Totally Worth It, Week 5: Paying off debt

- Share via

The whole reason I got into budgeting was to make a dent in my debt.

Last week, we talked about how to cut expenses. But for most of us, there’s only so much wiggle room. You’ve streamlined your subscriptions and are making a conscious effort to pack your lunch. But if you have student loans, plus a car that isn’t paid off and a couple of credit cards carrying a balance, even low monthly minimum payments add up quick — and can take up a surprising portion of your income.

It used to be legal for credit card companies to make your monthly minimum payment so low that you would never get out of debt by paying only that amount each month. That changed under the Obama administration. If you look at a credit card statement, you’ll see a box that compares how much more you’ll be charged in interest by paying only the minimum each month compared with having the balance paid off in 36 months.

Now that you’ve been tracking your expenses, you should have a sense of what comes due every month. And when you first made your budget earlier in this newsletter course, I told you to start by budgeting only the minimum monthly payment for your debt every month. If you do only that, you’ll pay off your debt eventually — but you’ll pay a lot more in interest on top of it.

This week, we’re going to make an attack plan to pay it down faster.

There is definitely a temptation when you start taking charge of your finances to mobilize every dollar to throw at debt. But, as we’ve discussed, that could be setting yourself up to fail. You want to be making reasonable, sustainable lifestyle changes, not taking a vow to live like a nun until you’re debt free.

Warning: Snow metaphors ahead

There are three popular approaches to tackling debt: snowball, avalanche and blizzard.

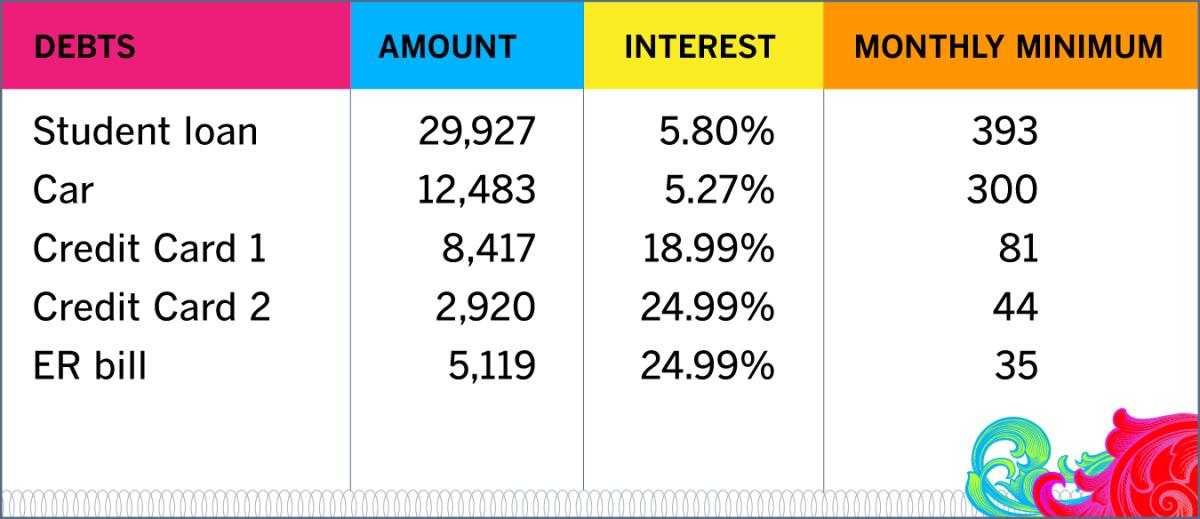

For illustrative purposes, let’s pretend these are your debt balances, the interest rates and the minimum amounts you need to pay on them each month.

How it would work using the snowball method: Order your debts from smallest to largest. That means credit card 2, then the ER bill, then credit card 1, then the car, then the student loan. Pay the minimum on all of them every month, and throw whatever extra you can at that smallest debt first until it’s paid off. Then “snowball” that minimum payment into the extra you throw at your next debt, working your way up to the highest balance. So you’d take the $44 you were putting every month toward credit card 2 and add it to the ER bill minimum.

