Column: Facebook’s bogus video claims just cost it $40 million, but they caused much more damage

- Share via

Facebook managed to extricate itself from one of its many scandals last week on the cheap, paying a mere $40 million in cash to settle allegations that it defrauded advertisers by feeding them fake estimates of the viewership of video ads in 2016 and 2017.

In the Facebook universe, this is the chumpiest of chump change. The company collected more than $22 billion in profit last year, on revenue of $55.8 billion, so it could cover the $40-million bill out of about 16 hours of profits.

But the damage its vaunted “pivot to video” wreaked in the media and advertising industries in 2016 and 2017 was much greater, and is still being felt. Based on what Facebook described as a commitment to become an “all video” platform, media companies dependent on its audience of roughly 2 billion leaped whole-hog into video production.

If we look already, we’re seeing a year-on-year decline on text. If I was having a bet, I would say: video, video, video.

— Facebook’s Nicola Mendelsohn gets it wrong, 2016

News organizations laid off text-oriented reporters and editors by the score, making room for videographers and producers.

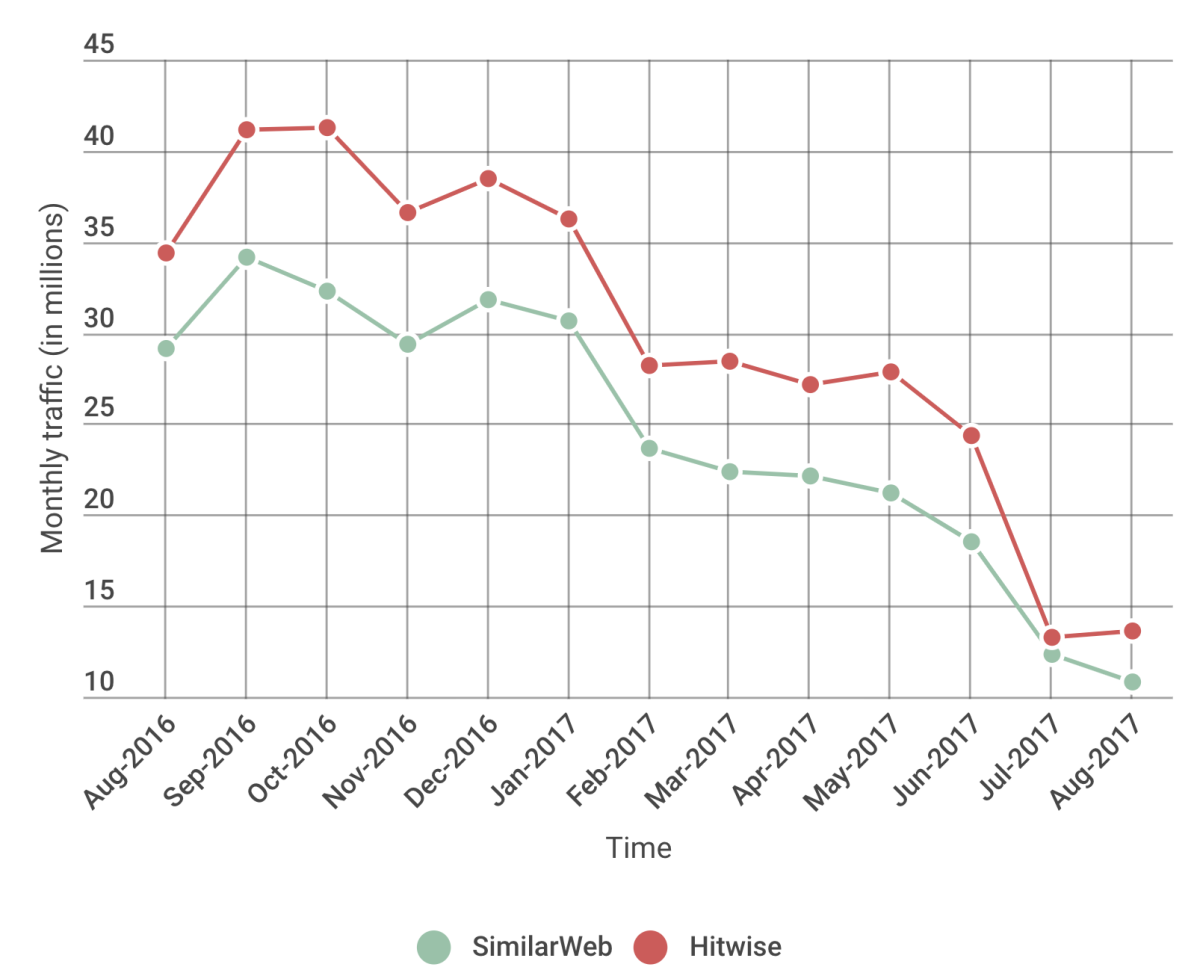

Many of those sites quickly discovered that, Facebook’s claims notwithstanding, they were feeding their own audiences a product they didn’t want. Website traffic cratered. Within about a year, several online publishers that had pivoted to video were retrenching again -- in part because Facebook had decided to downplay videos from outside sites on its own pages.

Among the sites that had shifted to video, only to find that the strategy was less than successful, were Mic and Vox, the latter of which laid off 50 employees, mostly in its social video team, in 2018. Vox Media CEO Jim Bankoff explained then in a memo to staff that the company had concluded that its social video initiatives “won’t be viable audience or revenue growth drivers for us relative to other investments we are making.”

Facebook’s on-again-off-again flirtation with video isn’t the only misdeed the social media company has been blamed for. The biggest involves the breach of Facebook users’ privacy through the data mining firm Cambridge Analytica, a Facebook customer; that resulted in a record $5-billion fine imposed in July by the Federal Trade Commission.

The FTC absolves Zuckerberg and Sandberg of responsibility for Facebook’s privacy violations.

But the video advertising affair is one of the more costly and long-running disputes involving the company. According to a lawsuit filed by a group of advertisers in Oakland federal court in 2016, the issue dates back to 2014 when the company began providing its advertisers with statistics showing how much time the average user spent viewing their video ads. These were crucial numbers, because they helped advertisers judge the effectiveness of their spending on the platform.

The pitching of video to advertising clients dovetailed perfectly with Facebook’s broader strategy. In June 2016, Facebook executive Nicola Mendelsohn declared that within five years, the company’s platform would probably be “all video” -- rendering the written word essentially dead.

