Column: Buttigieg is wrong — free college should be free for all, including children of the rich

- Share via

Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg has taken aim at one of the most progressive planks in the platforms of his rivals Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren — eliminating tuition charges at public universities.

In an ad running in Iowa, the first primary battleground state, Buttigieg attacks their proposals for making college “free even for the kids of millionaires.”

Buttigieg’s comment was called out by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), a Sanders supporter, who labeled it “a GOP talking point used to dismantle public systems.”

I don’t think taxpayers should be paying to send Donald Trump’s kids to college.

— Hillary Clinton, 2016

Here’s the bottom line on this campaign dustup: Buttigieg is wrong, and AOC is right.

The argument that public programs designed to be universal are somehow flawed because they benefit all echelons of society, rich and poor alike, indeed is a common Republican talking point. It’s so superficially logical, in fact, that it’s not uncommon to hear it leaching into Democratic Party policy debates.

Hillary Clinton, for instance, used it to great effect against Sanders’ free college plan during a Democratic debate in 2016: “I don’t think taxpayers should be paying to send Donald Trump’s kids to college.” At the time I fell into this same trap in a critique of Sanders’ proposal.

Yet as Ocasio-Cortez observed, the argument has a nasty subtext and ugly consequences. Social programs that serve limited economic groups, especially the middle-class and poor, are always more vulnerable to political attack than those that serve everyone. Since diminishing the ability of government to assist those in need is Republican orthodoxy, supporters of social programs should be very wary of applying this applause line to programs they value.

Let’s bring back the idea of a free UC education

What’s more, limiting social programs by economic status leads to a particularly noxious and demeaning procedure known as means-testing, which can allow officials to pry into the most private aspects of applicants’ lives. The process tends to discourage applications, thus serving the goal of making the programs less useful for beneficiaries.

For examples of how this system works, consider three government assistance programs: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF, which is commonly described as welfare; food stamps; and Medicaid. What all three have in common is that they’re income- or asset-based and means-tested — applicants generally have to show that their financial resources fall below a certain floor.

What they also have in common is that they’re the targets of relentless conservative assaults. TANF recipients are subjected to numerous restrictions and rules beyond simply showing their financial need. Congressional Republicans have tried for years to cut food stamp benefits, which are by no means lavish, and to dictate which foodstuffs they can be used for.

The Trump administration and Republicans in Congress have consistently called for “block-granting” Medicaid, an arrangement almost certain to diminish Medicaid’s ability to serve the healthcare needs of its beneficiaries, their communities and their states.

Not uncommonly, these attacks are typically infused with the utmost hypocrisy. My favorite example comes from a 2013 effort in the then-GOP-controlled House to cut $20 billion from food stamps over 10 years, which would throw some 2 million recipients off the rolls.

Rep. Doug LaMalfa (R-Richvale) argued that the food stamp program was a sign of “oppressive” government and that helping the poor is better left to individuals and churches because then “it comes from the heart, not from a badge or from a mandate.”

As it happens, LaMalfa and his family had been the recipients of $5.1 million in government crop subsidies over the previous 17 years.

Among universal programs, Social Security is often the target of proposals for means-testing. Typically the argument refers to billionaires like Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, who are eligible for Social Security checks although Lord knows they don’t need the money.

The pioneer of this argument was hedge fund billionaire Pete Peterson, who waged a years-long campaign to cut Social Security benefits on the grounds that America, then as now the richest land on Earth, couldn’t afford them. But it gains its force from the constant overblown drum-beating about Social Security’s fiscal “crisis”; the idea is that cutting off benefits to the rich will help balance Social Security’s books.

The reality is that only a minuscule portion of Social Security benefits goes to the wealthy. As Dean Baker and Hye Jin Rho of the Center for Economic and Policy Research showed in 2011, only 0.6% of all benefits go to recipients with non-Social Security income of $200,000 or more, while 90% go to retirees with less than $29,000 in outside income. For means-testing to have a meaningful impact on Social Security’s finances, benefits would have to be cut for households earning as little as $40,000.

Social Security retains its broad public support largely because it is universal: If you’ve touched even a minimal amount of covered earnings over a career, contributing payroll tax all along the way, you’re entitled to your benefits, end of story.

The same goes for other universal programs and services deemed to be public goods, such as K-12 education and public libraries. We understand that they’re investments in the future that yield more in benefits than they cost. No one argues for banning the kids of millionaires from public schools or public libraries, even though they can afford to attend private schools or buy their own books (and do).

When it comes to higher education, this basic truth seems to have fallen to the wayside. The principle underlying critiques of the Sanders and Warren proposals such as Buttigieg’s is that universal public college will allow rich kids to shoulder middle-class and poor students out of the way.

In its most absurd version, conservative commentator Stuart Butler attacked a plan for free community college proposed by Barack Obama in his 2015 State of the Union address by suggesting that it would attract rich kids to these two-year colleges, despite abundant evidence that the wealthier the family, the more likely its offspring will opt for four-year universities, generally private.

