Writers work picket lines as TV shows shut down

- Share via

In an often spirited display of protest playing out on both sides of the country, more than 1,000 screenwriters -- representing “Lost,” “The Young and the Restless,” “Chinatown” and everything in between -- hoisted picket signs and chanted labor songs as a long-feared show business strike became a potentially crippling reality Monday.

In their first full day away from their computer keyboards, the Writers Guild of America members scored several important victories. And those who are not on the picket lines -- primarily television’s so-called show runners -- found themselves figuratively on the line, wrestling over whether to return to work.

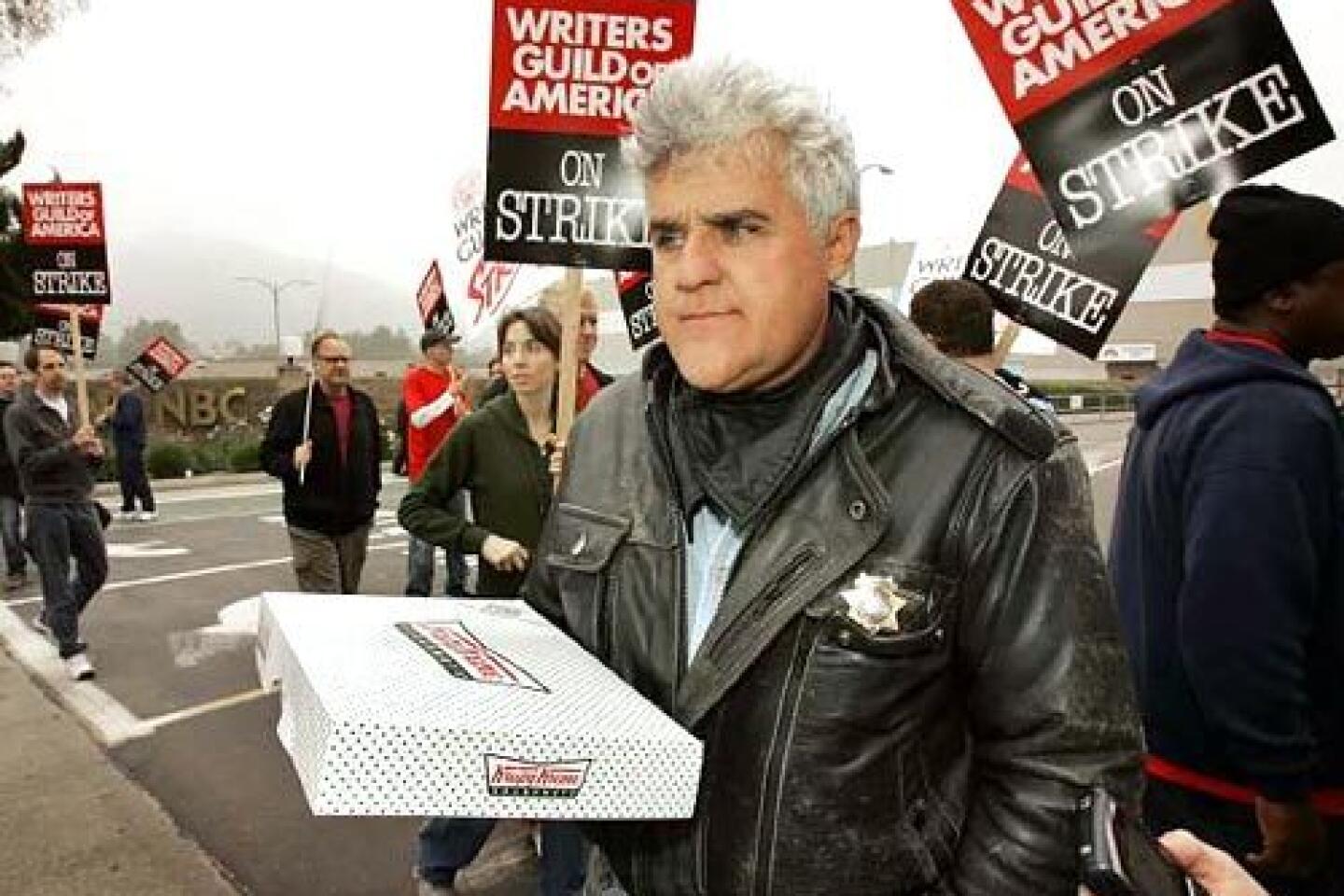

The makers of “The Tonight Show With Jay Leno,” “The Daily Show With Jon Stewart” and “Late Show With David Letterman” said they were suspending production of new episodes. Steve Carell, the star of NBC’s hit “The Office,” refused to cross WGA picket lines, and Ellen DeGeneres, the host of the syndicated talk show “Ellen,” decided against taping her show in a gesture of solidarity.