How it would work with the avalanche method: Order your debts from the highest interest rate to the lowest. Use extra to pay off the highest-interest debt first and then apply that minimum to the next highest, and so on. That would mean the ER bill first, then credit card 2, then credit card 1, then the student loan, then the car. After paying off the ER bill, you’d throw at least that extra $35 minimum per month at credit card 2.

There are pros and cons to these approaches. With the snowball, you get the quicker psychological win of getting a debt completely paid off. I like a win. With the avalanche, practically speaking, you save money in the long run by getting rid of higher-interest debt first. It makes more sense from a mathematical perspective. (The popular tool Undebt.It has a calculator to see how much time and money either approach will take you. Depending on which budgeting software you’ve decided to use, there might also be some kind of loan management tool you can access there.)

But if your higher-interest debts are also your highest-balance debts, you wind up juggling a lot of monthly payments, and you might get discouraged if you’re never approaching zero anywhere.

The “blizzard” method combines the two. Take one or two smaller debts and focus on those first. Getting those balances to zero means you can take an entire line item or two off your budget and start throwing the minimum at other debts. Then start on the high-interest debt.

None of these methods are right or wrong. The right approach is the one you’ll stick with. Don’t discount the power of those quick wins! One of the first things we paid off was a personal loan my husband used to consolidate his credit card debt. The interest was low, but it was a massive monthly minimum payment. I wanted to claw those dollars back to attack my other priorities.

With this eight-week newsletter course from the Los Angeles Times, assistant editor Jessica Roy will help you get a handle on your money stuff.

Negotiate your bills and interest rates

Debt and money are fake. I mean, OK, they’re real. You have money and you owe money. But things such as interest rates and due dates and totals are a lot more flexible than you might realize.

For instance: Did you know that you could call your credit card company and ask them to lower your interest rate? And they probably would do it? Seriously. Here’s a script: “Hi, I’m a current customer, and I’m reviewing my monthly spending, and I was just wondering if I was eligible for a lower APR on this card.” On multiple occasions when I did this, the answer was, “Oh, yes, you are,” and they’d shave a few points off.

Due dates are also not set in stone. I realized part of the reason I felt so rich half the month and so broke the other half was that all my bills happened to fall in the last two weeks of the month. We paid rent on the 15th and everything else between then and the 1st of the next month. But you can change your due dates on bills. Go onto the website for your credit cards and utilities, and some of them will let you move the due date from there. If it doesn’t let you, call and ask.

Do you have medical debt? Those numbers aren’t real either. NPR has a great guide to negotiating that.

Also, how old is your debt? It might be past the statute of limitations for when it can be collected.

Personal loans and refinancing

For credit cards or other smaller personal debts (if you financed buying a mattress, for instance), you might want to look into a balance transfer or personal or debt consolidation loan. Some personal finance gurus hate those types of loans, where you consolidate your debt into a loan that charges less interest (but usually much higher monthly minimums, since it’s a loan as opposed to a line of credit). The aversion goes like this: You pay off your high-interest credit card debt using a lower-interest consolidation loan, but then you have all that spending power on a credit card tempting you to run up more high-interest debt. I agree — you don’t want to do that. But you’re a budgeting person now who only spends money you already have.

Balance transfers are basically just opening a new credit card and rolling your existing balance onto it. This is what I did. I saved a ton of money by transferring my balance to a new card with a 0% introductory interest rate for 18 months. I divided the total by 18 and paid off exactly that much every month, so the whole thing was paid off without accruing any more debt (beyond the initial 3% transfer fee).

There are lots of places online to compare balance transfer offers and debt consolidation loans and refinancing. For a balance transfer, you want to figure out both the new interest rate and the balance transfer fee, and calculate what you’ll have to pay per month to get rid of your debt before the introductory period ends and interest starts to rack up again. NerdWallet, Bankrate and U.S. News & World Report all have solid recommendations for places to start looking.