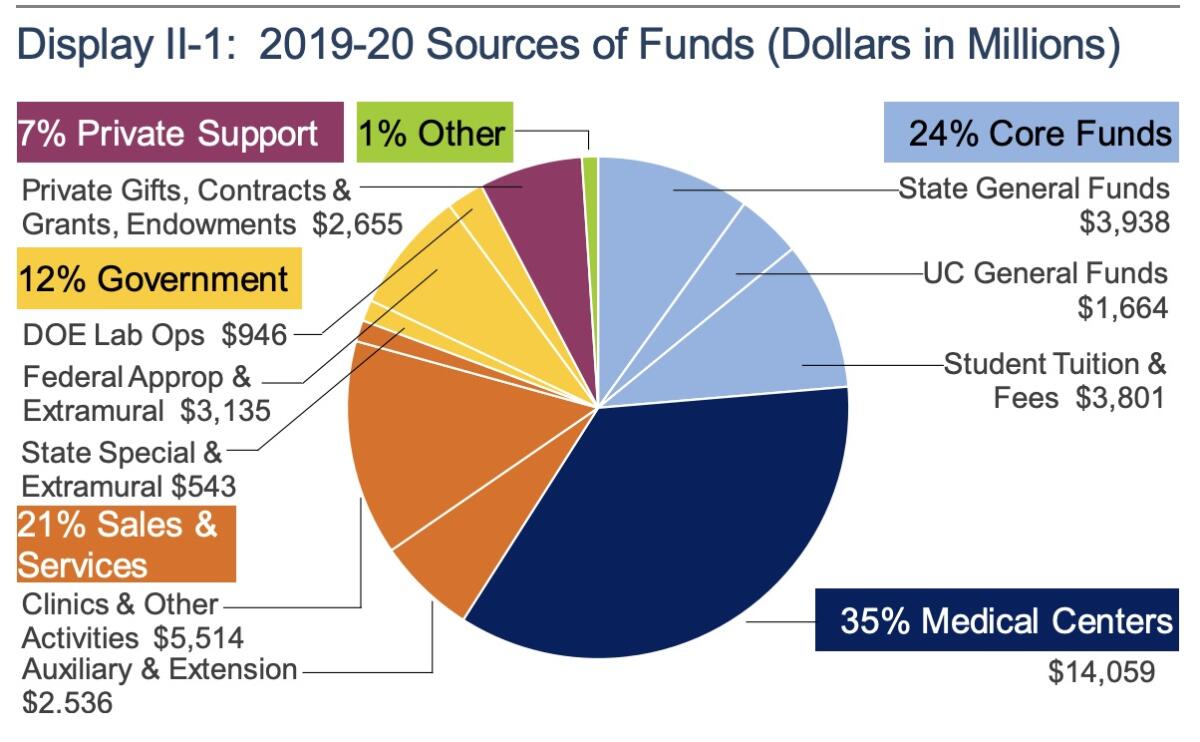

As Warren and Sanders understand, the cost of public higher education has become a major burden on middle-class and low-income families. In part that’s because state governments have bailed out as funding sources. In California, for example, the state general fund now contributes less than 10% of the University of California budget.

The state government’s cheeseparing forces UC to accept more out-of-state students, who pay $43,800 a year compared to state residents’ $14,000. The harvest can be seen in acceptance statistics. Among students admitted as freshmen this year, only about 66% were Californians. The rate was about the same at Berkeley but lower at the system’s other premier campuses such as UCLA (about 61%) and San Diego (57%).

That amounts to an abandonment of what was long regarded as a key to California’s economic growth — free tuition at UC and California State University. As we’ve reported in the past, California educated a host of great Americans effectively for free. Among UC’s graduates in the era before tuition were Earl Warren, a governor and chief justice, diplomat Ralph Bunche, Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley, physicist Glenn Seaborg, and writer Maxine Hong Kingston. (To be fair, UC started charging students a nontuition “incidental” fee of $25 in 1921, the equivalent of about $340 today.)

The truth is, of course, that some seemingly universal programs have features that might be interpreted as subtle forms of means-testing. Social Security benefits are lower as a percentage of lifetime earnings for high-income recipients than for those at the lower end of the earnings scale. A higher proportion of benefits paid to the wealthy are subject to income tax, too. Medicare charges higher premiums for retirees with higher incomes.

That points to the right way to keep even universal programs “progressive,” in the sense of delivering proportionately greater benefits to those who need them more: Raise taxes on the wealthy so they pay more to support universal programs.

In recent years, America has gone in the opposite direction. We’ve cut taxes on the very rich, then pointed to the higher deficits resulting from the tax cuts as an argument for cutting social programs. Keep your eye on this sleight of hand whenever Republicans start moaning about the cost of “entitlements.”

In light of all this, the problem with Buttigieg’s complaints about free public higher education should be clear. For any such program to retain public support it needs to be truly all-encompassing, not an assistance program for just some of us. He should embrace universality, not decry it as a giveaway.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.