ICYMI: If Trump thinks he can get more than 3% economic growth, he’s dreaming

- Share via

Annualized economic growth for the fourth quarter of 2019 came in at a modest 2.1%, according to the government’s Bureau of Economic Analysis.

In figures announced Thursday, the BEA also pegged growth for all of 2019 at 2.3%, down from 2.9% the year before. The latest statistics are designated by BEA as “advance” figures, subject to two revisions in coming months as more precise readings from economic components come in. Typically, the revisions aren’t large.

Thursday’s figures didn’t surprise economists, who were expecting something in those neighborhoods. But they underscore how overly optimistic President Trump and his economic team were of the prospects for economic growth. They consistently forecast growth of better than 3% a year. They’ve never gotten it.

Some quarters have shown better than 3% growth on an annualized basis, but that’s not the same as annual growth since it hasn’t extended for a full year or even four straight quarters.

We examined why Trump’s expectation was a pipe dream in a column published on May 19, 2017. The column has stood the test of time so far, and we reproduce it below.

======================

With the political world deeply focused on the question of whether the Trump administration comprises a gang of Russian pawns, less attention has been devoted to more mundane questions, such as what ever happened to Trump’s economic policy?

As it happens, economists are keeping their eye on that ball, and their conclusion is that it’s in a bad way. More specifically, they recognize that Trump’s policy is aimed heavily at achieving annual economic growth of more than 3%.

During the presidential campaign, Trump promised growth of 3.5% a year, and sometimes even 4%. There’s no disagreement that a sustained growth rate of this magnitude would be a significant achievement. Over the past decade, the economy has grown at an average of about 2% a year. The Congressional Budget Office forecasts an annual average of about 1.9% well into the next decade.

The U.S. hasn’t had sustained real annual growth (that is, over inflation) of better than 3% since the 1990s, with a brief spurt in 2004 and 2005. Making up the difference from 2% to more than 3% looks like a pipe dream.

High rates of growth, and the productivity that drives it, are likely distant memories from a bygone era.

— Bill Gross, Janus Capital

This sentiment crosses ideological lines. It’s shared by Jason Furman, formerly the chief economist for the Obama White House (“it would require everything to go right … in ways that are either historically unparalleled or toward the upper end of the historical range”) and Edward Lazear, who served the same role for George W. Bush (“pray for luck,” he advises).

Then there are the nonpolitical observers, such as bond guru Bill Gross, who says: “High rates of growth, and the productivity that drives it, are likely distant memories from a bygone era.” And academic economists such as Northwestern’s Robert J. Gordon, who states bluntly in his pessimistic book “The Rise and Fall of American Growth” that U.S. GDP’s best years are behind it.

