California businesses breathe sigh of relief over deal to update NAFTA trade pact

- Share via

There is little overall difference between the old North American Free Trade Agreement and the Trump administration’s replacement. But California businesses are just relieved to finally have some certainty they can plan around.

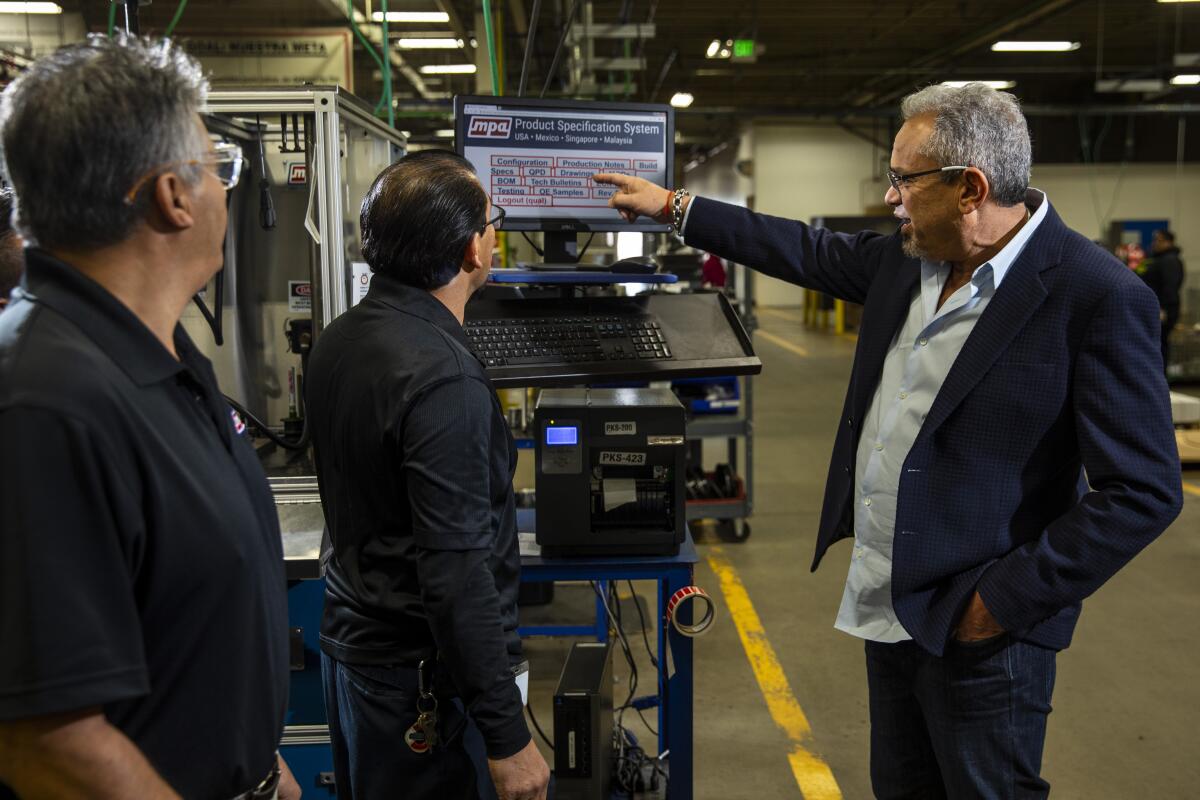

Selwyn Joffe, chief executive of a Torrance auto parts manufacturer, had 3,000 workers in his Tijuana factories and was all set to add hundreds more this year. As he listened to President Trump, though, he got cold feet. Even as U.S. trade officials were renegotiating the 1994 agreement, which slashed tariffs among the U.S., Canada and Mexico, Trump continued to excoriate NAFTA as “the worst trade deal” ever made, threatening to kill any new treaty that failed to give the U.S. a “fair deal.”

“We felt it would be a bad thing to abandon NAFTA,” said Joffe, whose company, Motorcar Parts of America, has $493 million in annual revenue. “We didn’t know where things were going. So we slowed down our capital investments.”