CBS said production on its comedy “The New Adventures of Old Christine” was halted, and ABC said it was delaying the premiere of the series “Cashmere Mafia.” At the risk of losing their jobs, some members of Teamsters Local 399 decided not to cross the picket lines, and that action might have shut down a small number of shows, union officers said.

More ominous, perhaps, was the sudden suspension of special deals that studios extend to star writers. Fox and CBS began notifying some of their top talent that they would stop paying for staff and development, a tactic other studios were considering.

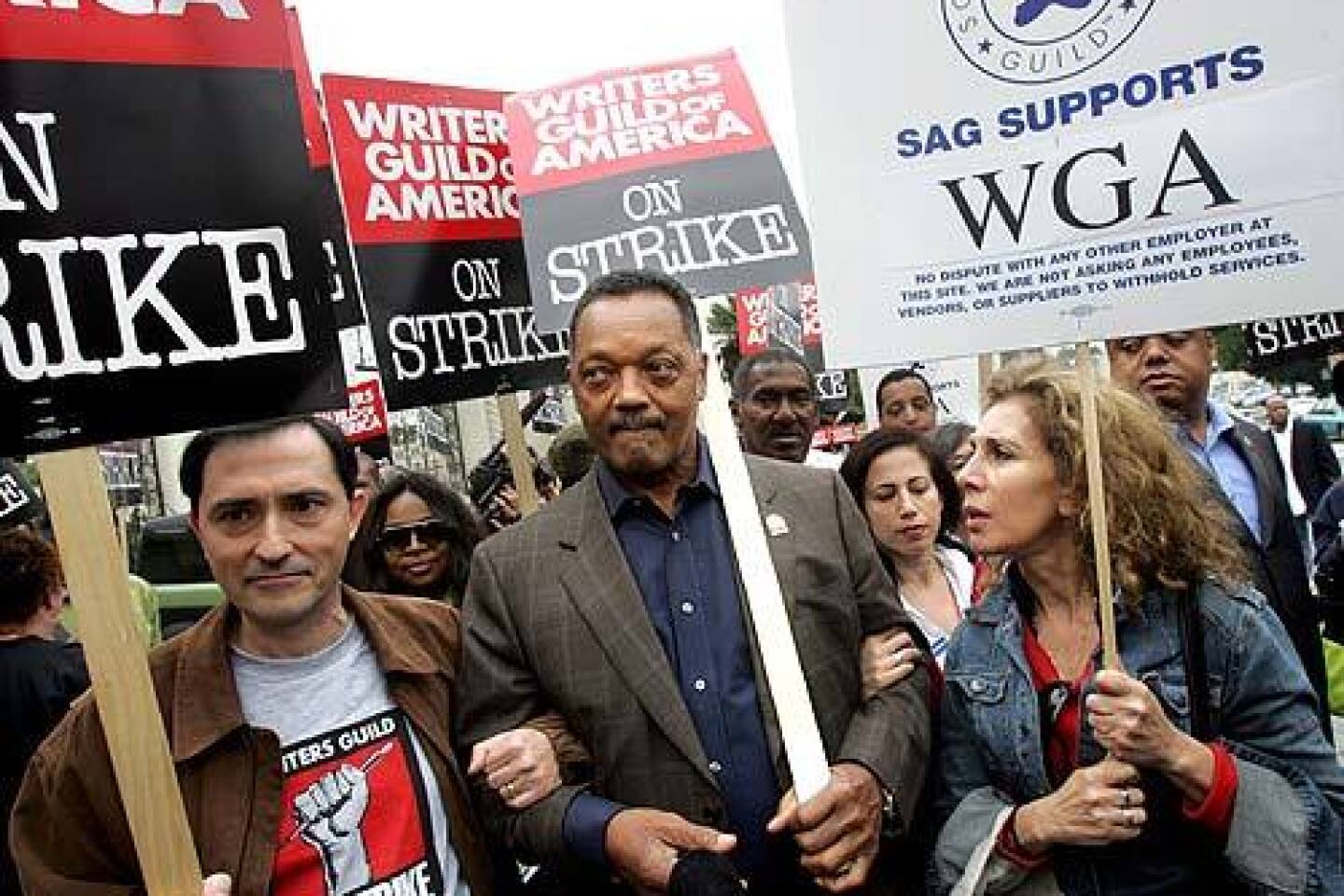

Less than 12 hours after negotiations between the WGA and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers collapsed in a West Hollywood hotel meeting room Sunday night, WGA members launched boisterous demonstrations against the major movie and TV studios in Los Angeles and New York, with several top performers visiting the front lines to lend support.

The suddenly out-of-work Leno handed out doughnuts to writers picketing NBC’s Burbank studio. “I don’t know what we’re going to do. I don’t know how long it is going to last,” Leno said as he distributed boxes of Krispy Kremes. “I’ve been working with these people for 20 years. Without them I’m not funny. I’m a dead man.”

The daylong rallies, scheduled to run until further notice, appeared designed to galvanize the union’s resolve -- the last WGA strike in 1988 lasted 22 weeks and cost the industry an estimated $500 million -- and rally support for the WGA’s bargaining position.

“You want people to be aware of what’s at stake,” Carlton Cuse, a writer and executive producer on ABC’s “Lost” and a member of the WGA’s negotiating committee, said as he took up a picket sign in front of the gates of his employer, Walt Disney Co. “We are the primary creative artists in this medium.”

Regular viewers of late-night television will immediately notice the disappearance of their favorite shows, but television dramas and comedies, whose scripts are written well in advance, will continue to appear as programmed for weeks if not months to come. Movies, which often take two years to produce, will arrive in the multiplex as scheduled for at least the next year.

Several issues divide the 10,000-member WGA and the producers, but the most contentious point is supplemental payments, or residuals, for TV series and movies shown on computers and new-media devices such as cellphones and video iPods. No contract talks are scheduled between the sides.

