Column: Can labor unions lift themselves off the floor? A new book asks the question

- Share via

Whether organized labor in the United States is sounding a terminal death rattle or showing signs of a resurgence depends on one’s perspective.

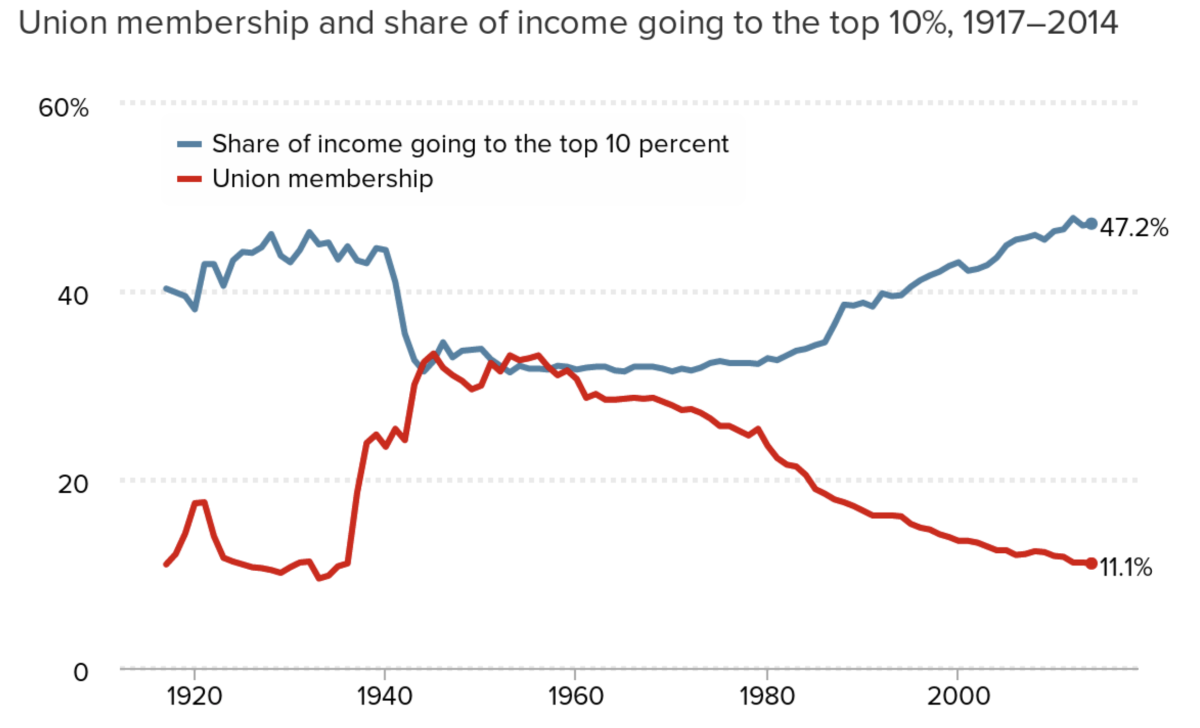

On the one hand, union membership continues to suffer a long-term decline, especially in the private sector — it’s down to less than 11% overall from its peak of nearly 35% in the late 1950s.

On the other, organized labor has notched some notable victories in recent years, including the fight for $15, which prompted California, Massachusetts and cities such as Los Angeles and Seattle to move their minimum wage to or at least toward $15 an hour.

In no other industrial nation do employers fight so hard to defeat, indeed quash, labor unions.

