This architect of classic Hollywood gets his own star turn

- Share via

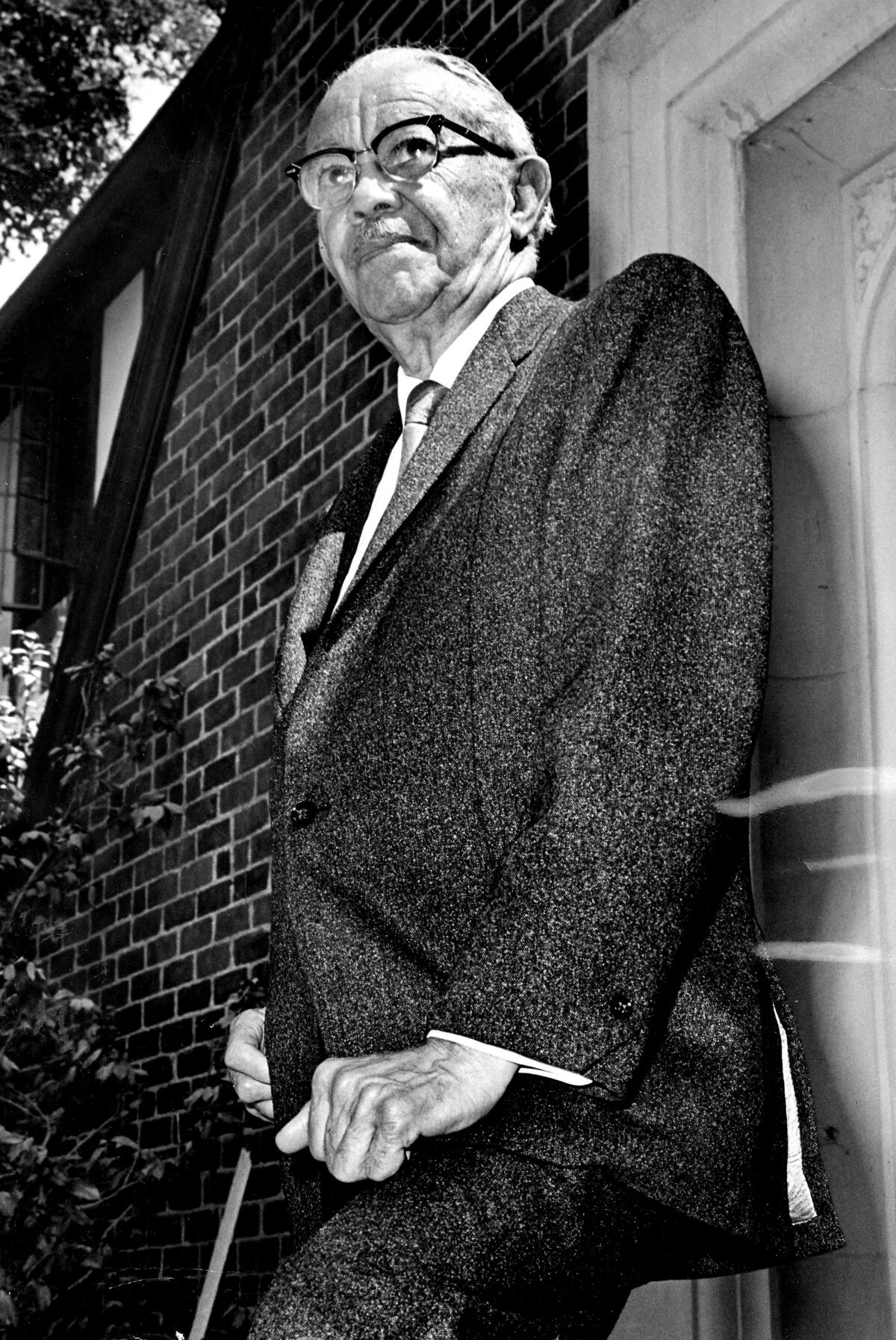

Some of Southern California’s most iconic buildings stand as silent monuments to a little-publicized pioneer.

Paul Revere Williams, the first African American member of the American Institute of Architects, not only designed homes for Hollywood legends from the 1930s through the 1960s but also helped fashion Los Angeles International Airport, the Angelus Funeral Home in South Los Angeles and a portion of the Beverly Hills Hotel.

