Q&A: Uber’s head of aviation talks about its plan for air transport. (Just don’t call it a flying car.)

It has a driving range of about 62 miles and a top speed of 99 mph. (April 20, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

- Share via

Long-held dreams of science fiction fans to fly around town may be inching closer to reality.

A handful of companies recently revealed plans to make personal aircraft. And last month Uber Technologies Inc. discussed its plan to offer an on-demand air transportation system.

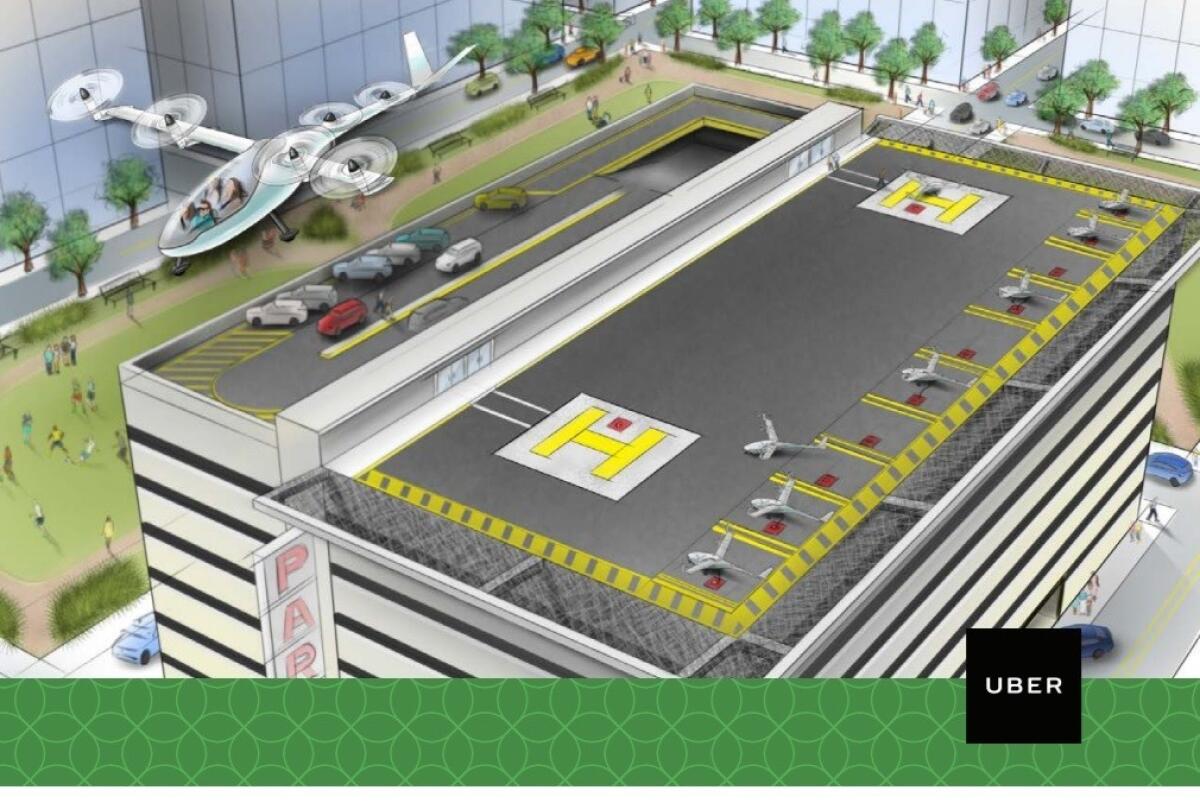

The San Francisco ride-hailing firm envisions customers hailing a car ride to a "vertiport," located perhaps atop a parking structure. An electrically powered aircraft would ferry passengers to another vertiport for a connection with another Uber ground vehicle.

The company has already partnered with five companies that are developing vertical takeoff and landing aircraft, as well as a firm that develops electric vehicle charging systems. At a summit last month in Dallas, Uber said it plans to start tests in 2020 in that city and Dubai, United Arab Emirates, with a goal of initial operations by 2023.

Leading Uber’s effort is Mark Moore, a NASA veteran who was one year away from retirement eligibility when he decided to take the job of director of aviation engineering at Uber. Moore spent his NASA career researching advanced aircraft, with a focus on electric propulsion.

