Column: Two rival experts agree — 401(k) plans haven’t helped you save enough for retirement

- Share via

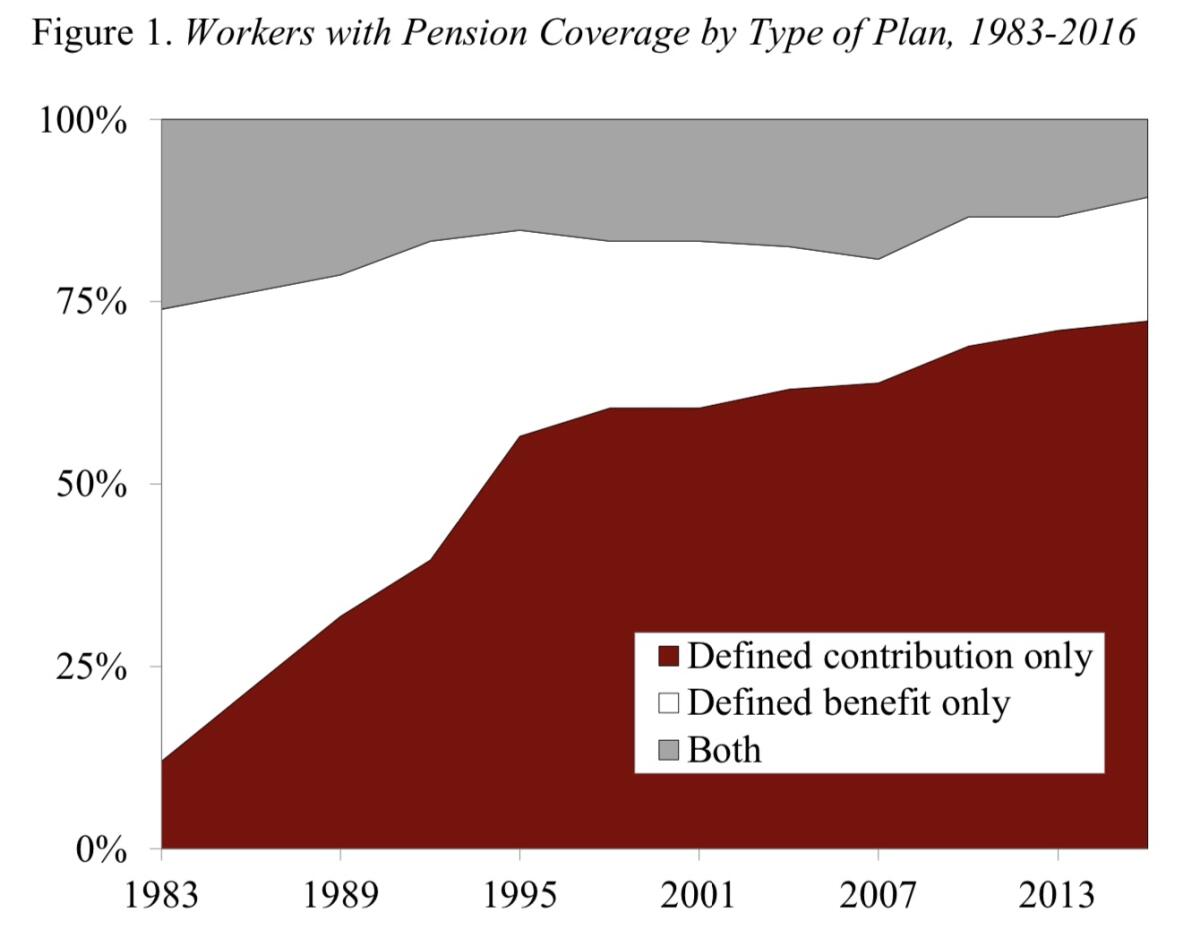

Retirement experts have debated for years over the consequences of America’s shift from traditional pensions to 401(k)s and other so-called defined contribution plans.

Among the issues at hand: Do the new-style plans leave too many workers behind? Do they saddle employees with too much risk? Do they increase economic inequality?

It’s fascinating, then, to see that two experts who commonly come at these questions from opposite sides of the political divide have collaborated on an important new analysis of how 401(k) plans have been working — and reached agreement that the plans haven’t been working well enough to help workers save for retirement.

The lack of universal coverage means that...401(k)/IRA plans will continue to fall below their potential.

— Biggs, Munnell and Chen

They find that for various reasons, balances in defined contribution plans at retirement age are falling significantly short of what they could and should be. Some of the blame falls on the system itself, some on bad choices made by workers. More on that in a moment.

The study, published by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, is titled, “Why are 401(k)/IRA Balances Substantially Below Potential?” Its authors are Andrew G. Biggs of the pro-business American Enterprise Institute and Alicia H. Munnell, the center’s director. They were assisted by the center’s Anqi Chen.