But now that the administration and congressional leaders have reached a deal on the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement — known as USMCA or NAFTA 2.0 — Joffe’s expansion, delayed for some four months, will move ahead in January with 400 new workers in Tijuana and an additional 40 in Torrance.

When President Trump unveiled plans to launch a trade war with China early last year, Marisa Bedrosian Kosters, an executive at an Anaheim-based ceramic tile and stone retailer, sprang into action.

The California economy has long depended on the flow of products and services, investments and people across borders, driving innovation and growth. The expected approval of the new pact, by the House on Thursday and by the Senate next year, has calmed the fears of many Golden State businesses.

“From a macroeconomic perspective, USMCA is not a game changer,” said Jock O’Connell, a California trade expert for Beacon Economics. “But trade and especially investment among the three nations has been slowed the last three years by anxieties over the fate of NAFTA.”

Mexico is the Golden State’s top export market with $30.7 billion in goods, led by computers and electronics, accounting for 17% of exports last year. At the same time, California imported $44 billion in goods from Mexico, led by transportation equipment, mainly finished vehicles.

Canada is the state’s second-largest export market, accounting for $17.7 billion in goods, led by computers and electronics, accounting for 10% of the state’s exports last year. California imported $27 billion in goods from Canada, led by transportation equipment.

Much of California’s export trade to Canada and Mexico involves components shipped to multinational operations that manufacture for export to the U.S., O’Connell said.

That’s the case for Joffe’s company, a player in the $135-billion auto aftermarket sector. “We take old alternators and starters from the U.S. to Mexico, and we re-manufacture them to their original state,” he said.

“Without a regional North American agreement, we would be handicapped in competing with China where labor rates are significantly lower,” Joffe said. “The incentives China gives to its manufacturers are greater than anywhere.”

Roy Paulson, president of Paulson Manufacturing, a Temecula company that makes firefighter goggles, is among those expressing relief. “We didn’t know whether we would get a new agreement if NAFTA was taken away,” he said. “Uncertainty is a killer in business.”

Paulson, a board member of the National Assn. of Manufacturers who served on a subcommittee of President Obama’s Export Council, makes all his equipment in California. But his 150-employee operation is indirectly affected by the new agreement since he sells to companies with Mexican operations.

With USMCA, he said, “We are finally making progress after a long period of stasis.”

Here’s how the trade deal plays out in several key sectors of California’s economy:

AUTOS

One reason for the long delay was congressional Democrats’ insistence that the deal negotiated by the Trump administration needed stronger protections for U.S. workers who have seen their factories close and move to Mexico for cheaper wages.

The new agreement may help some American workers, particularly in the auto industry. To qualify for duty-free benefits, carmakers must increase the amount of North American content. And at least 40% of a vehicle’s value must be made by workers who earn at least $16 an hour.

But although that wage floor could mean fewer auto jobs migrating to Mexico where pay is far lower, it may be of scant benefit to Golden State manufacturing.

Ford, General Motors and Chrysler once ran California assembly plants in California, but only Tesla has an automobile factory in the state today, in Fremont. Tesla makes its own battery packs and electric motors and stamps its own body parts, so its cars easily fulfill local content requirements. Analysts say any impact on the company would be minimal.

California wineries were expanding into China’s big wine market. Trump’s trade war is destroying their plans.

At least a dozen auto parts manufacturers are California-based, according to ELM Analytics, a Michigan data firm. And California exported $1.6 billion in vehicle parts to Mexico last year. But some companies such as Motorcar Parts of America, which pays Mexican workers $5 an hour, are unaffected by the wage floor because they sell to consumers, not to automakers.

The AFL-CIO, which has historically opposed trade pacts that make it easier to export U.S. jobs, endorsed USMCA. Besides the auto-related provisions, new language in the pact offers support for independent unions in Mexico, where labor organizers can easily be fired for trying to bargain over wages and working conditions.

“For the first time, there truly will be enforceable labor standards — including a process that allows for the inspections of factories and facilities that are not living up to their obligations,” labor federation President Richard Trumka said in a statement.

