that Mackey’s policy predated the acquisition.

We’ve been living off the formation of low-wage and low-hour jobs in sectors that happen to be incredibly vulnerable to just this particular crisis.

— Daniel Alpert, Cornell Law School

Whole Foods workers, like all other Amazon employees diagnosed with COVID-19 (the disease caused by the novel coronavirus) are subject to Amazon’s recently announced policy granting them up to two weeks of paid time off, the parent company said.

Those examples merely hint at the range of responses that employers have made to the prospect that large numbers of their workers may have to spend days off the job or in quarantine — whether self-imposed or mandated — to fight the coronavirus pandemic. Some employers are stepping up with liberalized paid sick leave policies. REI and Patagonia, which have long been known for good customer relations, which have temporarily closed their retail stores and are continuing to serve customers online, have said their store employees will continue to be paid during the shutdowns.

Others are doing so begrudgingly. And still others may not be doing much at all.

The overall picture is one of extreme fragility for millions of American workers, especially at consumer service companies.

This reflects a trend that has been developing for more than three decades.

By limiting sick leave and free healthcare, the U.S. system will promote the spread of coronavirus.

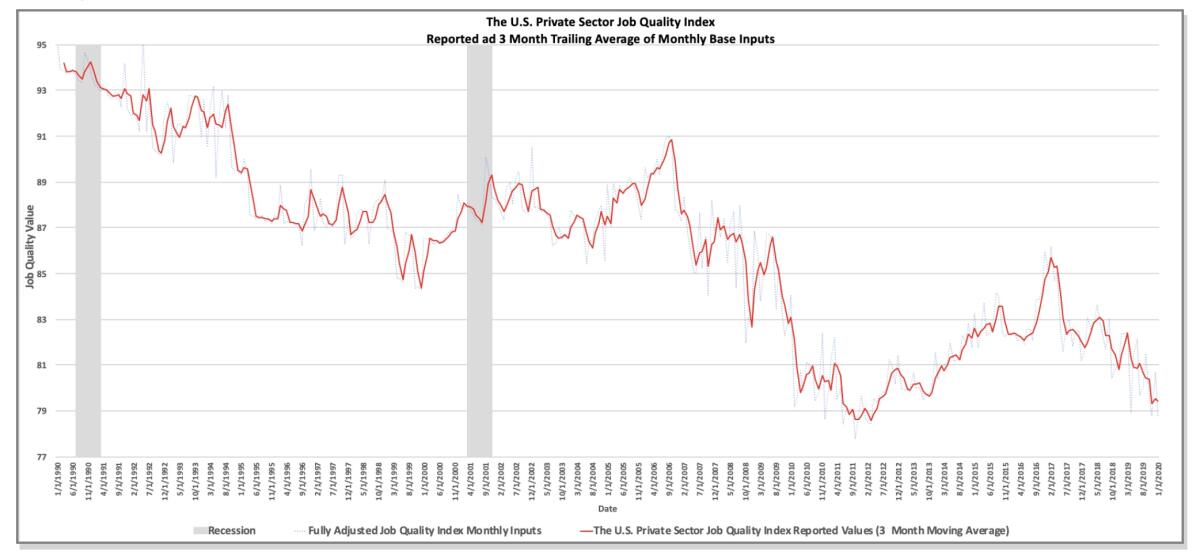

“We’ve been living off the formation of low-wage and low-hour jobs in sectors that happen to be incredibly vulnerable to just this particular crisis,” says Daniel Alpert, an investment banker and adjunct professor at Cornell Law School who helped develop the Job Quality Index, which tracks the relative rise of private sector jobs paying less than the average weekly income of all American production and nonsupervisory jobs.

“In the current situation, where you have a dead stop in consumer activity, any ‘customer-facing’ business where the customer is no longer doing any ‘facing’ is under enormous threat,” Alpert told me.