“If we look already, we’re seeing a year-on-year decline on text,” Mendelsohn said at a Fortune Magazine conference in London. “If I was having a bet, I would say: video, video, video.” That’s because “the best way to tell stories in this world, where so much information is coming at us, actually is video. It conveys so much more information in a much quicker period. So actually the trend helps us to digest much more information.”

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg underscored the company’s strategy. “We’re entering this new golden age of video,” he told BuzzFeed News in 2016. “I wouldn’t be surprised if you fast-forward five years and most of the content that people see on Facebook and are sharing on a day-to-day basis is video.”

These assertions about the information content and accessibility of video versus text, and about the platform’s future, were both exactly wrong. But the spiel filled a vacuum in the information sectors about what worked online.

As the advertisers learned in 2016, however, Facebook’s numbers were bogus. The company disregarded views that lasted less than three seconds — that is, all the times that a user simply scrolled past a video scarcely registering it at all. Thus the resulting formula vastly overstated average viewing time, skewing the advertisers’ judgments. Facebook says in its defense that it corrected the error promptly after it was discovered and made a public announcement to that effect in September 2016. Facebook told some advertisers that the error inflated the viewing time measurements by 60% to 80%.

The plaintiffs in the federal lawsuit say Facebook is still fudging. They allege that the company’s engineers knew of the errors for more than a year before the public announcement, and that average viewership measurements had actually been “inflated by some 150 to 900%.” They assert, moreover, that Facebook showed “reckless indifference” to the accuracy of its metrics, understaffing the engineering team assigned to fix the errors and pursuing a “no PR” strategy to conceal that it “screwed up the math.”

Facebook executive Nicola Mendelsohn shook up the online-o-sphere earlier this week with one of those offhand declarations that sound superficially profound for a moment or two but are vacuous at their core.

The plaintiffs, who were seeking to make their lawsuit a class action, say they could have recovered damages of as much as $200 million at trial, but chose to settle instead for $40 million because Facebook’s ferocious defense — it tried repeatedly to get the case thrown out of court — made the outcome too uncertain. Facebook has essentially argued that the plaintiffs weren’t damaged, because the length of time viewers spent with the ads had nothing to do with what advertisers were billed.

Of the $40 million, the plantiffs lawyers stand to collect about $12 million. All those sites that made a bad bet on video or the employees who lost their jobs in the video craze — they’ll get nothing.

