Salinas hopes to turn farm workers’ children into computer scientists

- Share via

SALINAS, Calif. — Dario Molina’s alternative life scrolls by on both sides of Highway 101 north: acre upon acre of lettuce, spinach, heartbreak.

Not me, he thinks. Not anymore.

“Sometimes I reminisce,” Molina says. “Damn, I remember working in that field. I remember that heat ... that song. Now I’m just thinking, I just want to get over this.”

He tucks a water bottle between his back and the driver’s seat of his 1996 Civic to keep his lumbar muscles from stiffening as towns drift by: Greenfield, Soledad, Gonzalez, Chualar. Each as poor as the next. He turns east on an old farm road, then north, until the fields wash up against the east side of Salinas.

There, at Hartnell College’s Alisal campus, Molina settles behind his laptop, deft fingers furiously typing code like they were still plucking chiles, feeding bucket after bucket onto a packing machine that advances steadily on his heels.

He’s there by 8:30 a.m., 15 minutes early for his first class. He’ll stay until 10 p.m., later if they didn’t kick him out. Weekends when he can. Holidays.

Dario Molina, 22, is in a hurry to outrun his past.

So, too, is Salinas.

::

Salinas hopes to turn the sons and daughters of farm workers into coders for the next generation of data-driven, automated farming in a valley known as the salad bowl of the world.

With one foot in its fields and another edged toward Silicon Valley, Salinas is trying to reboot itself as the agricultural technology center of California. It hopes to turn the sons and daughters of farmworkers, like Molina, into coders for the next generation of data-driven, automated farming in a valley known as the salad bowl of the world.

“We’re not trying to reinvent ourselves,” said Andrew Myrick, the city’s economic development manger. “There’s cities all across the country that are trying to attract Google to come and build their headquarters. That’s not who we are. We’re agriculture.”

No public high school in the Salinas valley taught computer science and only a sliver of Salinas’ workforce worked in computer science for a living when the ag-tech idea took hold here about four years ago. Capital One had just bought out the city’s largest private employer, HSBC, putting about 900 people out of work.

“That’s when we said, “Well, what else do we really need to do to strengthen our economy so this doesn’t happen again?’” City Manger Ray Corpuz said. “That’s when we said we need to build around agriculture, ag-technology.”

See the most-read stories this hour >>

Andy Matsui, a Japanese immigrant who turned 50 acres into a fortune in orchids, kicked in $2.9 million to start a three-year computer science program at Hartnell College and Cal State Monterey Bay. That program has since coalesced with others in what now is known as the Steinbeck Innovation Cluster, named for Nobel Prize-winning author John Steinbeck, who grew up here.

Matsui is not the only major grower stepping up to help. Native son Bruce Taylor, chief executive of Taylor Farms and a scion of the Church lettuce family, placed a $40-million bet on downtown last year when he opened a new corporate headquarters a quarter of a mile from skid row.

“In the 59 years that I’ve lived here, downtown has continued to go downhill,” Taylor said. “We had an opportunity through the success of our business to maybe change the trajectory and to make a positive impact on the future of Salinas.”

The new 2,800-square-foot Western Growers Center for Innovation and Technology in Old Town Salinas houses startup technology companies.

On the bottom floor of the five-story French Colonial building is the centerpiece of Salinas’ ambitions: the Western Growers Association Center for Innovation and Technology, which hopes to create the first wave of ag-tech start-ups. Ten have taken up residence so far — offering drone and satellite-based imaging, soil sensors, solar energy controls, app-based data management and other tools for a burgeoning “precision agriculture” movement.

High hopes have been dashed here before. The National Steinbeck Center, across the street from Taylor’s headquarters, was founded amid similar optimism in 1998, but now is a dollar-a-year tenant in its own building, which the city sold for $3 million to Cal State Monterey Bay. (The university does not plan to hold any regular college courses there.)

Banners across the front of the center tout Salinas’ ambitions to be a “City of Letters,” though it is the government center of a county where 28% of residents lack basic literacy skills, according to the Panetta Institute for Public Policy.