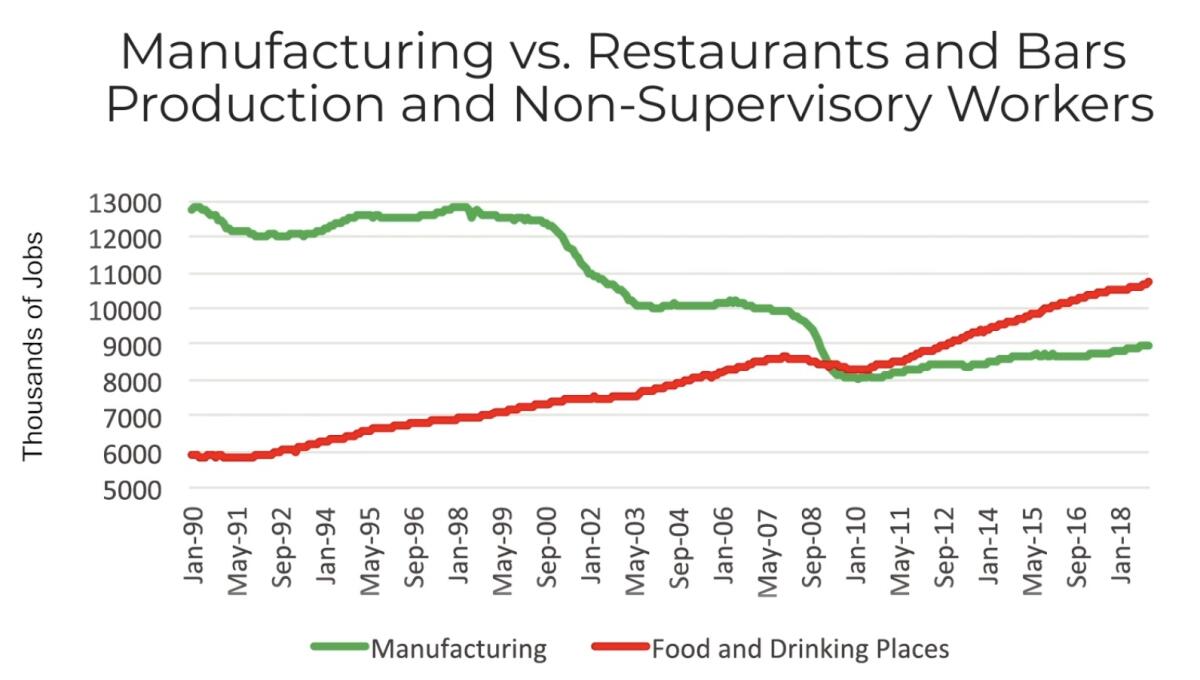

The increase in consumer service jobs that Alpert and his colleagues track is the mirror image of the decline in manufacturing employment; his figures show that employment in restaurants and bars began to exceed that in manufacturing in late 2009, and never looked back. In 1990, the 12.7 million manufacturing jobs accounted for 17.3% of all rank-and-file workers. Today they’re down to 9 million jobs and 8.5% of the rank-and-file workforce.

Service sector workers are not only low-paid and granted fewer hours than higher-paid and goods-producing workers, but their weekly schedules are far more volatile than traditionally.

“There’s been a shift to just-in-time scheduling,” says Daniel Schneider, a UC Berkeley sociologist who is a founder of the Shift Project, which collects data on scheduling practices from thousands of retail workers employed by large firms. “Their business model is one of part-time instability, in which workers get scheduled at the last minute and have to remain on-call.”

That presents a challenge to the traditional social safety net, Schneider says. Many safety net programs, including food stamps, impose work requirements on enrollees. “Volatility of work makes reporting hours very difficult.”

The vast majority of these workers aren’t the proverbial “gig workers,” such as Uber and Lyft drivers, who are treated as non-employees with virtually no employment rights. Most get paychecks from employers, including major corporations, Alpert observes.

