How Trump and an Obamacare rollback could affect the growing gig economy in 2017

- Share via

If you’re accustomed to traditional employment — a steady paycheck, reliable health benefits and a 401(k) with company match — Gabby Golub’s patchwork of jobs might send you into a panic.

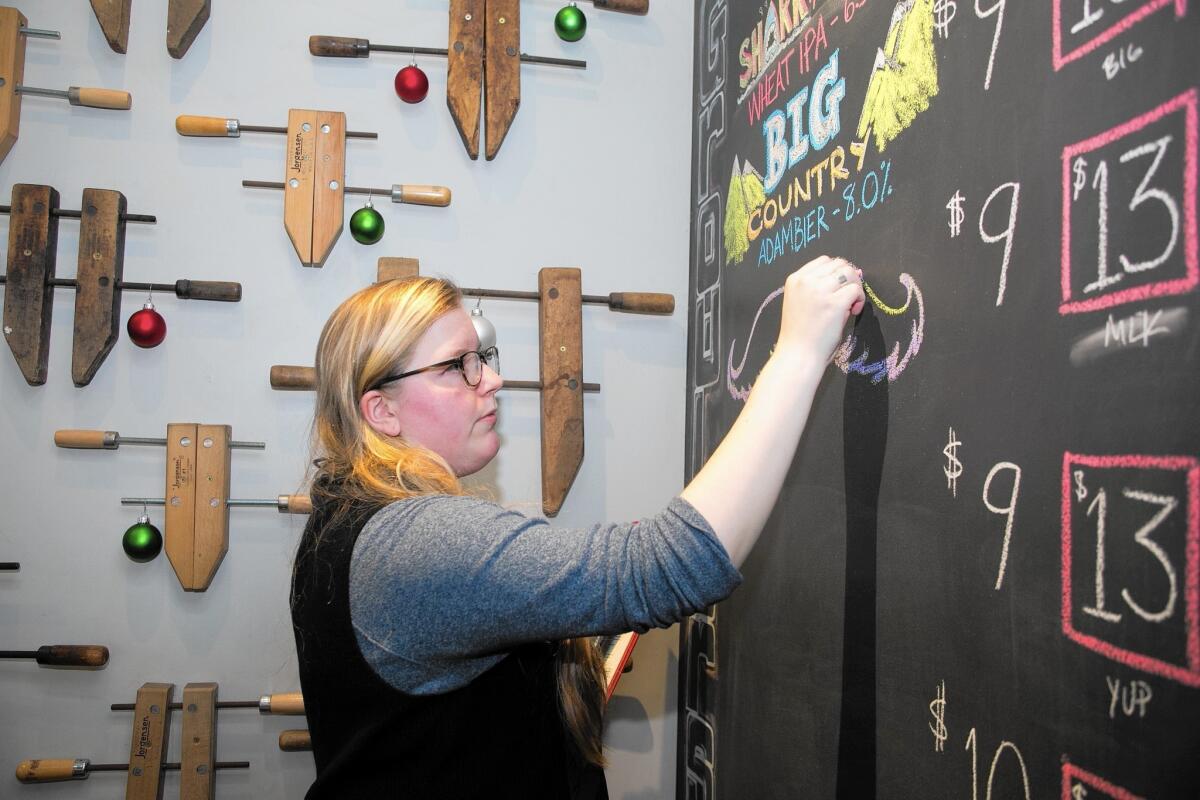

Golub cobbles together a living chauffeuring passengers through the ride-hailing app Lyft, working part-time in the IT department at her old high school and sketching chalkboard art for restaurants and other businesses on a freelance basis. Sometimes one gig leads to another, such as when a conversation with a Lyft passenger got her a job doing illustrations for a children’s book.

“I enjoy the hustle so much more than the grind of full-time work,” said Golub, 24, who lives with a roommate in Chicago’s Gold Coast neighborhood and is on her parents’ health insurance plan, thanks to an Obamacare provision that extended the cut-off age to 26.

Enjoy it or not, more people are hustling.