Facebook doesn’t deserve all the blame for the carnage. The truth is that there was never a great deal of evidence to suggest that online users liked video much, especially when their goal was to obtain information. The impression that video was the coming thing was fueled by occasional clips that went viral. But these often were undernourishing curiosities, such as BuzzFeed’s famous 2016 exploding watermelon stunt (currently notched at 11 million views on Facebook).

Nor is there much logic behind the argument that video is the best way to communicate with an audience pressed for time and faced with myriad claims on its attention. As I pointed out when Mendelsohn first disclosed the all-video-all-the time strategy for Facebook, video is hopelessly inferior to text in conveying facts, figures, data and other hard information.

Video is a linear medium: You have to unspool it frame by frame to glean what it’s saying. Text can be absorbed in blocks; the eye searches for keywords or names or other pointers such as quotation marks. Also, text is generally searchable online, a function that still works spottily at best for video.

A typical episode of “Meet the Press” takes an hour to play out (that’s about 47 minutes of programming other than commercials), but its transcript, comprising about 10,000 words, can be scanned in a few short minutes. If you want to find the moment in the full episode of last Sunday’s episode when Chuck Todd upbraided Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Ohio) for trying “to make Donald Trump feel better” by filibustering on the air, you’d have to spool through nine minutes of video, but could search and find it in the blink of an eye in the transcript.

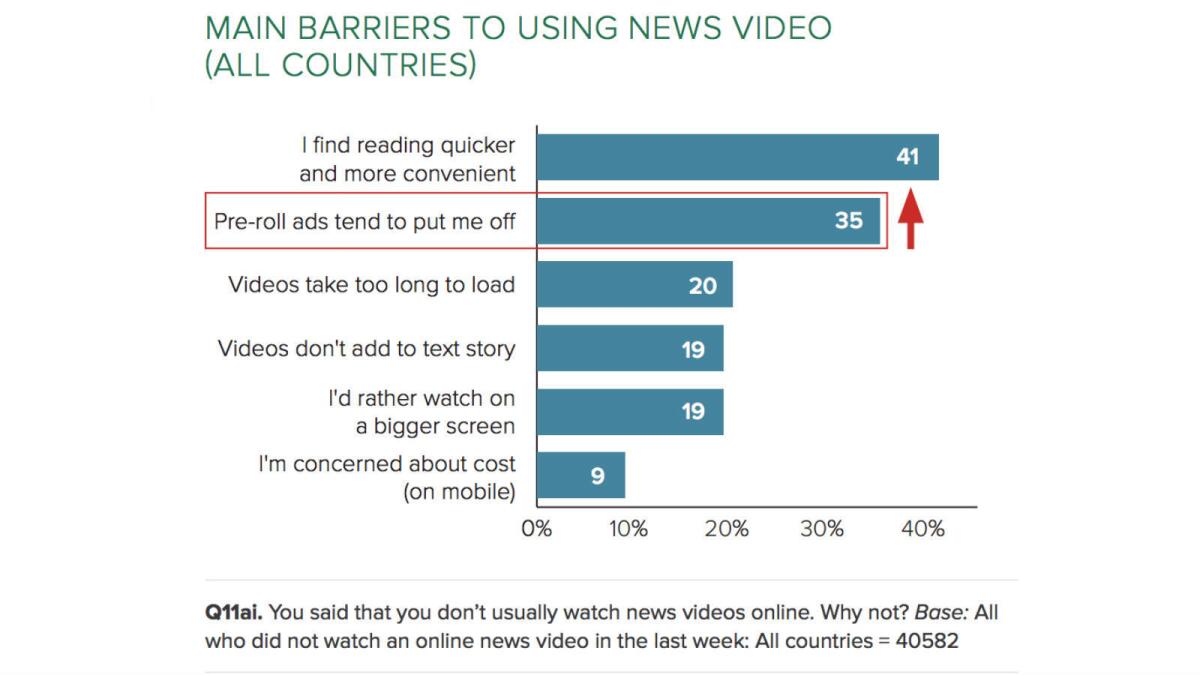

The ways in which video clips are pushed to users also work against their convenience and acceptance. Typically they’re preceded by an ad lasting 15, 30, or even 60 seconds. (Facebook experimented with moving ads to mid-clip, but since users seemed to take the ads as a signal to abandon the clip rather than wait for it to resume, the test was quickly abandoned.) Users sometimes aren’t even aware they’re about to view a clip until the soundtrack starts blasting unbidden from their phones or laptops.