That doesn’t make their work schedules necessarily secure, however. Many are victimized by a nearly 50-year trend in which major corporations have shed their responsibilities to their frontline workers.

President Trump took credit for the healthcare business doing what it would do anyway.

Taco Bell, for example, has announced that at its company-owned restaurants, it will continue paying employees who are required to stay at home or who work at a location that has been closed, for their regularly scheduled hours. It said it is “actively working with our franchise partners to encourage a similar approach.” But more than 4,600 of Taco Bell’s 6,000 restaurants are franchisee-owned.

Darden’s sick pay policy applies to its 1,799 restaurants in the U.S. and Canada, but not to 80 franchised restaurants in the U.S. and abroad, the company told me.

McDonald’s says its full- and part-time employees can earn up to five sick days per year and says it will pay corporate-owned restaurant employees who are “asked to quarantine” for up to 14 days off from work. (The company didn’t specify whether these were workers ordered to be quarantined or self-quarantined because of contacts with or caring for infected persons.) But those policies cover only the 205,000 workers at its corporate offices and company-owned restaurants. The vast majority of McDonald’s locations — 36,000 out of the nearly 39,000 restaurants worldwide, employing an additional 200,000 workers or more — are franchise operations that can set their own workplace policies.

McDonald’s, as it happens, has been a powerful opponent of policies that would hold franchise parent companies such as itself responsible for pay and workplace conditions at its franchise locations. Unlike the Obama administration, which moved toward those policies, the Trump administration has blocked them.

Many companies that have liberalized their sick leave policies still impose conditions that could discourage workers exposed to the novel coronavirus from staying home, at risk to their colleagues and customers. Amazon’s grant of up to two weeks paid time off applies to “employees diagnosed with COVID-19 or placed into quarantine.” Hourly workers are entitled to unlimited time off through the end of March — unpaid.

Plainly, the realities facing frontline service workers make a payroll tax holiday, which is strongly favored by President Trump, virtually useless; workers laid off or saddled with steep cutbacks in hours pay little or no payroll tax, which is levied at the rate of 12.4% for the first $137,700 of wage income this year, split evenly between employer and employee. For a minimum-wage worker notching 20 hours a week, that’s as little as $8.99 a week.

Workplace advocates and some members in Congress are talking instead about a “helicopter drop” of cold hard cash, akin to the one-time government checks of up to $1,200 for married couples, including $300 per child, issued in 2008. The payments were phased out starting with household income of $150,000 (for couples), but even low-income households that owed no federal tax were eligible for at least $300, provided they earned at least $3,000 during the year.

A payroll tax cut was a bad idea in President Obama’s time, and even worse now.

Political decision-makers will have to see these payments in terms that differ from the financial crisis of 2008. “Helicopter money has always been a way of spurring consumption to come out of a recession,” Alpert says. “This is different — this is money to ensure survivability.”

What may emerge from the coronavirus crisis is a new, or at least restored, approach to the employment relationship by government and the private sector. Alpert points to the epochal change in the 1930s, when the New Deal brought government firmly into society as an economic mediator. The New Deal gave government the authority to set the minimum wage, outlaw many workplace abuses, and grant workers new rights to unionize.

Many of those gains were reversed after 1980 and the advent of the Reagan administration, which aimed to shrink government and started the trend toward punching holes in the safety net, removing regulations applying to employers and inspiring them (largely through the breaking of the air traffic controllers strike) to take a harder line against unions.

That approach is still visible in the coronavirus bill crafted by the Democratic House majority and awaiting consideration by the Republican-controlled Senate. Even Mitt Romney, not ordinarily known as a friend of the working class, has proposed issuing an immediate one-time $1,000 check to every American. The measure’s mandate for paid sick leave exempts big employers — those with 500 workers or more — and allows small employers to seek hardship exemptions.

“We should be putting big companies on the table,” Schneider says. He’s right. Nothing has shown the necessity of a sea change in how we safeguard the livelihoods of our most vulnerable workers as the condition we’re in today.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.