— Steven Greenhouse

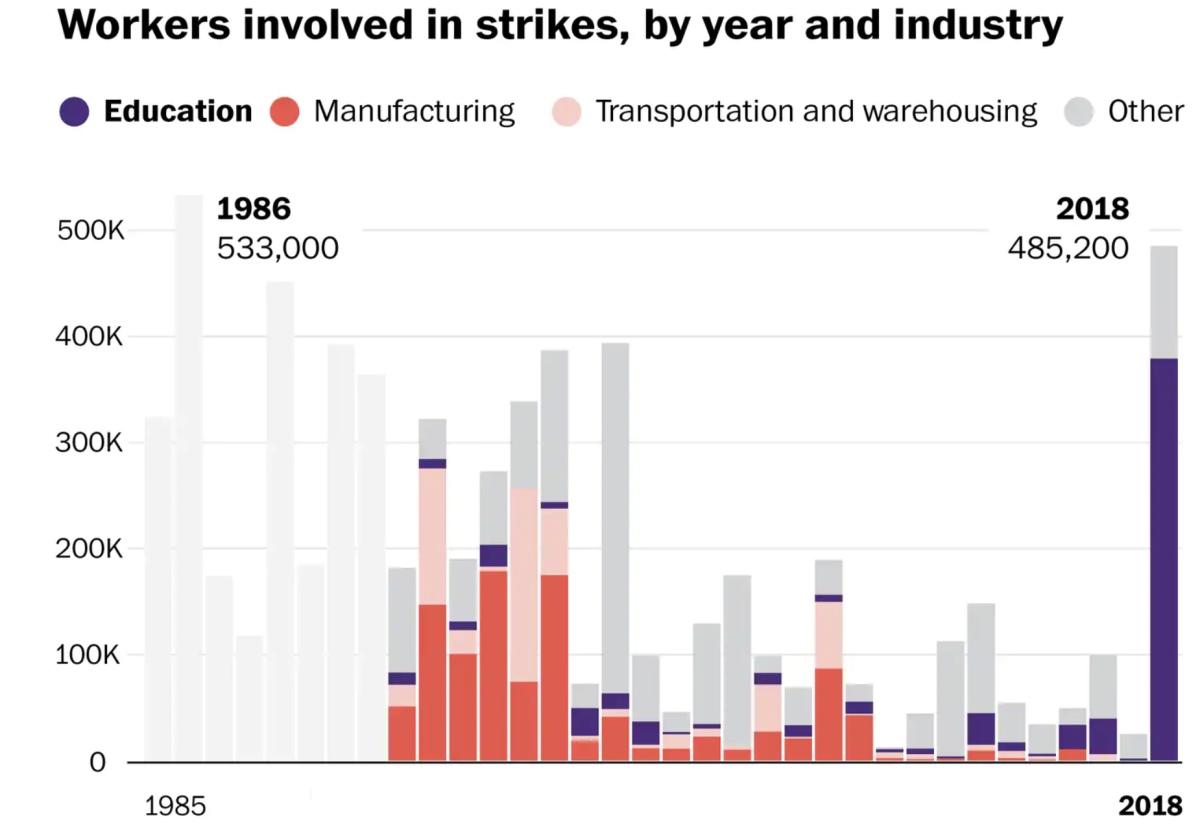

Teacher strikes in 2018 brought higher wages and improved working conditions for teachers in such locations as West Virginia, Oklahoma and North Carolina — long considered unpromising grounds for labor activism.

On the whole, however, things are not looking up. That’s the theme of Steven Greenhouse’s new book “Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present, and Future of American Labor,” which is officially published Tuesday.

UPDATE, July 12: In its latest report on wages, released Thursday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics said that earnings for all employees were unchanged in June from June 2017.