The subject of three books by his granddaughter, Karen Hudson, Williams’ life and legacy are now the focus of an hourlong documentary with a Thursday premiere on PBS SoCal (KOCE-TV), and will show again Friday at 2 a.m. and Saturday at 4 p.m. Following the California debut, it will air on nearly 200 PBS stations across the country and be available to stream at PBSSoCal.org/hollywoodsarchitect.

In addition to giving Williams his close-up, filmmakers hope that “Hollywood’s Architect: The Paul R. Williams Story” will spark discussion of broader concerns.

“We want to do more than just a biopic,” said Royal Kennedy Rodgers, co-director and co-producer of the film, more than eight years in the making. “We talk about two of the biggest issues of today. One, the lack of diversity in the field of architecture, and also preservation is a big angle, because much of his work has been lost. There is a new focus in the African American community on preserving African American historic sites.”

Born in 1894 and orphaned at age 4, Williams overcame numerous obstacles to join a profession that remains largely white.

As a child, Williams described bumping into a “blank wall of discouragement,” according to the film, narrated by actor Courtney B. Vance.

That included a teacher who “very clearly told him, ‘You cannot be an architect,’” Hudson recounted in the film. ‘“Your people will not be able to afford you and white people will not hire you. Be a doctor or a lawyer, because your people always need those.’”

Williams gained his architect’s license in 1921 and got his big break a year later when he was tapped to design homes in the new community of Flintridge, in the San Gabriel Valley. During a career that spanned five decades, Williams designed more than 3,000 buildings across the globe.

His list of celebrity clients included Frank Sinatra, Cary Grant, Barbara Stanwyck, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. As a gift for actor and philanthropist Danny Thomas, a friend of his, he designed the original star-shaped St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis.

Yet during much of his career, Williams was blocked by racist laws and customs from living in many of the neighborhoods that contained his homes. And to forestall conflict with white clients, who might balk at sitting next to him, Williams learned how to sketch his designs upside down — a skill that became his trademark.

“The Paul Williams story is really one of inspiration and motivation and dedication,” said Kathy McCampbell Vance, co-director and co-producer (no relation to Courtney Vance).

“This man was facing incredible odds from his birth to the time he died,” she said. “Yet he rose to a level of elegance and eloquence that few people who have been given a silver spoon rise to. He had to have true grit in order to survive and navigate this world.”

Williams died in 1980 at age 85. Since the 1990s, interest in his accomplishments has been slowly growing.

At its 2017 convention, the American Institute of Architects gave a posthumous Gold Medal, its highest honor, to Williams, the first African American architect to win the award.

Between 1993 and 2012, Hudson published three books on her groundbreaking grandfather: “Paul R. Williams, Architect: A Legacy of Style” (Rizzoli, 1993), “Paul R. Williams, Classic Hollywood Style” (Rizzoli, 2012) and “The Will and the Way” (Rizzoli, 1994), a biography for grade-schoolers.

Kennedy Rodgers, a former PBS producer and correspondent, became interested in Williams’ story after hosting a book party for Hudson. She brought in McCampbell Vance and the two approached PBS.

“Paul Williams designed in so many different styles that I don’t think he was appreciated for being a great architect, because he didn’t have quote unquote, a particular style,” observed Michelle Merker, program development manager with KOCE-TV. “He really built whatever the client wanted, and that’s what made him so unique.”

Hudson and Kennedy Rodgers hope the documentary will introduce Williams to a new audience.

“While coffee-table books are significant records of an individual’s work, they are not always available to everyday people,” Hudson told The Times. “Any vehicle that brings his life and legacy alive through visual means, like a documentary, simply enhances the journey.”

In 2015, more than 90 years after Williams became the AIA’s first African American member, a study by the organization showed its black membership still was less than 2%.

“We’ve experienced architecture mostly [from] the perspectives of white males,” said Michael Ford, a designer with international architectural firm SmithGroup, who’s helping create a hip-hop museum in the Bronx. “We can see in the body of work of Paul Williams that there are other great design minds.”

Ford said he hopes Williams’ story, and others that will surface, become reference points that “move things forward on a quest to diversify the profession.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.