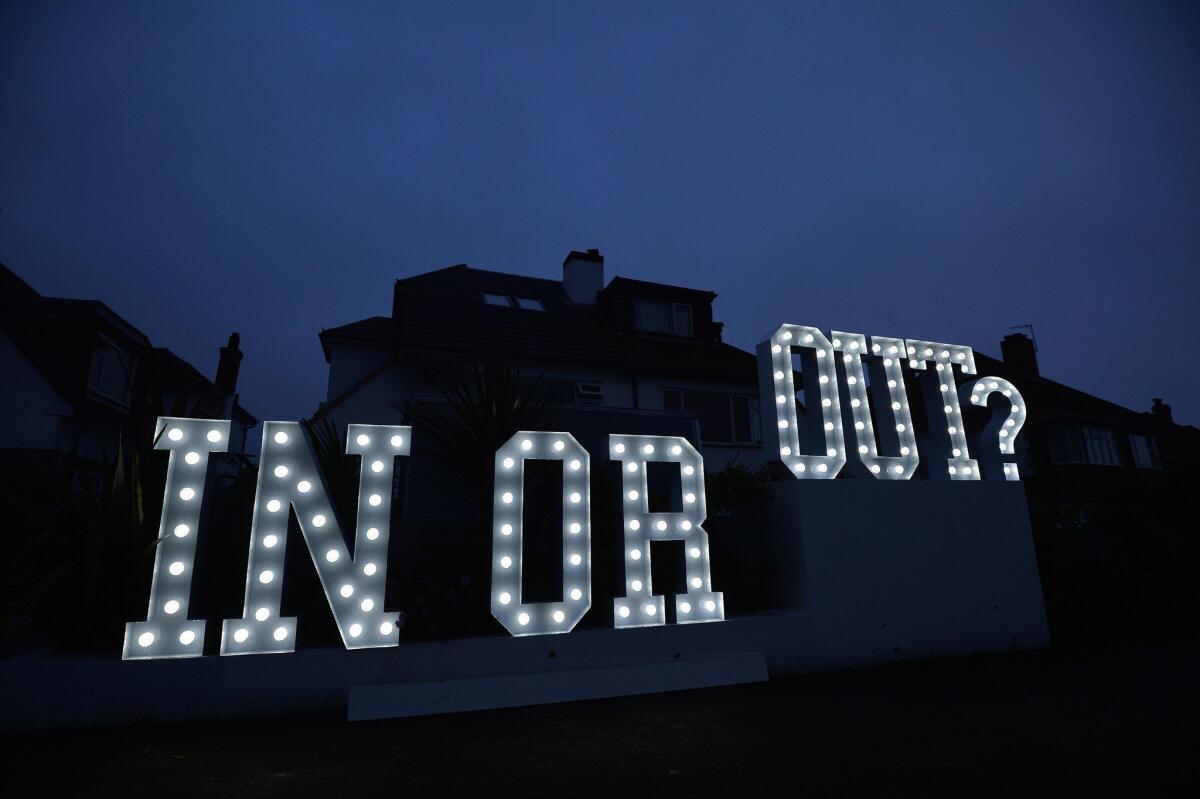

Will the ‘Brexit’ mark the end of the age of globalization?

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — For decades, financial and political leaders have preached the inevitability of globalization, promising nations that by sacrificing some of their sovereignty and dropping national barriers they could reap far greater rewards through economic integration and cooperation. And that turned out to be largely true.

But Britain’s surprise vote to leave the European Union signals a new era for the post-World War II globalization drive, exposing deep populist anger and leaving open the question of how best to rein in an increasingly connected and interdependent world economy.

The vote was perhaps the biggest public referendum to date on globalization, and it yielded a far different outcome than in 2014, when Scots voted to stay part of Britain.

Now Britain and other Western democracies are likely to face growing pressure to put the brakes on open trade and immigration policies that have been hallmarks of world growth.

“The age of globalization has certainly ended,” said Fredrik Erixon, director of the European Center for International Political Economy, an independent think tank in Brussels.

Few are predicting a scenario in which major borders are closed and protectionism rules the day. But the sentiments underlying the British public’s rebellion are broadly shared by many others in the EU as well as the United States.

Policymakers and investors are particularly worried that Britain’s move will be a catalyst for a reenergized effort by Scots -- who overwhelmingly favored remaining in the EU -- to break away fromBritain. It may also encourage other secession movements in the EU, which could fundamentally alter the political and economic structure that has been in place for decades.

“With one fell swoop, the world order has been turned upside down overnight, and where the chaos stops no one knows,” said Chris Rupkey, chief financial economist for Mitsubishi UFG Financial Group.