One doesn’t normally find Munnell and Biggs on the same page. Munnell, who was a Treasury official and economic advisor to the White House under President Clinton, has been sounding the alarm about the coming retirement crisis, in which Americans face their longer post-career lifespans without adequate financial resources.

Biggs’ theme has been that the retirement crisis is “phony,” in that retiring Americans have a lot more to spend than is commonly acknowledged. He has also been an advocate of Social Security privatization, which Munnell opposed, and a critic of plans to increase and expand the program’s benefits.

It might have been instructive to listen in as Munnell and Biggs developed their paper. As a close follower of the work of both, I almost imagine I can identify some of each author’s particular contributions. That would only be a distraction from the very instructive conclusions they arrived at together, so let it go.

Some background first. In traditional, or “defined benefit,” pensions, retirement payouts are based on a worker’s wage history and longevity with a given employer. These plans are typically back-ended, meaning their value builds exponentially faster toward the end of the worker’s career, rewarding those who stick with the employer the longest. They’re generally not portable as workers switch employers, so inveterate job-hoppers can end up with very little at retirement.

Employers bear the economic and market risk of these plans, which is one reason they’ve been disappearing fast, especially in the private sector.

Defined contribution plans such as 401(k) plans require employees to invest a portion of their wage income, sometimes partially matched by the employer, most often in stocks, bonds or mutual funds; the contributions are tax-deferred: The worker doesn’t pay tax on the contributions when they’re made or on annual gains in the account, but withdrawals in retirement are taxed as ordinary income.

Employees bear all the economic and market risk of these plans — in the aftermath of the 2000-02 and 2008 crashes, many discovered that their plans’ balances had shrunk by 30% to 40%, leading to the wry joke that their 401(k)s had become 201(k)s.

One of the mysteries of personal finance has been the disconnect between the income inequality afflicting the working public and the claims by fiscal conservatives that most people’s retirement lifestyles will be perfectly comfortable.

But the plans are portable — workers can take their balances with them when they change jobs, frequently by rolling them into individual retirement accounts. Since the vast majority of IRAs were opened to accommodate 401(k) balances, Munnell and Biggs examine 401(k) plans and IRAs together.