NEWSLETTER: Get essential California headlines delivered daily >>

Steinbeck himself was not charitable about his childhood home. “The mountains on both sides of the valley were beautiful and Salinas was not, and we knew it,” he wrote in 1955. For the native son who set several novels here, the town founded on a high spot amid salt flats had “a blackness that seemed to rise out of the swamps.”

The unflattering portrait stung then and haunts the city now. Salinas just ended its most deadly year for murders — 39 of them, clustered in the east side area where Molina attends computer class. Most were Latino, male and young — the median age in the city is under 29, far younger than the state average. One in five of Salinas’ 157,000 residents lives below the poverty level, and the average per capita income was $17,810 in 2014 — 40% lower than the state’s median, according to U.S. Census data.

“I understand what’s going on — I don’t have to like it,” said Mayor Joe Gunter, an ex-cop who, like many here, wears his heart on his sleeve when it comes to his city. “Sure, we’ve had some issues; we’ve had some tough times. But what makes our community strong is the people. It has nothing to do with who’s got the money.”

A pedestrian is reflected in a storefront window as he walks down Main Street in the Old Town section of Salinas, Calif. City officials are hoping that the recent opening of Taylor Farms’ $40-million headquarters will help revive downtown.

Those who have the money have largely eschewed Salinas’ downtown and east side. They choose north Salinas or the gated communities springing up on the highway leading toward the wealthy Monterey Peninsula. Just 1.8% of Salinas’ population earns more than $200,000 a year, and they’re clustered in the north and northeast side of town, according to the U.S. Census. The median household income in East Salinas and downtown, meanwhile, is under $40,000, about 35% below that of the state.

The disparities raise thorny questions for a quintessential agricultural town whose wealth and poverty spring from the same root of cheap labor.

“Is that just a separate segment, a rented part of the community that comes in to pick our fields, and gets replaced or is expendable? Or is it our community?” said Tim McManus, lead organizer of Communities Organized for Relational Power in Action, an umbrella group that is addressing Salinas’ endemic poverty, crime and other socioeconomic troubles.

Although agriculture is the town’s economic engine, almost 20% of Salinas’ workers are employed in the service industry, with more than half of those jobs in food preparation or grounds maintenance, according to U.S. Census figures. About 25% of Salinas’ workforce toils in the 369,187 acres of crops such as lettuce, strawberries, vegetables, grapes and flowers that generated about $4.5 billion in revenue in Monterey County in 2014.

Those workers are finding Salinas too expensive. Nearly half of renters dedicate 35% or more of their paychecks to pay rents that are only about $57 to $116 less than rents in Los Angeles, according to U.S. Census and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development data. A three-bedroom home actually is slightly more expensive in Salinas, according to HUD. Growers throughout the valley complain of a shortage of workers that has worsened over the last several years.

::