“If you look at iTunes, ‘Hannah Montana’ and several other Disney shows are among the most avidly downloaded shows -- they are hugely successful on the Internet,” Steven Peterman, an Emmy-winning “Murphy Brown” writer and “Hannah Montana” executive producer said as he picketed Disney. “And we make no money from that -- zero.”

Nick Counter, the president of the producers alliance, said he was disappointed that the WGA had gone on strike. “A strike is obviously painful for all involved. It costs the companies money and it costs the writers money.”

If screenwriters feel they receive scant appreciation from the networks and studios, the people uttering their lines in front of the cameras were openly supportive. In apparent violation of Screen Actors Guild rules saying actors are obligated to show up to work during a writers strike, Carell refused to cross picket lines to work on “The Office,” according to an NBC source.

In front of Paramount Pictures, “Dirty Sexy Money” actor William Baldwin served coffee and joined the picket lines. In New York, “Saturday Night Live” comedian Amy Poehler joined a large contingent of writers and actors from the show on the picket line in front of the Rockefeller Center offices of NBC, a subsidiary of General Electric Co.

“All the writers are asking for is to be fairly compensated for all this new media,” she said, noting that the strike may force the cancellation of this coming week’s show with Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. Poehler, like many “SNL” cast members, contributes material for the program but is not listed as a writer. She said actors felt torn about the labor impasse. “I think a lot of actors are being made to make some really hard choices,” she said.

Also caught in the middle of the walkout are the TV show runners, who serve as both writers and executive producers. As WGA members, they are obligated to stop writing; as producers, they have to ensure that the show somehow goes on.

Warren Leight, the show runner of USA Network’s “Law & Order: Criminal Intent,” was wrestling with that very issue on the picket line. Just before the strike began Sunday at midnight, Leight faxed in a “Criminal Intent” rewrite. Although Leight said he would not write another word until the strike was over, he may be called upon for his input on editing and other responsibilities he has as a show runner. “I’m trying to figure it out,” he said.