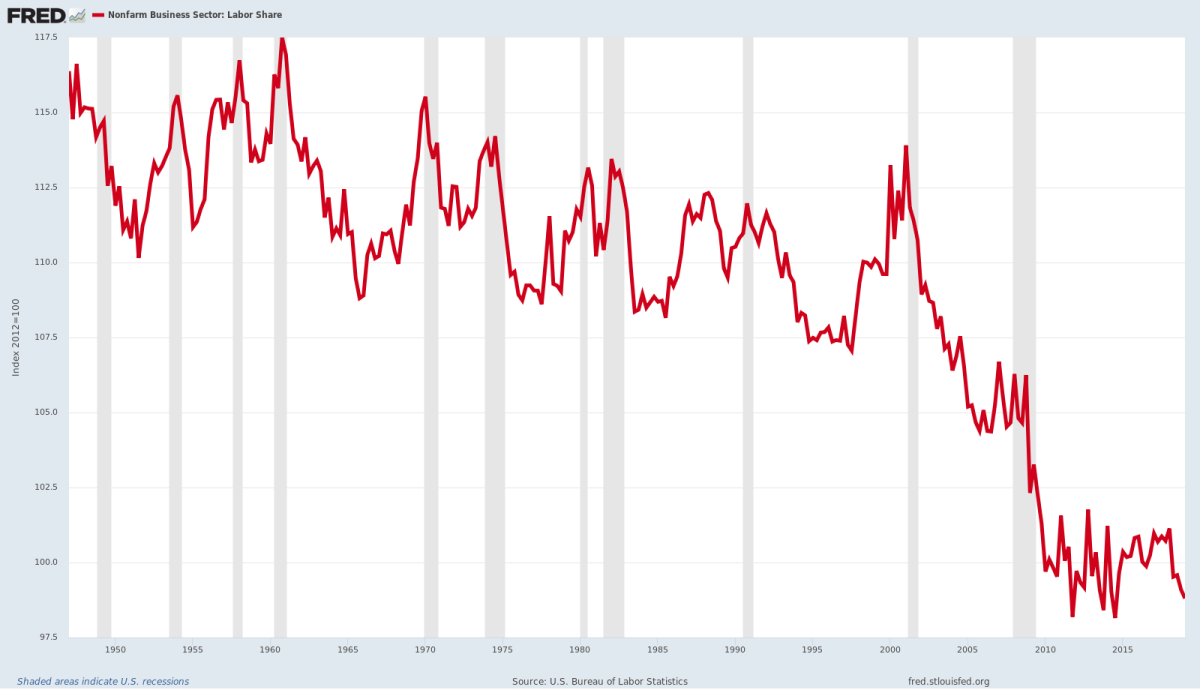

“One of the reasons I wrote the book is to sound the alarm that there’s been a real decline of worker power overall,” Greenhouse, who spent some two decades covering labor for the New York Times, told me recently. “Things have tilted very much in favor of corporations and the wealthy instead of workers.” Congress enacted a huge tax cut for the rich in 2017, but hasn’t budged on moving the federal minimum wage above $7.25.

“We’re seeing Donald Trump, who promised to help workers, taking away overtime protections and scrapping the fiduciary rule to protect workers’ 401(k)s. Young Americans don’t understand the importance of unions and worker power.”

Even if the 2000s are a period of less than unalloyed glory for organized labor, we may be entering another golden age of labor historiography. Greenhouse’s book comes on the heels of historian Erik Loomis’s book “A History of America in Ten Strikes,” which we wrote about in February. (They cover some of the same events, including the Flint sit-down strike against General Motors in the mid-1930s and the disastrous PATCO strike of air traffic controllers in 1981.)

They’re filling a gap left since the heydays of Melvyn Dubofsky in the 1990s and Irving Bernstein of UCLA, whose three volumes of U.S. labor history in the 20th century appeared from 1960 to 1985.

The Democratic Party lately has been striving to portray itself as a bulwark for the American worker, but it hasn’t done as much to place organized labor at the forefront of its platform.

Greenhouse’s book chronicles the rise of organized labor in the first half of the 20th Century and its dizzying fall in the following decades. The rise was fueled by a worker solidarity born of the atrocious working conditions of garment sweatshops in New York, punctuated by lethal episodes such as the Triangle Shirtwaist Company fire of 1911, which took the lives of 146 workers, including 123 women. The New Deal brought concrete protection for collective bargaining through the National Labor Relations Act of 1935.

Wartime employers negotiated for labor peace in the name of efficient production of materiel, and the economic prosperity that followed the end of World War II gave employees and employers alike an incentive to build on mutual good will. Walter Reuther, a target of the infamous River Rouge assault by Ford Motor Co. thugs in 1937, had become head of the United Auto Workers’ General Motors department.