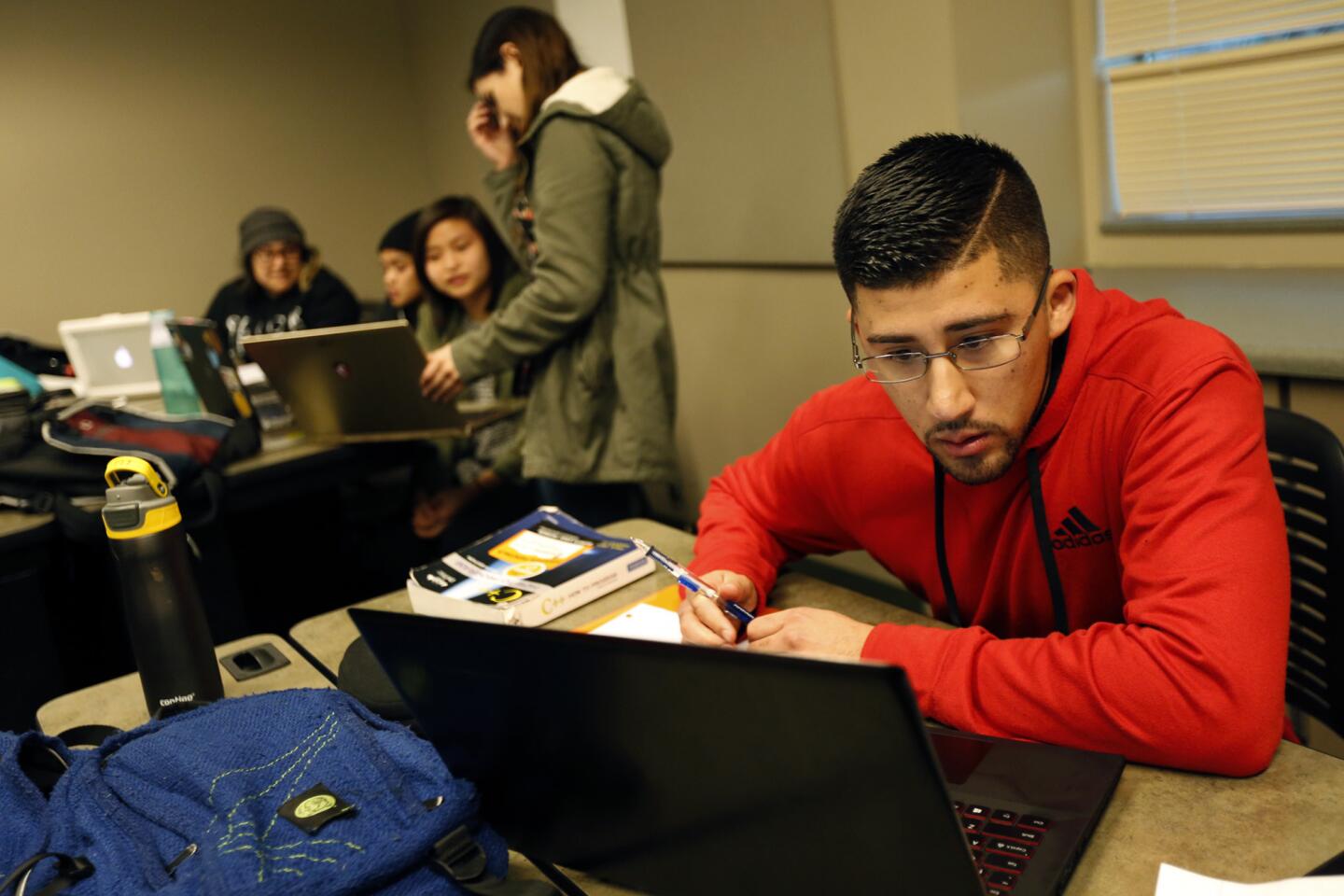

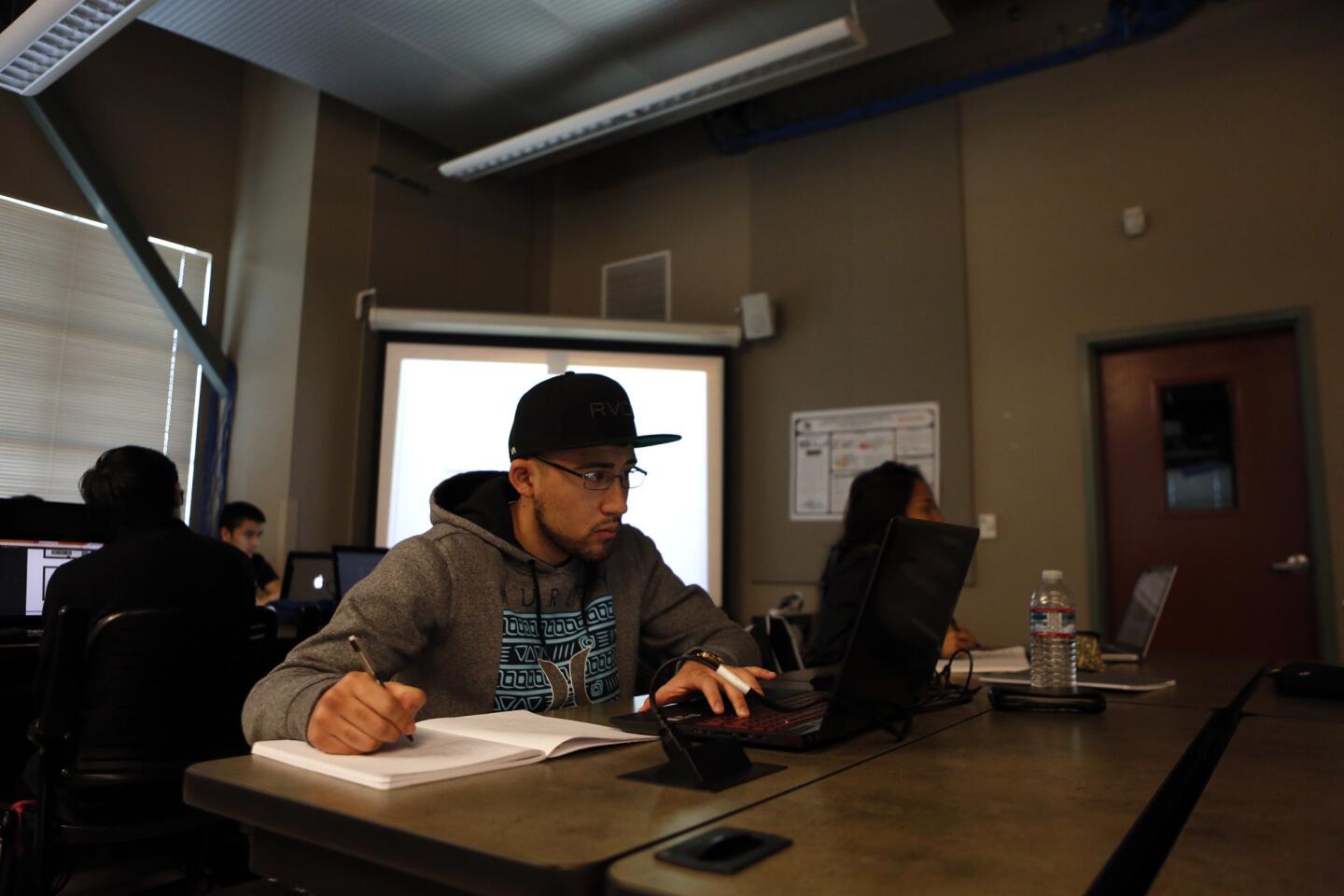

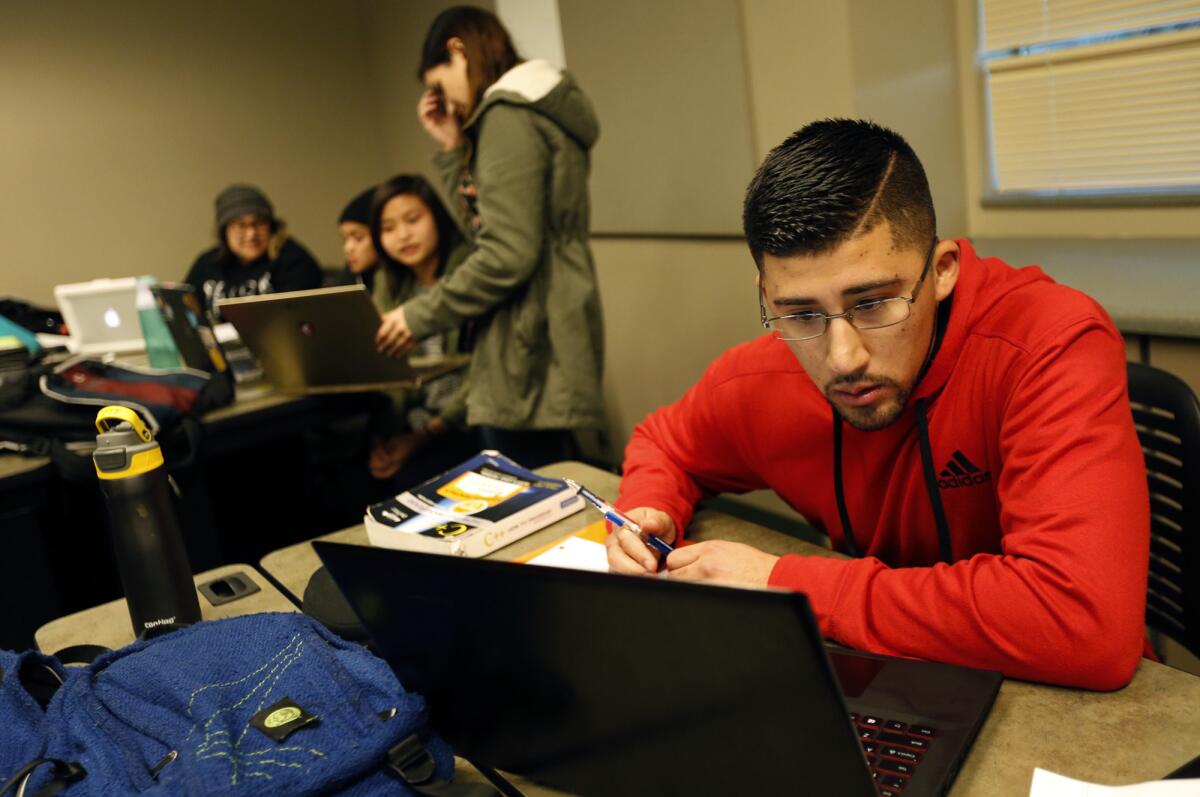

After classes, Dario Molina, 22, works on assignments during a study hall at Hartnell College Alisal Campus in Salinas, Calif.

Dario Molina can’t afford Salinas. He pays $200 a month to share a home with two friends in King City, Calif.

From the second grade until high school, the El Centro, Calif., native moved around with his family as they followed crops from Yuma, Ariz., to California’s Imperial Valley, to the Salinas Valley.

Two days after graduating from King City High School, he faced a deadline set by his stepfather — contribute to the rent or go fend for yourself. Molina left. He spent a few nights sleeping under a highway bridge and many months on the spare beds and couches of friends. He worked fields, where he injured his back, fast-food restaurants and a supermarket before enrolling at Hartnell College, where his math skills attracted the notice of the computer science program.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

