For ‘Swingin’ Years’ radio host, big bands’ allure endures

Chuck Cecil’s big band radio show, ‘Swingin’ Years,’ has been on the air almost continuously since 1956.

- Share via

C

huck Cecil went to his first big band show in 1939, driving with three high school friends in a Model A Ford to South Gate to see bandleader Jimmie Lunceford at the Trianon Ballroom.

The following year, he was at the opening of the Hollywood Palladium to see Tommy Dorsey and a skinny singer named Frank Sinatra.

Nearly three-quarters of a century later, Cecil is still swinging to the same music: His weekly big band radio show, "Swingin' Years," has been on the air almost continuously since it debuted in 1956.

It began as filler for an empty Saturday morning slot on Hollywood's KFI station and was later syndicated to more than 300 stations nationwide and broadcast internationally, on 240 ships and 170 military bases, by Armed Forces Radio Network. Though the show is now heard only on Long Beach's KKJZ and Long Island's WPPB, it reaches an average of 46,000 listeners a week.

His cheery Midwestern tones larded with corn-pone quips like "Let's split an egg and fry a watermelon," Cecil intersperses big band music with factoids about the songs and firsthand memories of the men and women who recorded them — the Detroit Tigers, for instance, were winning the World Series the day Bing Crosby recorded "Only Forever."

Now almost 91, the host seems a little mystified by the show's longevity — but not by the long-lived popularity of the music.

"It was an emotional time, and a hardship time, but it was a survival time," said the slim, white-haired Cecil, dressed in denim jeans and a chambray shirt that brought out the blue in his eyes. "That's why the music was so treasured. It did lift people's spirits during the Depression and the war."

Cecil was born the day after Christmas 1922 to a rancher who lost hundreds of heads of cattle and 650 acres of good Oklahoma land in the drought that brought on the Dust Bowl and preceded the Great Depression.

When his father couldn't feed his family of six anymore, he loaded them into a truck and drove to California, installing them in an apartment in Hollywood while he began building a house in what is now Sherman Oaks.

At Van Nuys High, he double-dated with local girls Jane Russell and Norma Jean Baker before they became movie stars (and Miss Baker changed her name to Marilyn Monroe). A drama teacher told him he had a good voice for radio.

It was an emotional time, and a hardship time, but it was a survival time."— Chuck Cecil

During World War II, despite a childhood injury that left him with a lifelong limp, Cecil left a note for his mother saying he was going to enlist and might be late for dinner, and went off to join the Navy. He trained to fly Grumman Wildcats, and had just qualified for combat duty when the war ended.

By then, Cecil had already studied broadcasting at Los Angeles City College. Newly out of the service, he landed a job at a new station in Klamath Falls, Ore. The gig included doing a "remote broadcast" of a local performance by a 17-piece big band accompanied by a 16-year-old female vocalist.

Her name was Edna. When she turned 17, Cecil married her.

That was 1947. "Their" song was Perry Como's "They Say It's Wonderful."

When Cecil was hired by KFI in 1952, the big band years were already over. "Swingin' Years" was an exercise in nostalgia, right from its debut four years later.

"Big band music was in decline," Cecil said. "The big bands themselves were fading in popularity. It was vintage music."

But the show was a hit and became a weekly feature.

Chuck and Edna set up house in the San Fernando Valley, when it was still mostly orange groves, and raised four children. Cecil, by now a local celebrity, was made honorary mayor of Woodland Hills and asked to ride in open cars in local parades.

The show grew in popularity. Disneyland hired Cecil to do a series of "Swingin' Years" shows in 1961. Ronald Reagan did a "Swingin' Years" TV special in 1962. Cecil even hosted "Swingin' Years" cruises, sailing the Caribbean with bandleader Freddy Martin.