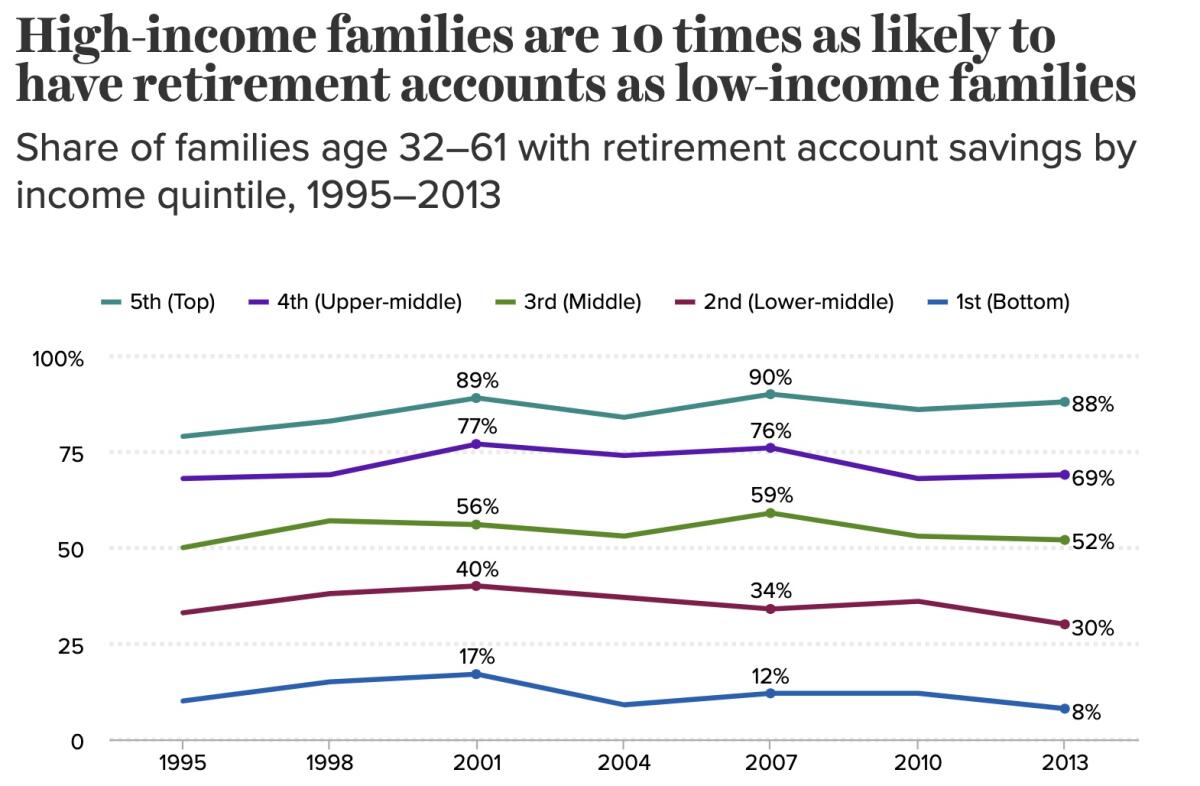

One other observation: Employee participation in 401(k)-type plans is much more unequal than in traditional plans. The union-oriented Economic Policy Institute reported in 2016 that 68% of households in the top 20% of the income ladder had 401(k) plans, but only 4% of those in the bottom 20% of income. By contrast, 27% of the top fifth and 6% of the bottom fifth had defined benefit pensions. Munnell and Biggs gloss over this imbalance, as we’ll see.

The authors’ main goal is to figure out why balances in 401(k)s and IRAs fall so far short of their potential. They define this potential as what workers earning median wages should expect to accumulate if they invest consistently from age 25 through age 60. They calculate that figure as $364,000. The typical 60-year-old with a 401(k), however, has only $92,000.

Munnell and Biggs make the same calculation for workers who don’t start saving until age 30, excluding those with defined benefit pensions and therefore less incentive to save. For them, the potential balance should reach $270,000 at age 60, but the average holding for this group is only $90,000.

What accounts for the shortfall?

The authors place the largest share of blame on the defined contribution system’s “immaturity.” As they observe, 401(k) plans became legal only in 1980, and began to surge only toward the end of that decade. As a result, “many of today’s 60-year-olds did not participate in a 401(k) plan when they were young workers.” That suggests that future workers, who will have invested for retirement all throughout their careers, should reach retirement age with healthier balances.

Moreover, not all employers offer 401(k) plans to their workforces. That’s especially true of medium-size and small employers. Some companies offer them only to full-timers. And even among eligible workers, not all choose to participate. This can be the result of inertia — some workers never get around to signing up.

A 2006 change in federal law encouraged employers to automatically enroll new employees in these plans unless the employee opted out. Indeed, participation in auto-enrollment plans has been estimated to be one-third higher than in opt-in plans. Inertia can work both ways.

Munnell and Biggs estimate that the immaturity of the system and the lack of universal coverage together account for two-thirds of the shortfall from potential savings. Then come the fees charged by the investment firms managing the employee accounts. These have come down considerably from the mid-1990s.

Elizabeth Warren’s plan, like the others, addresses many of the shortcomings long identified by the program’s advocates, columnist Michael Hitzik writes.

Typical fees on stock funds have fallen to 0.59% of balances from 1.04%, and on bond funds to 0.48% from 0.84%, largely because the government started requiring fee disclosure in 2012. But they’re arguably still too high, given how easy it is for an investment firm to manage accounts that don’t generally involve a lot of transactions. Even modest fees can considerably erode an investment balance over time. Munnell and Biggs estimate that fees account for about 4% of the shortfall.

That leaves what they call “leakage.” These are early withdrawals from retirement accounts. They include cashing out a plan when one changes jobs, and not rolling over the balance to a new plan; making “hardship” withdrawals for purposes such as medical expenses, college tuition, or to buy a home or avoid eviction; and taking out a loan from a plan and failing to repay it. Those withdrawals all are subject to a 10% tax penalty, but that doesn’t seem to be onerous enough to discourage more leakage, especially for workers with small balances and larger needs.

Estimates of the annual leakage from 401(k) plans range as high as 2.9%, and the cumulative loss from these early withdrawals accounts for more than 8% of the shortfall, by the authors’ reckoning.

Munnell and Biggs suggest that tightening early withdrawal rules could reduce leakages. They don’t specify what should be done, although raising the withdrawal penalty and eliminating some “hardship” options would seem to be obvious possibilities.

Nor do they make recommendations on how to achieve universal participation, though they acknowledge that “the lack of universal coverage means that — even once the system matures — 401(k)/IRA plans will continue to fall below their potential.”

There are limits to how far Congress would go to mandate that employers offer retirement plans, but there’s another factor the authors don’t really confront. One reason that some workers don’t participate in defined contribution plans even when they’re eligible is that they don’t have the money.

A household living paycheck to paycheck may simply find it impossible to set aside even a few percentage points of wages to fund a far-off retirement. In other words, the insufficiency of retirement savings in many working households is another reflection of income inequality. People are working harder for less return because wage earners don’t share equitably in an economy where a disproportionate share of national income goes to the wealthiest households. As long as that problem goes unaddressed, retirement plans won’t be the only aspects of working America failing to reach their potential.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.