But the United Auto Workers is lukewarm toward the pact, noting “much more work remains to fight against the offshoring of jobs and the economic inequality that has plagued our country.” It called for ending bad tax laws that reward companies for moving jobs abroad.

AEROSPACE

One California industry deeply affected by NAFTA is aerospace. The 600,000-member International Assn. of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAM), the nation’s largest aerospace union, estimates some 40,000 aerospace jobs have moved to Mexico in the 25 years since NAFTA was enacted, many of them from the Golden State.

California aerospace jobs declined from 216,000 to just over 75,000 during those three decades. With wages averaging $3 an hour, Mexico lured some 300 foreign aerospace manufacturers. And the industry, now the third-largest in Mexico, became a major exporter to the U.S.

“The outsourcing of U.S. jobs to Mexico will continue at an alarming rate under USMCA,” IAM President Robert Martinez wrote in a letter urging Congress to reject the pact. He called for “stronger rules of origin that do not leave out major sectors of manufacturing.”

In San Diego, Jason Fletcher, an official with a San Diego IAM local, negotiated the 2018 layoffs of the last 265 sheet metal workers at UTC Aerospace Systems’ Chula Vista plant, as the company expanded in Mexicali.

In the 1990s, the factory employed close to 15,000 people, making engine parts for customers such as Boeing and Airbus. But the big aircraft manufacturers demanded lower prices from UTC, forcing the company to move jobs outside California, he said.

“Watching those guys who have homes and families walk out of the plant — it was terrible,” said Fletcher, a former mechanic at a now-shuttered Pratt and Whitney plant. “We scratch and claw to keep work in the U.S. but we see trucks driving around San Diego plastered with ads welcoming aviation companies to Mexico with low wages and tax shelters.”

The Aerospace Industries Assn., a Washington-based trade group, did not respond to questions about offshoring. In a statement, it applauded USMCA as a pact that “will reduce uncertainty, help secure market access for goods.”

“The U.S. aerospace and defense industry depends on strong relationships with Mexico and Canada to build on our nearly $90-billion trade surplus, drive innovation, grow manufacturing in America, and support more than 2.5 million U.S. jobs,” it said.

PHARMACEUTICALS

One California industry that had hoped for relief from USMCA didn’t get it.

Trump’s original draft, signed with Mexico and Canada last year, granted at least 10 years of protection from generic competitors to biologics, a class of drugs made from living organisms. U.S. law currently offers 12 years of exclusivity, while Canada gives eight years and Mexico just five.

But Democrats pushed back, saying the provision would lock in high drug prices for patients, granting monopolies to pharmaceutical companies.

“California’s life science industry, a world leader in biomedical innovation, would be among the first to suffer,” said Joe Panetta, president and CEO of Biocom, a San Diego-based trade group. “Small and emerging companies … rely on intellectual property protections to compete in global markets.”