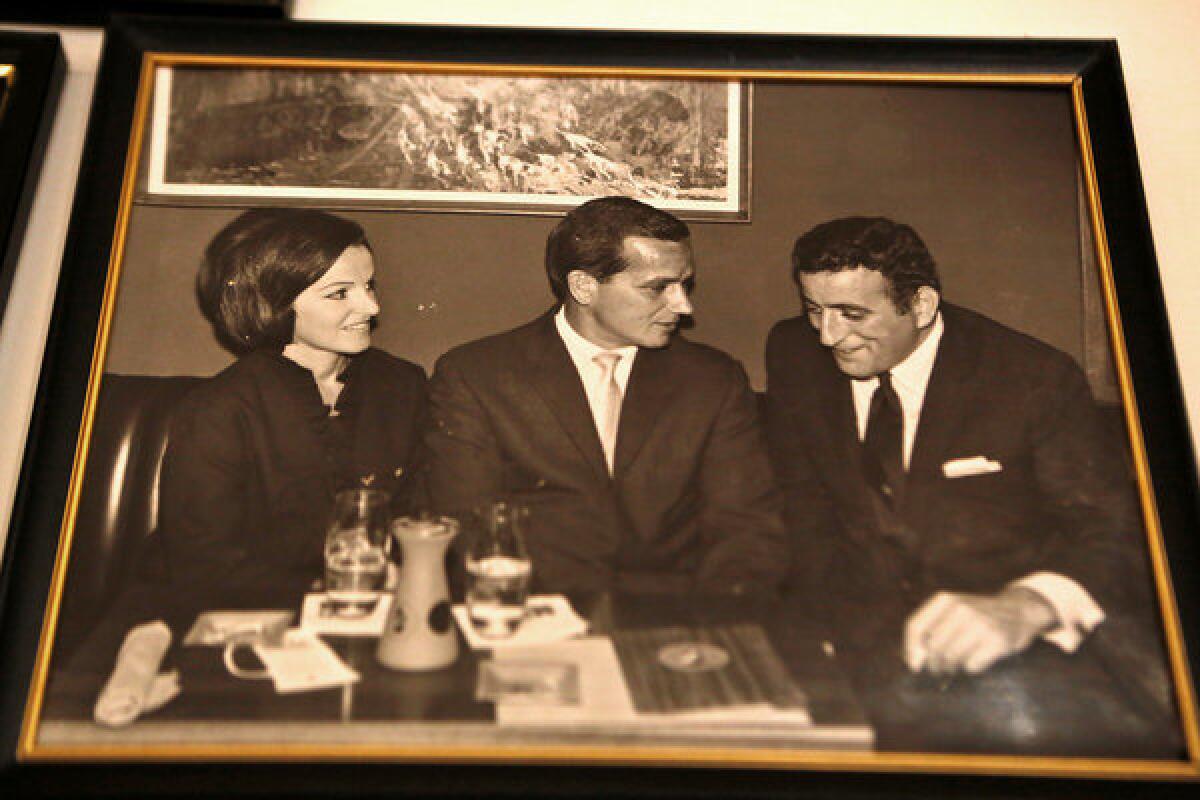

A photo from a different era shows Chuck Cecil, center, with his wife, Edna, and crooner Tony Bennett, who has called Cecil "a great jazz historian." More photos

Cecil hung out with Harry James, lunched with Artie Shaw and Bing Crosby, and interviewed Peggy Lee in her boudoir. (He sat on the bed while the singer reclined.) Cecil recorded and archived the interviews, using them to introduce his listeners to the men and women behind the music.

Bandleader Shaw, Cecil remembers, invited him to his Newbury Park house and then insisted on doing the interview while driving to lunch. "It was the most terrifying drive of my life," Cecil said. "He was a wild driver."

The opportunity to interview Crosby arrived suddenly, when a record producer friend said, "I can get you in to see him, but you have to come while he's eating lunch." Cecil asked questions while Der Bingle ate a burger.

"This music is the voice of America, and he has documented it," said veteran deejay Bubba Jackson, who hosts an evening KJazz blues show. "Thanks to Chuck Cecil, that music will never disappear. He is one of the great historians of American culture."

Crooner Tony Bennett, who at 87 is three years younger than Cecil, called the radio host "a great jazz historian."

"I want to thank him for keeping the music alive," he said, "and for playing my records all these years!"

Today, the Cecils are spry and active, and walk a brisk three miles a day near their tidy Spanish-style home on a quiet Ventura street, where they moved 11 years ago.

"That's one of the reasons we moved to Ventura — because we can walk to the market, to the shops, to the doctor," Cecil said. "We can walk everywhere but the cemetery."

On Sunday, there's no walk. Instead, the Cecils attend church in the morning and go dancing in the afternoon.

Cecil confessed he's no hoofer, though he and Edna did sign up for swing dance lessons a few years back.

"Radio announcers are like musicians," he said. "They generally can't dance."

Nevertheless, their Sunday ritual includes a circuit of big band-themed events at clubs in Ventura, Oxnard, Canoga Park and Simi Valley.

