Trump makes wage-theft lawsuits harder — but not in California

- Share via

Say you’re a company that hires a janitorial staffing agency to clean your offices or a security firm to patrol your parking lot.

Say you’re a retailer that relies on outside truckers to deliver your goods.

Say you’re a general contractor who hires drywall and electrical subcontractors.

Are you responsible if those workers are paid less than minimum wage and denied overtime?

The Trump administration Monday loosened the federal government’s “joint employer” rule for businesses that contract out work, making it harder for victims of wage theft at staffing agencies and subcontractors to sue companies where the violations take place. The rule also frees franchising companies from responsibility for working conditions at their franchises.

The new policy overturned a 2016 Obama administration rule that had broadened workers’ ability to put companies on the hook for shorting paychecks. The Trump policy, which prompted 60,000 public comments after it was proposed last spring, was hailed by business groups and assailed by workers’ rights organizations.

But the new rule will have no effect on California businesses because “our laws are more protective” of workers, according to California Labor Department spokeswoman Crystal Page. And California labor laws are not preempted by the federal Fair Labor Standards Act, under which the Trump rule was issued.

“The definition of employer in California is broad enough to reach any person, company or agency who directly or indirectly employs or exercises control over an employee’s wages, hours or working conditions,” she added.

UC is at war with its biggest labor union. University employees fear they will be displaced by lower-paid temp workers

California has the country’s strongest wage and hour laws, with a higher minimum wage and a lower threshold for overtime than federal law, noted Tia Koonse, a research manager at the UCLA Labor Center.

“Most workers wouldn’t sue under [federal law] because they’d recover more money using state laws,” Koonse said. “So this new federal rule doesn’t have any practical impact. California is the envy of other states for its protections for precariously employed workers.”

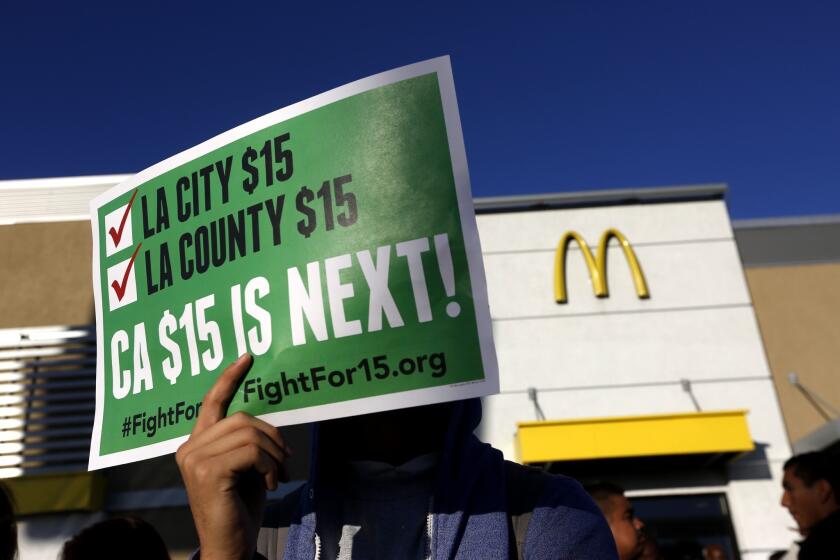

In the case of franchises, the Trump administration’s joint employer law does not affect California for a different reason. The state’s jurisdiction over franchises was limited by an October 2019 court decision. Some 1,400 workers sued McDonald’s Corp., alleging that its franchisees denied them overtime, meal and rest breaks. The U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the company was not a joint employer responsible for franchisee violations under California law.

In a separate case in December, the National Labor Relations Board, with a Trump-appointed majority, also reversed an Obama joint employer rule. It gave 20 franchisee workers, who were fired for organizing, a back wages settlement of $171,636, but declined to impose joint liability on McDonald’s.

Despite California’s exceptionalism, Trump’s new policy could have broad effects across the U.S. labor market at a time when corporations such as McDonald’s, Amazon and Comcast have faced lawsuits arguing the companies are jointly responsible, along with third-party contractors, for unpaid minimum wages and overtime.

By some estimates, more than 13.8 million U.S. workers are employed by staffing agencies, subcontractors and franchises. “Our economy has changed dramatically since the 1980s,” said David Weil, former administrator of the Labor Department’s Wage and Hour division under Obama and author of “The Fissured Workplace,” a book about the transformation of the labor force. “In many industries workers’ pay and job conditions are affected by multiple employers. The concept of joint employment is critical.”

Trump’s new policy, which takes effect March 16, establishes a four-part test to determine whether a company is a joint employer, but the weight given to each factor will vary depending on the circumstances. The factors are:

- Whether the company can hire or fire the employee.

- Whether it supervises the employee’s work schedule.

- Whether it sets wages.

- Whether it maintains employment records.

The Obama administration’s joint-employer policy took into account several other issues, such as the nature of the work performed and whether the work involved a core part of a company’s business.

Weil characterized Trump’s new policy as “an interpretive rule, closer to a form of administrative guidance, and not a full-blown regulation. It does not change the basis for courts to rule on joint employment.” But he added it suggests the administration will pull back on enforcing joint employment issues.

In announcing the decision, U.S. Labor Secretary Eugene Scalia said the rule “furthers President Trump’s successful, governmentwide effort to address regulations that hinder the American economy and to promote economic growth.”

Robert Cresanti, president of the International Franchise Assn., which had lobbied hard for the change, said it offers “much-needed clarity for the 733,000 franchise establishments across America.”

For California businesses, 2020 will be a year of reckoning. Sweeping new laws curbing long-time employment practices take effect, aimed at reducing economic inequality and giving workers more power in their jobs.

However, the Economic Policy Institute, a Washington-based labor think tank, said the new policy “creates an incentive for large corporations to outsource work to staffing companies or subcontractors and escape responsibility … for complying with basic workplace protections.”

It added, “Employers refusing to pay promised wages, paying less than legally mandated minimums, failing to pay for all hours worked, or not paying overtime premiums deprives working people of billions of dollars.”

Workers at temp and staffing agencies and at subcontracting firms earn less than the same workers who are hired directly by companies, EPI noted. According to EPI’s comments on the rule, that lost income amounts to $955 million a year, and wage theft accounts for an additional $138 million.

Beyond its general joint employer law, California has adopted alternative approaches to enforcement. A 2018 law, aimed at the 13,000 truck drivers who service the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, holds retailers such as Target, Home Depot and Amazon jointly liable for wages that subcontracted trucking companies fail to pay.

Another 2018 law requires construction subcontractors to share information on wages with general contractors and allows general contractors to withhold payments from subcontractors who refuse to cooperate. The law authorizes civil suits against general contractors who oversee cheating subcontractors.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.