“Now, I appreciate having food and being able to eat,” he said. “There were times I would just drink a lot a lot of water. A lot of water. To calm my hunger.”

Last year, Molina was one of 36 students awarded a Matsui Foundation scholarship to the new computer science program, which crams a four-year computer science curriculum into three years.

Late last semester, he sat in the final coding class taught by Joe Welch, a 58-year-old retired Navy engineer who believes that Alisal, the original name for Salinas’ east side, has “magic and grit.”

On this day, Welch focused on the grit. Employers won’t care where you’re from or that you got your degree in three years, Welch warned. They’ll care whether you can code.

“We won’t coddle you,” he warned. “We won’t give you a participation certificate.”

Hartnell College’s program has an 84% transfer rate to Cal State Monterey Bay, compared with just one computer science student transfer in 2009, a year before the college began assembling the program, according to the school.

Whether this year’s first graduating class will find jobs in Salinas is anyone’s guess. Just 2% of the current workforce is engaged in computer science and engineering, and most of that is on the hardware and IT support side, not software engineering.

The best hope so far may be HeavyConnect, one of the first start-ups to emerge from Salinas’ innovation cluster. Co-founder Patrick Zelaya, a former John Deere sales executive, said he hopes to hire a handful of the program’s first graduates in May for his company, which will help farmers use big data to improve their yields.

“We want to create jobs in Salinas that are different than the traditional jobs that we’ve had here,” Zelaya said. But so far, the Hartnell students’ talents are “above the level of jobs that exist here today.”

Molina is certain that his future lies in the valley that has nurtured and toughened him.

He listens to Welch’s words, hears the sound of the packing machine behind him. Then he puts his fingers to the keyboard and hunches his stiff back into the task ahead.

MORE FROM BUSINESS

Why your Super Bowl vegetable platter might cost more this year

Top state legislators raise concern about electric grid expansion

Sluggish jobs report raises questions about the direction of U.S. economy

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.