A growing share of the U.S. workforce relies on alternative work arrangements, which include on-demand gigs through online platforms like Lyft or Uber as well as work through temporary help agencies, freelance assignments and independent contracts.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics plans to conduct a comprehensive survey of these so-called contingent workers next year, its first since 2005, helping policymakers understand the size and makeup of a workforce not covered by many labor protections or privy to the benefits that come with a traditional employer relationship.

In the meantime, private research has shown significant growth in alternative arrangements that at best offer workers flexibility and at worst deprive them of economic security.

Nearly 16% of workers were engaged in alternative work arrangements in 2015, a jump from 10% in 2005, according to research released this year by Harvard economist Lawrence Katz and Princeton economist Alan Krueger.

The share of workers who actually work in the online “gig economy” — through Internet companies, doing app-driven ride hailing or home sharing services, for instance — is much smaller, less than 0.5% of the labor force, Katz and Krueger found.

All of the net employment growth from 2005 to 2015 occurred in alternative work arrangements, the researchers concluded, suggesting there was no net employment growth in traditional jobs.

That research only counted work that was considered someone’s main job. If you include moonlighters who have traditional jobs and hustle on the side, the freelance population this year was estimated at a third of the workforce, or 55 million Americans, an increase of 2 million people since 2014, according to a survey released in October by the nonprofit Freelancers Union and Upwork, an online freelance work marketplace.

“Many people expect that by 2020 to 2025 up to 50% of the workforce will get some income from independent labor,” said Kristin Sharp, executive director of the Shift Commission on Work, Workers and Technology, an initiative of New America, a public policy think tank.

Whether policy will catch up to the labor shifts is a question experts will watch in 2017. A major conversation point has been how to develop portable benefits that give gig economy workers access to retirement plans, unemployment insurance and paid sick leave even as they move from job to job.

“I think we’ll start to see concrete proposals this year,” Sharp said.

The Affordable Care Act, which allows individuals to buy insurance on healthcare exchanges, has been credited with freeing people from the reliance on employers for health insurance. So the law’s fate under President-elect Donald Trump, who has vowed to repeal at least parts of it, could affect people’s willingness to work independently, said Brian Kropp, human resources practice leader at business advisory firm CEB.

“If it is replaced, the gig economy will take a big hit,” Kropp said.

With Trump’s selection of fast-food executive Andy Puzder to be Labor secretary, some worker advocates say there’s greater urgency to implement safeguards for contingent workers. Under President Obama, the Labor Department has been aggressive on issues of worker misclassification — that is, companies classifying workers as independent contractors or using temporary staffing agencies to avoid paying benefits like overtime, unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation.

The National Labor Relations Board, a separate independent agency, under Obama expanded the joint-employer definition that holds parent companies liable for infractions alongside franchisees.

Puzder, chief executive of CKE Restaurants, parent of the Hardees and Carl’s Jr. restaurant chains, is expected to be sympathetic to businesses wanting flexibility in their workforces, “so it places even more importance that social policy makes sure that nonprofits can offer ways for people to choose benefits,” said Sara Horowitz, founder and executive director of Freelancers Union, which provides advocacy and health insurance to its members.

The potential reasons for the recent growth of the gig economy range from necessity, for those who lost their jobs during the Great Recession, to workers’ desire for flexibility and efforts by companies to cut costs.

The rise in platforms such as Airbnb and Uber also have made it easier for independent businesspeople to interact with customers and turn their homes and cars into income streams. But rather than represent the future of work, data suggests online platforms offer handy side gigs when things get tough.

In June, Los Angeles residents earned a monthly average of $960 from labor platforms, and established participants made just less than a quarter of their annual incomes on the platforms, according to JPMorgan Chase.

It said that 50% of online labor platform users in Los Angeles dropped out within 12 months, and that nationwide, turnover was particularly high among employed, higher-income and younger participants, suggesting people opt out as the economy improves and they find other jobs.

“It is a new and easily accessible form of work, but people are treating this as a secondary source of income,” said Fiona Greig, research director for the JPMorgan Chase Institute.

Times staff writer Samantha Masunaga contributed to this report.

ALSO

Here’s what happens on the airplane before you board your flight

Trump economy poses big risk and potential big reward for California

Warehouses promised lots of jobs, but robots are invading the workforce

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.