The backlash stems from a growing realization that the biggest winners of globalization have been international corporations, wealthy families, skilled and educated workers and those with easy access to capital. Older, working-class families in many Western nations have instead struggled with stagnant wages, job losses and staggering debt. Income inequality has grown worse in many of the same countries that have embraced globalization.

A U.K. departure is going to make the entire EU inward-looking, more defensive on globalization and less confident about making it on the back of the world.

— Fredrik Erixon, director of the European Center for International Political Economy

At the same time, forces that once propelled globalization -- advanced technologies, reduction of barriers and the rise of China and other developing economies -- have diminished. World trade and economic growth have also slowed in recent years.

With the so-called Brexit vote, the European Union, itself arguably the most ambitious post-World War II experiment in globalization, appears at risk of unraveling.

“In the postwar period, with the shadow of world wars and the shadow of the USSR no longer over Europe, countries are increasingly ready to go back to nationalism,” a European diplomat told reporters in Washington on Friday, speaking anonymously to comment on other countries’ politics.

In the U.S., the antiglobalization tide has led to public opposition to sweeping trade deals, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement and the proposed 12-nation trade pact known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, the presumptive presidential nominees, oppose.

President Obama, speaking to entrepreneurs from around the world at a Global Entrepreneurship Summit on the Stanford University campus, acknowledged Friday that Britain’s vote “speaks to the ongoing changes and challenges that are raised by globalization.”

Obama called upon business leaders to work harder to make the benefits of globalization more accessible to a greater number of people.

“The world has shrunk,’’ he said. “It is interconnected.... It promises to bring extraordinary benefits. But it also has challenges. And it also evokes concerns and fears.”

At the core of the “Leave” campaign in Britain was the desire to curtail immigration and reclaim full sovereignty in Parliament.

“Both of those are incompatible with a world that is increasingly globalized,” said Erixon, the think tank director. He added that “a U.K. departure is going to make the entire EU inward-looking, more defensive on globalization and less confident about making it on the back of the world.”

The EU was born out of the ashes of two world wars that had divided the continent, and the single market and political union had grown to 28 members as European leaders saw stronger economic and social integration as a way to compete in a world increasingly orbiting around the United States and China, the two largest economies.

It’s surprising that one of the most sophisticated countries would fall for this.

— Robert Shapiro, former economic advisor to President Clinton

But anti-EU feelings have deepened in the wake of its inability to respond effectively to the global downturn and the Eurozone crisis, as well as to manage the heavy migration from Eastern Europe and, more recently, waves of refugees from the Middle East.

What’s more, as in the U.S., the economic recovery has left out large segments of the population in Britain and elsewhere in the EU. And they have become increasingly frustrated at what they see as a lack of government actions to address their needs.

“The really, really surprising part of the Brexit referendum and rebellion against globalization is that it’s held up by the group of baby boomers that have benefited enormously from open societies,” Erixon said. “Now they’re rebelling against their own economic history.”

In Europe and the U.S., complaints have been particularly loud from older and less-educated citizens who have struggled with job loss or income stagnation. Many of their livelihoods have been undercut by automation and cheaper foreign labor -- two prominent features of globalization -- even as corporations and wealthy individuals have gotten richer.

“This vote [in Britain] was mobilized around issues of nationalism defined in ethnic terms,” said Robert Shapiro, chairman of consulting firm Sonecon and a former economic advisor to President Clinton. “It’s surprising that one of the most sophisticated countries would fall for this,” he said. “That tells us about the fundamental failure of the EU.”

The pushback against globalization also raises a new question: What’s the alternative? So far, there’s much more agreement on the problems globalization has created than on any solution or response.

The direct and immediate economic pain will be felt hardest in Britain. The nation’s economy had outperformed most others in Western Europe in recent years but is now likely to tip into recession in coming months.

The world has long regarded London as the financial capital of Europe, but one of the things that gave it that imprimatur was the city’s cosmopolitan culture and free flow of workers. Now it may end up a casualty of the globalization backlash.

“It’s clear that there’s a lot of dissatisfaction out there,” said Clyde Prestowitz, president of the Economic Strategy Institute and a former top trade negotiator in the Reagan administration. The problem has been building for years, he said, but the political and business elite in urban centers such as London, New York and Washington have tended to do fine whether the economy is up or down.

“What they have ignored,” he added, “is that for much of the population, globalization hasn’t been such a great thing.”

ALSO

Op-Ed: The isolationist catastrophe of ‘Brexit’

Are California companies vulnerable to ‘Brexit’ turmoil?

The British establishment didn’t think ‘Brexit’ could win, but it did. Here’s why.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.