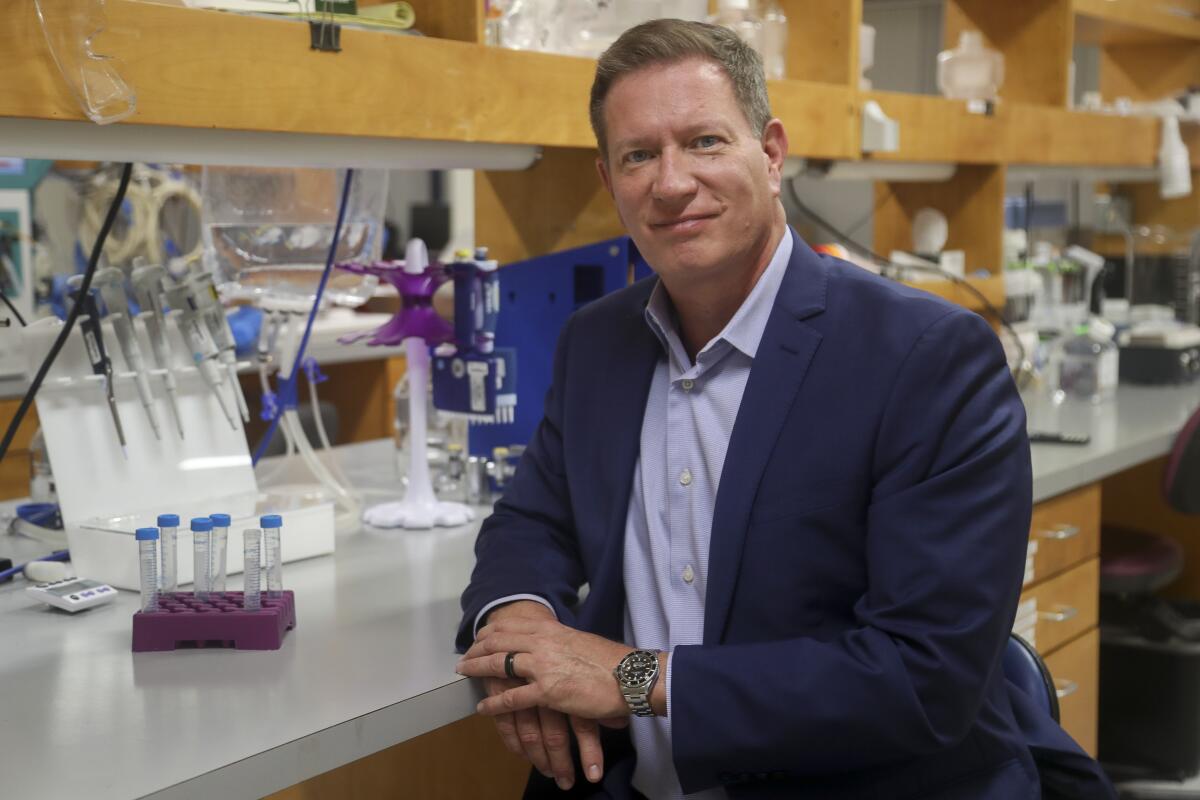

Histogen, a San Diego company with 25 employees, has raised $39 million from investors and $20 million in licensing fees as it seeks to develop a hair-growth drug. “For a company like ours to spend millions of dollars on clinical trials, there has to be some assurance we can recoup those costs,” said Richard Pasco, Histogen’s chairman and chief executive.

“Mexico and Canada are not driving the innovation to bring these new technologies forward,” Pasco said. “They are waiting for us to do it.”

By failing to align protections against generic copycats across the region, he said, biologic companies are less likely to market their products in Canada or Mexico. “Why would we file for approval in one of those countries if they can copy our products and ship them back across the border at a cheaper price?” he asked.

Pasco acknowledged that with public criticism of high pharmaceutical prices, “the optics are not ideal for drug companies.” But he asserted, “Prices are largely dictated not by drug companies but by benefit managers and the insurance companies they work for.”

FARMING

The dairy industry lauded USMCA’s gradual opening of dairy sales to Canada, which has strict production controls, including import quotas protected by whopping three-digit tariffs. In the short term, Wisconsin and New York could benefit, as their dairies have been shut out of exporting a processed milk component used for cheese. California dairy farmers, however, are more focused on the Mexican market, the biggest buyer of U.S. dairy exports.

Column: California’s dairy farmers were struggling to regain profitability. Then came the trade wars

“The overall feeling is that we hit ‘peak cow’ five or six years ago.”

The agreement also includes a limited opening to Canada’s market for American eggs and poultry.

The California wine industry won a commitment to settle provincial-level squabbles over shelving and marketing of U.S. wine. Canada is the top single-country destination for California wines, buying nearly $450 million worth in 2018, according to the Wine Institute, an industry advocacy group. (The European Union’s 28 members are the top export market.)

California vintners have been in a long-term spat with British Columbia over how it segregates U.S. imports and favors domestic labels on store shelves, making it difficult to find California wines.

Don Lee in Washington and Russ Mitchell in San Francisco contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.