Video doesn’t lend itself to multitasking. Watch a clip while strolling on the street, you may walk into a lightpost; watch while driving, you’ll get a ticket or end up in a ditch. That may be why podcasts have proven so much more popular — they can be listened to while performing chores around the house or even on a commute.

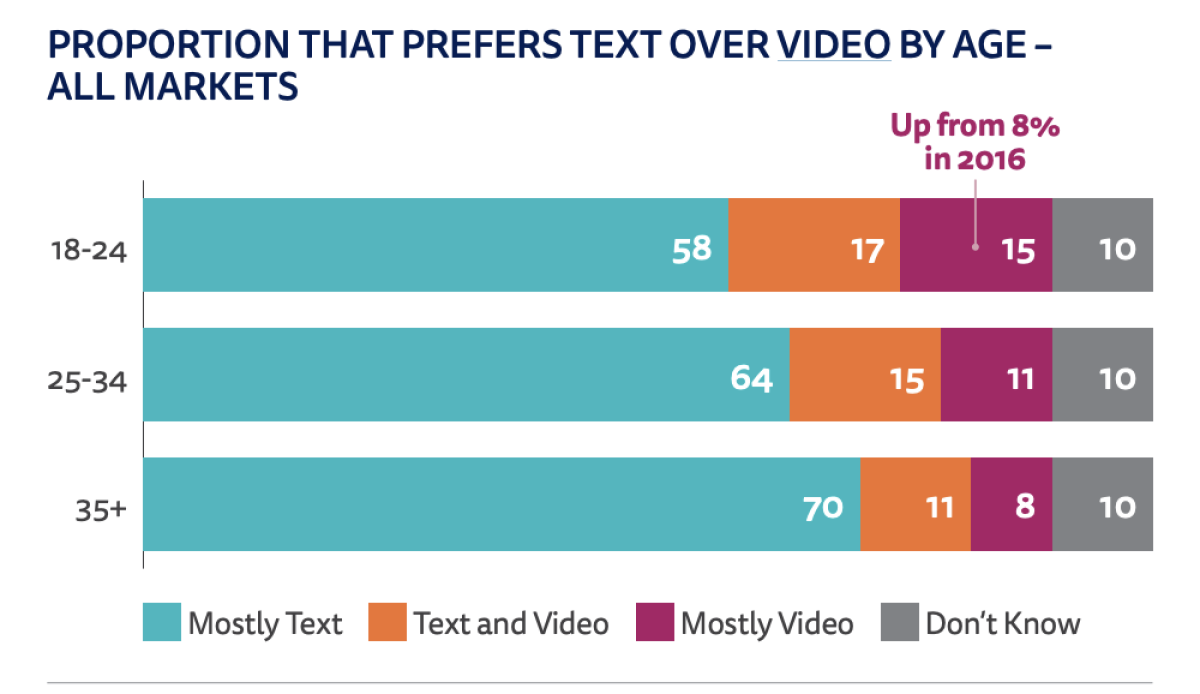

User resistance to getting news via video has been well documented. A majority of users in all age groups prefers text to video, according to a survey published earlier this year by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University. About 70% of those 35 and older preferred text over video. In the 18-24 age group, a solid majority of 58% preferred text, though 15% preferred “mostly video” — the largest proportion of any age group.

The top reasons for this preference, according to a 2016 report from the same institute, were that users found reading “quicker and more convenient” than watching a video, and were put off by “pre-roll ads.”

None of this is to say that there’s no place for video on digital platforms.

Bite-sized videos traded among friends or promoting products are the stock and trade of Snap Inc. and Facebook’s Instagram product. Video is the ideal medium for conveying the immediacy of a dynamic event, whether it’s a rocket launch in Florida or a street demonstration in Hong Kong. A video interview with a person at the center of a news event can communicate emotion in a way that only the most gifted writer can communicate in print. Long-form documentaries that have been showing up on Netflix and YouTube, among other platforms, are worthy formats for story-telling — but they’re not well-suited for viewing via an iPhone on the fly.

Video may be better than text for entertainment and marketing. That’s because their goal is to distract, not communicate — and color, movement, noise and light can all be exploited to distract.

But the role of video in communicating hard information is still uncertain. Younger users are gravitating more toward video, but the transition is happening slower than many people expected even a few years ago. Online, text is still king. The written word can meld itself to people’s shrinking attention spans in ways video hasn’t. Facebook may have known this from the start. Otherwise, the advertisers’ lawsuit asks, why would it fudge the numbers?

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.