For debt consolidation loans, you want to make sure the interest rate is lower than what you’re paying now, there aren’t hidden or ultra-high fees, and that you can afford the new minimum. Credit Karma has a good guide to evaluating whether a debt consolidation loan is right for you. U.S. News & World Report has a guide to choosing a debt consolidation loan and ranks what it considers to be the best companies, as do Bankrate and NerdWallet.

Compound interest is pernicious — it can feel as though no matter how much you’re throwing at your debt, you’re getting sucked back down. Anything you can do to reduce what you rack up every month is a good thing. Make sure you’re looking at both the interest rates and the upfront costs such as balance transfer fees as you compare.

One thing not to do (Never ever! Not even once!!) is take a super-high-interest personal or payday loan. They are immensely tempting, and they are extremely bad news that will almost always leave you in a worse financial position than when you started. A personal loan with an APR lower than your current debt: potentially OK. A personal loan with an APR higher than every other debt you have: avoid, avoid, avoid.

For big-ticket debts such as student loans and mortgages, it is worth looking into what your refinancing options are. I am not recommending any specific products or services here — I have not personally refinanced either of those types of loans. But you have a lot of options, and it’s worth exploring them to see if you can save in the long run. Again, NerdWallet, Bankrate and U.S. News & World Report are all very good places to explore your options and see what experts recommend.

What about debt settlement or bankruptcy?

If you’ve run your numbers every way you can and there’s just no way to make ends meet and pay down your debt, it might be time to consider a drastic step such as filing for bankruptcy. There are companies out there that say they’ll work with your creditors to reduce the amount you owe or help you through bankruptcy. I am not an expert on these.

But Liz Weston, a certified financial planner whose personal finance column appears in the L.A. Times, is. So I will paraphrase her advice: Be very careful about whom you choose to help you. Consulting the National Assn. of Consumer Bankruptcy Attorneys for a bankruptcy attorney, or a nonprofit credit counseling agency (the FTC has a guide), should be your first step.

Can I still use my credit card while I’m paying down my debt?

If you couldn’t afford to pay off your credit card balance in full with the money that’s in your bank right now, you are carrying a balance, which is debt. (Yes, even if you’ll be able to pay the balance in full by the time it’s due because it’s after you get paid again, you are still buying things with money you don’t have yet.)

Some people prefer to use their credit card for the purchase protection that it offers, or to take advantage of cash-back and other rewards. To me, the rewards argument isn’t a very good one. Credit card “rewards” aren’t really rewards if you are paying interest every month. Earning 3% cash back is pretty paltry if you are getting slammed with an 18% APR. But if you’re renting a car or making a major purchase, I understand wanting the protection of a credit card over a debit card.

Personally, when I was paying down debt, I knew I needed to distance myself from the allure of my easily gotten credit. I didn’t literally freeze my cards in a block of ice, but I took them out of my wallet and put them in a box under my desk. I would bring one with me when I traveled, in case of emergencies and for things like the refundable deposit on a hotel or rental car, but otherwise they stayed home.

Traditional wisdom is that if you have debt — even if it’s just a couple weeks of expenses that you will be able to pay off soon — you should stop using credit cards entirely. But I don’t think that’s the right fit for everyone.

You have to make your own call here. Are you responsible enough to use your card only for things you could buy in cash right this second? Do you have enough willpower to resist the temptation to run up an open line of credit you’ve worked so hard to pay down? Are you the sort of person who says, “Things are tight and it’s the last weekend of the month, so let’s throw this bar tab on the credit card and worry about it later”? Later is now. Be accountable for that bar tab.

Next week: Fun

Next week, we’ll talk about something significantly more fun: saving up for something like a vacation or wedding. Right now, I bet you’ve got some phone calls to make.

Good luck, and see you next week.

— Jessica

P.S.

This newsletter is free. But making it is not. Totally Worth It won’t have any sales pitches for specific financial products — i.e., I’ll never tell you that you need to buy this specific software or open an account with this specific bank. My only sales pitch is this one: If you aren’t already, please consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times. For a budget-friendly $1, you can try it out for a limited time.

Thoughts? Comments? Email [email protected]. And to ensure you get this newsletter, please add this email address to your contacts or address book. Thanks.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.