What’s not as complicated, Leight said, is the need to strike. “They made us an offer we had to refuse,” he said of the studios. “My sense is they wanted it to come to this.”

In one sign of the tough tactics likely to be employed, some of the major television studios began telling star writers Monday that their compensation for staffing and development was being suspended.

News Corp.’s Fox and CBS Corp.’s television studio were sending such letters concerning what are known as overall writing deals and pod production deals, people familiar with the moves said.

Though it’s logical to stop paying special salaries to writers who are on strike, agents and executives said they were surprised the suspensions came so quickly.

More serious, they said, was the suspension of pod production deals, which give development money to writers and producers. Cutting that money will quickly force layoffs of nonwriters, including producers, assistants and secretaries.

Despite the gravity of the dispute, the mood on the picket line was often convivial. In New York, three members of Local 802 of the Musicians Union, outfitted with trumpet, trombone and French horn, serenaded the strikers. In Los Angeles, striking screenwriters chanted, “Network bosses, rich and rude, we don’t like your attitude!”

The atmosphere “has been incredibly supportive,” David Abramowitz, a strike captain and “MacGyver” screenwriter, said outside CBS’ Radford studios in Studio City. “I’ve been in the guild for about 26 years, and I’ve never seen it so united.”

Exhausted after walking the picket line on crutches, “Simpsons” screenwriter Mike Scully said he was taken aback by the outpouring of public support, most of it voiced in shouts and honking horns from passing cars. “I’m surprised by just how behind us people seem to be so far,” he said. “I wouldn’t blame people for not caring or understanding what the issues are.”

The picket lines were filled with A-listers and anybodies.

“It really doesn’t matter what business you are in if the living you make is threatened,” Robert Towne, the Oscar-winning author of “Chinatown” said outside Sony.

“A strike is like war in a way: Nobody wins but they are also sometimes unavoidable. I guess this is unavoidable.”

Picketing alongside Towne was a fellow Oscar winner, writer and director Paul Haggis. The “Crash” filmmaker called the current dispute with producers “another example of corporate greed.” He accused them of trying to “shut down the entire town,” and said he was prepared to walk the picket line for as long as it took.

Walking in front of the Paramount gate was first-time screenwriter Matt Lazarus, who officially joined the WGA in July. The 23-year-old high school dropout from Vermont made his first writing sale in May with a remake of 1945’s Boris Karloff movie “Isle of the Dead.”

“I’m the youngest guy on this line. It’s easier for me to be out here because I’ve got to live with this contract much longer than anyone else here,” Lazarus said. Still, he said, his first script sale didn’t bring him a huge payday and he may have to take a night job in a couple of months to support himself. “I’ll survive; I’m young,” he said. “I don’t have a wife, kids or a mortgage.”

Many other writers do, and that could prove disastrous.

Although top screenwriters like Haggis can make as much as $250,000 a week, many WGA members collect middle-class wages and can go months between jobs; the threat of an extended work stoppage could have grave consequences for the industry’s lesser lights.

Bernard Lechowick, a writer for “The Young and the Restless” who struck for 22 weeks in 1988, said he expected the financial loss to be difficult.

“It’s a huge stress when you lose your income, which I did starting today,” said the longtime television writer and executive producer. “But what would be worse is to take a lousy contract. When you sign up for a job in Hollywood, you’re guaranteeing yourself irregular employment. And if there’s one thing this industry teaches you, it’s to budget.”

Adam Armus, 43, a writer and producer on “Heroes,” said at Sunset Gower Studios that he had a long talk with his 4- and 7-year-old daughters, telling them that Christmas was going to be different this year.

“Normally at this time of year, we would be going shopping, but I’ve had to explain that Daddy is fighting for them right now,” he said.

“We’re going to have to make some sacrifices this year so that we can have a better Christmas next year. And they totally understand.”

Times staff writers Kate Aurthur, Greg Braxton, Andrea Chang, Maria Elena Fernandez, Matea Gold, Chris Lee, Meg James, Joseph Menn, Martin Miller and Robert W. Welkos contributed to this report.

WRITERS STRIKE Late-night drama in two time zones Talks in West Hollywood ended abruptly when the strike began on the East Coast. Business, C1

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.