Reuther and GM boss Charlie Wilson reached a groundbreaking five-year contract in 1950 — the “Treaty of Detroit” — including then-unusual pension and health benefits. As Greenhouse observes, the contract became a building block of the postwar American middle class.

The dream eventually faded. Greenhouse, like Loomis, sees the PATCO strike as a dismal turning point for American labor. Since history is written by the victors, the public impression of the striking air traffic controllers is of grasping workers who flouted federal law forbidding government employees to walk off the job while demanding a contract far more generous than other employees could win.

There’s plenty of truth in the impression, but what is generally forgotten today is that the controllers worked under unbelievably stressful conditions and that the Federal Aviation Administration had reneged on promised improvements. Still, PATCO misplayed a bad hand. The union never took steps to win fellow aviation unions, much less the public, over to its side.

The all-important Air Line Pilots Association crossed PATCO’s picket lines, which shattered its hopes of bringing air traffic to a halt. The public was irked by the inconveniences of flight delays and cancellations in the first days of the strike, and treated President Ronald Reagan as a savior when he got air travel back up to speed in short order, using military air controllers, renegade PATCO members and supervisors.

BMW layoffs exemplify the evisceration of the middle class

Most destructively, PATCO misjudged Reagan, who needed to show firmness in the first major crisis of his fledgling administration. He threatened to fire every striker — and did so. “The union walked straight into the firing squad and Reagan was happy to oblige them,” Greenhouse says.

PATCO’s failure didn’t only damage itself. The sea change in management treatment of organized labor reverberates to this very day. “That really emboldened managements to get tough. They saw the president of the United States bust a union and thought, ‘Why can’t we do the same thing?’” The strike “really changed the mood and the methods that management used in dealing with their unions and their workers.”

The GOP attacks a union drive at VW — though the company’s in favor

Things have only gotten worse since then. “In no other industrial nation do employers fight so hard to defeat, indeed quash, labor unions,” Greenhouse says.

Even foreign employers that coexist peacefully with labor at home have been confounded by corporate and political hostility to unions in the U.S. Volkswagen discovered that in 2014, when it took a hands-off approach — in fact, even a positive approach — to an effort by the United Auto Workers to organize a VW plant in Chattanooga.

“Volkswagen considers its corporate culture of works councils a competitive advantage,” a VW executive said at the time. But Tennessee’s Republican establishment, in the form of Gov. Bill Haslam and Sen. Bob Corker, a former Chattanooga mayor, picked up the slack, even threatening the company with retribution if the unionization vote succeeded. It failed, narrowly, as did a second vote this past June.

The consequence of this four-decade trend is the loss of the worker’s voice in the workplace and American politics. Opinion polls show that an overwhelming majority of Americans favor a higher minimum wage, paid sick days and paid family leave, but they’re not happening at the federal level because organized labor’s voice is drowned out by the money and political clout of corporations.

The glimmers of hope come from union movements that attract popular backing and “achieve gains not just for themselves but for the public at large,” such as the teacher strikes. “Successful strikes beget, encourage and inspire other successful strikes,” Greenhouse says. “Contrast that with PATCO, where a disastrous strike discouraged other strikes. The teacher strikes signaled that unions are off their knees and off their backs and are fighting again.”

Another piece of the puzzle is politics. The Democratic Party neglected the ties with organized labor that had been forged in the New Deal, which Greenhouse argues contributed to the electoral disaster of 2016. In that election, he observes, Hillary Clinton lost three states — Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania — that had been traditional labor strongholds. “If unions hadn’t grown so weak and the Democratic Party had done more to keep unions from declining, maybe they would have won those three states.” Indeed, union membership in Wisconsin, once the fount of progressive political thought, declined from 15% in 2008 to 8.1% in 2018, bringing the rate from above the national average to below the national average in a single awful decade.

An increased awareness of the consequences of unions’ decline, such as income inequality, stagnant wages and deteriorating working conditions, seems to be energizing the Democratic candidates for president. But the road back to labor’s health will be a long one.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.