Column: Why health insurance companies will solicit you even after you die

- Share via

Being dead hasn’t stopped Martin Siegel from being a solid insurance prospect.

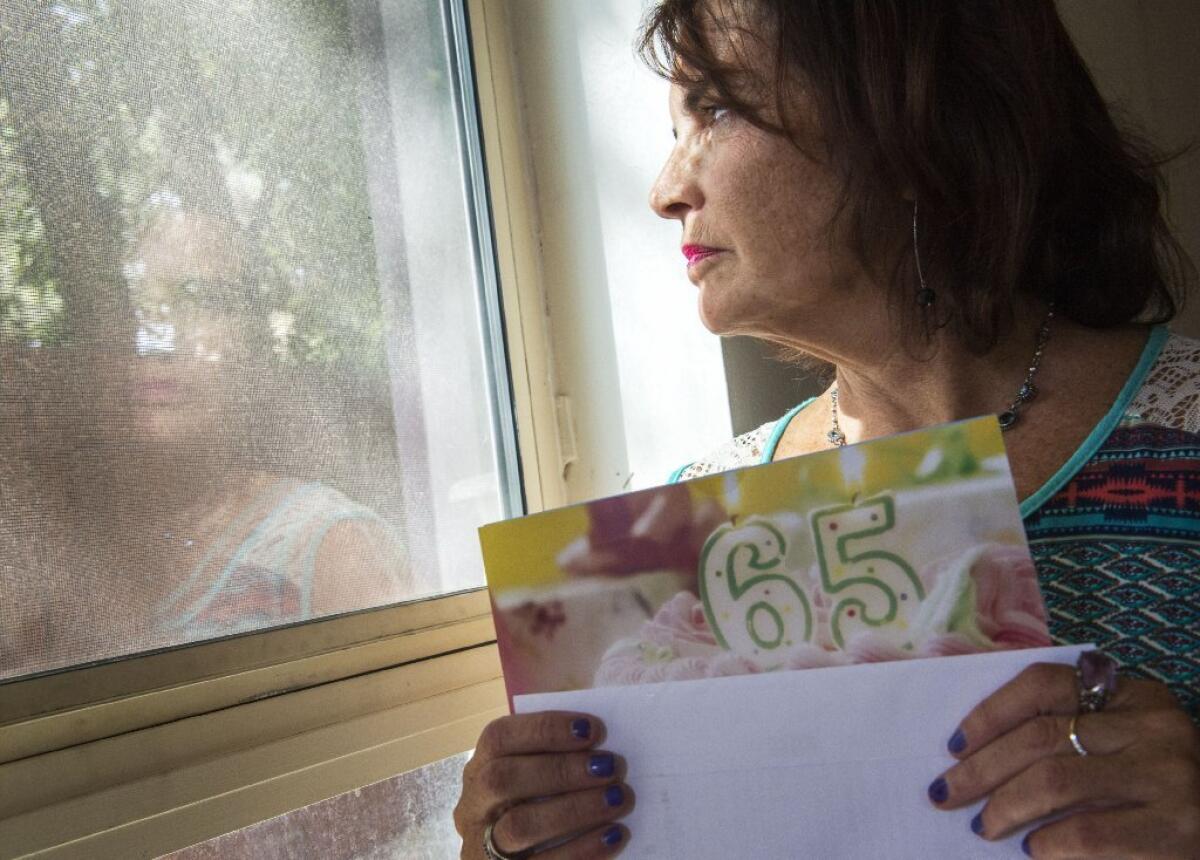

Siegel, who died in 2002, would have turned 65 this year. As such, he’s received solicitations from UnitedHealthcare, Kaiser Permanente and other insurers trying to sign him up for Medicare Advantage plans.

“It’s just about every insurance company you can think of,” said Geri Siegel, his widow.

“I receive his Social Security in my name, so the U.S. government obviously knows that he has been deceased for 14 years,” the Encino resident said. “How could something like this happen?”

The answer to that question leads us into the murky world of “big data,” in which people’s personal information is bought, sold and shared by public and private entities.

One wrong data point can have a cascade effect throughout the cyberverse, creating erroneous files in potentially thousands of databases. I have some tips below.