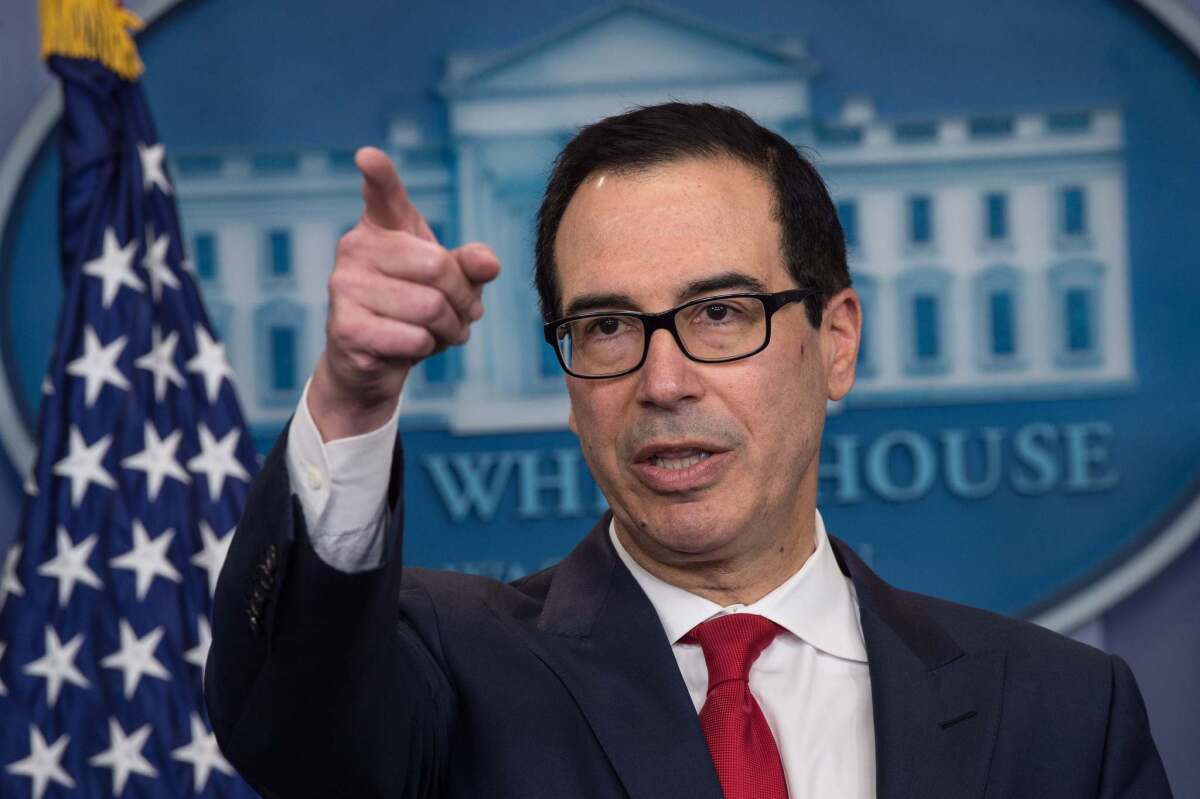

In fact, the only place one can find confidence about a growth rate of 3%-plus is inside the Trump administration, where Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin says it’s “very achievable.” But he would say that, wouldn’t he? After all, Trump’s economic doctrine is dependent on it. Without such growth, Mnuchin’s promise that the Trump-backed tax cut would “pay for itself” is a fantasy.

Let’s stand in the headwinds and see how they look. They fall into four categories: demographic, historical, technological and Trump-centric.

Gross domestic product growth comes from two main sources, as Chad Stone of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities explains: growth in the labor force and growth in productivity. Trump maintains that he can improve on the first because — so he claims — Obama economic policies threw millions of Americans out of work.

But unemployment statistics suggest instead that there isn’t much slack in the workforce. At 4.4%, the unemployment rate is at about the point economists judge to be full employment. It’s true that the labor participation rate — the share of working-age persons with jobs — is at a mere 63%, down from 66.4% in January 2007, but the aging of the U.S. population leaves little hope of reversing the trend line.

The most recent increases in the workforce occurred in the 1970s through the 1990s, with the entry of baby boomers and women. But the baby boomers of both sexes are retiring now. According to the Pew Research Center, unless immigration takes up the slack by providing 18 million more workers, the U.S. workforce will continue to shrink at least through 2035.

What are the prospects for that surge of immigration? Dim, obviously, as long as Trump’s hostility drives policy.

That places the onus on productivity growth. Productivity, defined as real output per hour of labor, is unlikely to pick up to the degree necessary to jolt economic growth above 3% for the long term.

From 2008 through late 2016, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. was mired in a productivity slump averaging growth of 1.1% a year. That’s a pittance compared to the postwar average of 2.3%; the last high point was reached in 2001 through 2007, when growth averaged 2.7% a year.

Economists are a bit perplexed by the productivity slowdown, especially since it seems to be afflicting all industrialized economies at the same time. Indeed, the U.S. is doing better than most. Northwestern’s Gordon maintains that it’s the result of a secular end to a long technological cycle — that the low-hanging fruit of innovation-driven gains has been picked: the first industrial revolution, air conditioning, automobiles, computers and communications and the replacement of small stores by big-box chains.

Gordon is skeptical that the touted revolutions beckoning around the corner will add much to productivity. He contends that the potential of robots, artificial intelligence, big data and driverless cars has been oversold or already baked into the existing economy.

He also warns of a major headwind: rising inequality. The decline in the standard of living resulting from skewing economic rewards toward the top will result in an overall slowdown of economic growth, he says. It’s proper to observe that many economists and technologists consider Gordon to be unduly pessimistic, but there’s scarcely any question that he’s put his finger on some evident trends.

The last factor is the drag on growth of other Trump policies. Deregulation could spur short-term improvements in some industries, but on the whole, it threatens to create costs — the consequences of dirty air and water or of an increase in the uninsured don’t come cheap. And even the most sedulous fans of deregulation, such as Douglas Holtz-Eakin of the American Action Forum, don’t forecast additions to economic growth of more than a few hundredths of a percentage point a year. That won’t get Trump much closer to 3%-plus.

With economists being cautious to their bones, few will say categorically that reaching Trump’s goal is impossible. But he’s placed a lot of weight on the shoulders of that goal and produced precious little evidence to show it can be achieved. The general consensus seems to be: it could happen, but that’s not the way to bet.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.