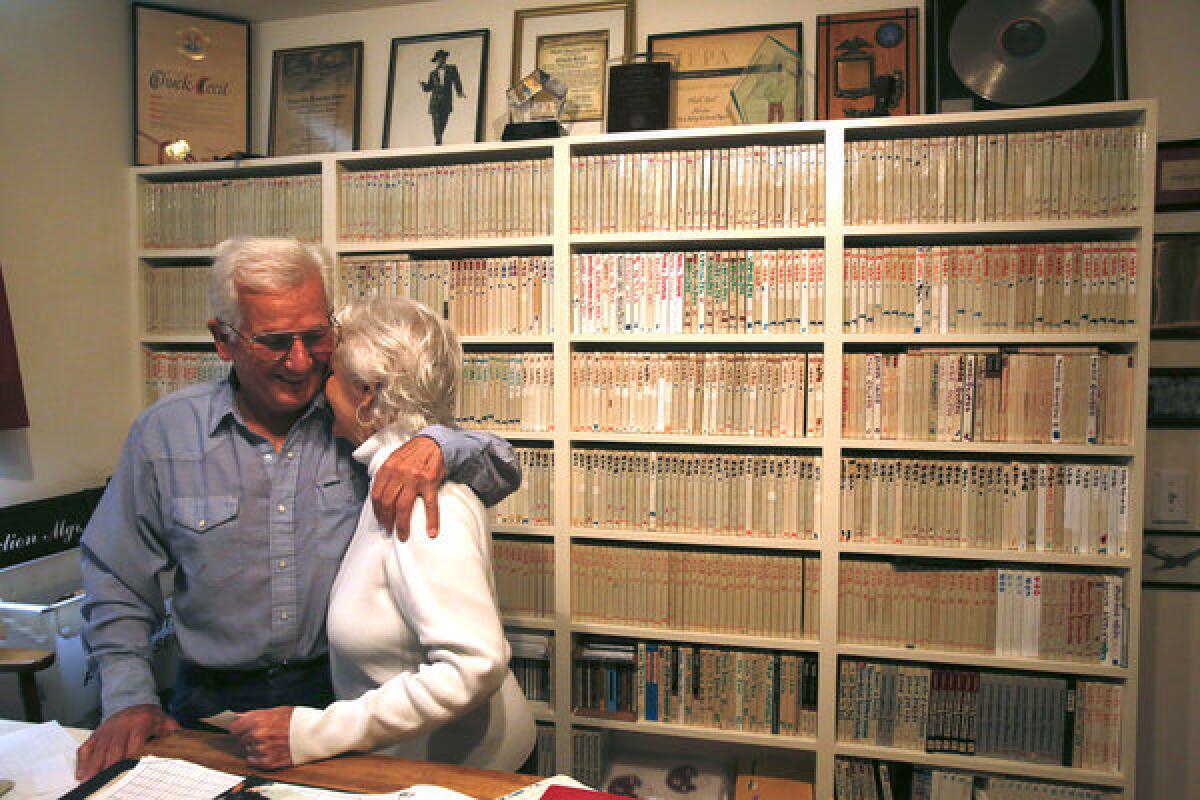

Each week, Cecil and his wife assemble "Swingin' Years" manually, without the aid of computers, for the Saturday and Sunday morning broadcasts. The recording studio is a back room of their home filled with casual photographs of the radio man sitting with jazz giants such as Woody Herman, Count Basie, Lionel Hampton and Bennett.

Working from a massive library of more than 30,000 78-, 45- and 33-rpm records, and his own personal library of interviews with 356 band leaders, singers and sidemen, Cecil mixes dance tunes, sentimental ballads, jazzy jumpers and novelty records. Often you can hear the sizzle of the needle on the platter.

Cecil said he sometimes tires of the 15 to 20 hours required to produce each week's "Swingin' Years" broadcasts. "I've done more than 20,000 hours of programming," he said. "Maybe that number has got my attention, but I've lost a little of my zip for the show."

Despite that, Cecil was planning to do a new "Swingin' Years" series on bandleaders and their theme songs — Glenn Miller's "Moonlight Serenade," Duke Ellington's "Take the 'A' Train" — and another on the lesser-known sidemen who worked for the famous bandleaders.

After working in his recording studio, deejay Chuck Cecil gets a hug from Edna, his wife of 66 years. More photos

Almost none of the musicians Cecil admired or befriended are still alive.

"When you get past 90, people really start corking off," said Edna Cecil, who celebrates back-to-back birthdays with her husband, turning 84 on Christmas Day. "But not us!"

The Cecils' daughter Sherri recently returned to Ventura, moving in with her parents and bringing modern technology with her: the Internet.

As a result, Cecil was able to hear his own show for the first time since he moved to Ventura, which doesn't have a radio station that broadcasts "Swingin' Years."

A couple of Saturdays back, he and his wife tuned in to a live stream from WPPB in Long Island.

"I lit two candles and we sat there with sandwiches and wine and the music — for four whole hours," Edna Cecil said. "It was heaven."

She said her husband fails to appreciate his own contribution to the American music scene.

"He doesn't realize how important he has been," she said. "Many musicians tell him that — 'You kept the music alive.' But he doesn't have a clue."

Follow Charles Fleming (@misterfleming) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

Boyle Heights tailor is the master of mariachi suits

Betting big on a citadel for the Afghan elite

No one wants to return to the way things were in the past. I believe in a different future."

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.