Bad data is how a fraud victim’s credit score can remain battered even after attempts have been made to address the fallout from identity theft. It’s how junk mail can keep arriving long after a consumer has made his or her preference known to a business. It’s how marketers can pursue a dead person.

“Databases are far from perfect,” said Peter Swire, a professor of law and ethics at Georgia Tech’s Scheller College of Business and former chief counselor for privacy in the U.S. Office of Management and Budget. “At my house, I still get lots of mail for previous residents. That’s the marketing system in our country.”

Last week, I wrote about how big data is raising privacy questions in the healthcare field and looked at the likelihood of a national database of people’s DNA. Those are serious matters.

But even relatively minor annoyances such as unwanted catalogs filling your mailbox can reflect the pervasiveness of big data and the frustrating sense of powerlessness that can come when dealing with automated systems.

“There’s a lot of inaccurate information floating around, and it can be very hard to say where a company got it,” said Joel Reidenberg, a law professor and director of Fordham University’s Center on Law and Information Policy.

In Siegel’s case, I spoke with both the Social Security Administration and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Representatives of both agencies said they don’t make beneficiaries’ — or soon-to-be beneficiaries’ — contact information available to marketers.

I asked the various insurers involved how a man who passed away 14 years ago had gotten onto their mailing lists. None wanted to offer specifics.

Taylor Joseph, a UnitedHealthcare spokesman, said only that “our address information is compiled from several publicly available sources.”

Sandra Hernandez-Millett, a spokeswoman for Kaiser Permanente, said that “we use a variety of publicly available sources to purchase consumer data, which we acquire both through list brokers and directly from the list owners.”

Here’s where things get frustrating for consumers. Who are these list brokers and list owners?

As for the latter, list owners are all sorts of businesses, particularly those that rely on memberships or subscriptions, such as publications and telecom firms. Yes, that would include the Los Angeles Times and just about every other newspaper and magazine.

Selling customer and subscriber lists is a way companies generate extra cash. It’s been going on for decades.

List brokers are companies that buy and sell lists of consumer info. They operate mainly in the shadows, and this is why it’s so difficult for consumers to correct bad info. Tracing an error to its source is practically impossible.

In 2003, California passed a “Shine the Light” law requiring businesses to disclose sales of customer information. However, it doesn’t require businesses to say where they buy info.

I did a Google search for “lists of people turning 65,” which is presumably how the insurers ended up pitching the late Martin Siegel. My search returned more than 7 million results, and the first few pages at least were primarily list brokers.

Here was InfoUSA, which boasted that its lists “are an ideal choice for any business looking to target individuals nearing retirement or those needing Medicare supplement leads.”

Here too was Dataman Group, which said the people on its lists “are great prospects for Medicare supplement policies as well as other insurance products and are best reached via direct mail.”

Each insurer I spoke with expressed regret that Geri Siegel had the painful experience of receiving mail in her deceased husband’s name. And each pledged to immediately scrub him from their lists.

But that doesn’t solve the problem. Without knowing how the lists were generated or where they came from, Martin Siegel lives on in marketing purgatory. His name and address are still for sale.

“Consumers should be able to find this out,” said Beth Givens, executive director of the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse in San Diego. “But there’s no way to follow the bread crumbs.”

She said consumers are left to play Whac-a-Mole, contacting businesses individually to be removed from their mailing lists. Beyond that, there are some broader steps people can take.

To stop unwanted credit card and insurance offers, go to OptOutPrescreen.com. The site is run by the top credit-reporting companies and allows you to opt out on an industrywide basis for five years. To opt out permanently, you’ll need to mail in a signed form.

A site called DMAchoice.org, operated by the Direct Marketing Assn., lets you to put a halt to credit card offers, catalogs, magazine-subscription mailers and other pitches from about 3,600 companies and organizations belonging to the industry group.

And don’t forget the federal government’s do-not-call list, which is intended to keep telemarketers at bay. Reputable companies typically will respect your preference. The bottom feeders probably won’t.

David Lazarus’ column runs Tuesdays and Fridays. He also can be seen daily on KTLA-TV Channel 5 and followed on Twitter @Davidlaz. Send your tips or feedback to [email protected].

MORE FROM LAZARUS

DNA database could help predict your disease — then get you fired

‘Big data’ could mean big problems for people’s healthcare privacy

Frontier still struggling to put Verizon takeover issues to rest

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.