Here is an edited version of our discussion with Moore.

Why come to Uber at this point in your career?

I was at NASA for 32 years, and the entire time I developed vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) aircraft, the technologies and concepts.

The last eight years in particular I have focused on distributed electric propulsion technologies applied to VTOL aircraft and successfully demonstrated and developed three different flight demonstrators. So it was clear to me that the time was right to actually apply these technologies to a commercial market and that they were ready to move forward.

Can you describe what these aircraft would look like? I’ve seen them compared to helicopters.

These are not going to look like helicopters. A helicopter has a single main rotor above the vehicle. For these new aircraft, all of them are using what’s called distributed electric propulsion — instead of having one rotor, they have a bunch of smaller prop rotors which provide the lift.

Some are referring to these as “flying cars.”

I hate the term “flying car” because it’s so misrepresentative. I understand the public embraces it, so I’m willing to tolerate it, but these new aircraft aren’t cars. And we have no intent of ever letting them be on the roadways.

These aircraft will be traveling between 150 and 200 miles per hour in the air. The last thing you’d want is to put this expensive, fast aircraft down on the ground in traffic that’s going 20 miles per hour.

Mark Moore is Uber’s director of aviation engineering.

How is Uber addressing safety concerns?

By designing these aircraft in a redundant fashion with multiple propulsors, multiple engines and multiple controllers, we can fail any single part and, in many parts of the aircraft, multiple parts, and it’s still able to fly and land in a controllable fashion. The minimum number [of propellers] to be able to have one of them fail and still fly safely is six.

A second layer of safety ... is that all these vehicles will be equipped with what’s called a ballistic recovery system — a parachute — so that if some very rare event occurs, the vehicle is able to deploy a parachute and be able to land the occupants on the ground safely.

This technology has been applied to general aviation aircraft, but couldn’t be applied to helicopters because it has that one large rotor overhead. For our new electric VTOL, we don’t have that one big rotor so we’re able to easily deploy this.

Let's talk about how ride-sharing relates to cost.

Ride-sharing is absolutely essential for the economics to work. That’s absolutely essential so these electric VTOL aircraft can be operated with what’s called a high load factor — so that they’re always full of people.

How will this be affordable?

These electric VTOL aircraft are using 10 times less energy than helicopters today, so that energy cost is radically lower.

Also, the maintenance cost is much lower than helicopters because, again, we don’t have any one single-fault parts. If you look at helicopter operations, they have to do really frequent inspections of those fault-critical parts to make sure the vehicle is always safe to fly. If we don’t have any single-failure parts, then we’re able to decrease the maintenance tremendously.

Another factor is these vehicles are highly productive. They’re operating at a speed six times faster than cars on the ground, so they’re able to operate at a higher utilization, over many more hours, than a typical car or a typical helicopter.

[Moore said exact prices won’t be determined until operations begin, but the initial per-mile operating cost would be similar to the price a consumer pays today for UberX — between $1.30 and $1.80. As the aircraft fleet increases and network operations get more efficient, he said, costs could drop.]

What about the cost of a pilot?

The most expensive cost is the pilot for these trips, and that is one of the reasons why we’re pushing toward the future being an autonomous self-flying aircraft. Also, we feel that as the software and the autonomy are proven out, that can be a safer solution than human pilots.

What's the timeline for autonomy?

We’re designing the autonomy into the aircraft from the beginning so that it can be in the background and available and assisting the pilot so that he has a reduced workload.

Right from the beginning, we can be collecting information from every single flight on whether that software is ready to fly the vehicle itself. That lets us just build it into the background and constantly be learning and updating the software.

The FAA is absolutely going to require this, and that we can prove the autonomy is safe by statistically showing them extensive data over hundreds of thousands to millions of hours of operation before we attempt to remove the pilot.

How would you respond to those who say Uber’s timeline is too aggressive?

I don’t think that’s aggressive. It's certainly moving at a rapid pace. To be clear, in 2020, we’ll be operating experimental aircraft in the relevant environment of [Dallas] to prove out that they are quiet enough, safe enough and that the public will accept it. It will not be operational fleets — it will be early test flights that are limited and not passenger service.

I’m positive that it’s very doable and in a very safe fashion.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.