Advertisers are in the hot seat as activists both for and against Trump call for boycotts

Activist groups have long employed boycotts to pressure major media outlets to conform to their political agendas, but what distinguishes the campaigns of 2017 is the speed at which they propagate across social media. (June 14, 2017) (Sign up for ou

- Share via

It has come to feel like a weekly, even daily occurrence. Following a media firestorm, usually related in some way to President Trump, advertisers face calls to sever ties with the company at the center of the outrage du jour, or else suffer a publicity crisis.

In the days leading up to Megyn Kelly’s interview with Alex Jones, activists are demanding advertisers dump the NBC broadcast, claiming the show is giving a platform to the pro-Trump host of Infowars. The Web-based video and radio network has been criticized by many as a promoter of conspiracy theories, including repeatedly suggesting the shooting that killed 26 people at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., in 2012 was a hoax.

Earlier this week, Bank of America and Delta Air Lines dropped their sponsorships of the Public Theater’s staging of Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar” in New York, following an online furor over a scene in which the title character, dressed to resemble Trump, is stabbed to death.

Last month, USAA, the insurance and consumer finance company, pulled its commercials from “Hannity” on Fox News, only to reverse its decision days later following intense blowback from its core customer base of military families and veterans, many of whom also are loyal viewers of pro-Trump commentator Sean Hannity.

Advertisers find themselves in an increasingly precarious position as activists pressure them to pull ads from conservative media outlets that are sympathetic to the Trump administration, particularly Breitbart News and Fox News.

That list is expanding, with NBC being the latest target as JP Morgan Chase pulled back its local TV advertising on Kelly’s show and other NBC News programming until after the Jones segment airs Sunday night.

In a hyperpolarized media landscape, companies that previously saw themselves as apolitical now find that their ads and promotions generate instant political heat based simply on where they appear.

“There is no easy decision here. The country is divided right down the middle,” said Chris Riccobono, founder of Untuckit, the New York-based men’s clothing retailer.

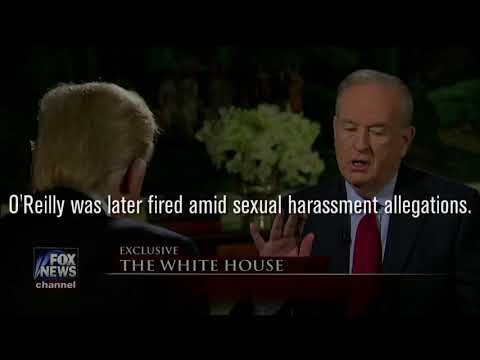

The company was one of many to pull its commercials from Fox News’ “The O’Reilly Factor” following the sexual harassment scandal surrounding host Bill O’Reilly. But it has resisted pressure to remove its ads from “Hannity.”

“We advertise across the full range of the political spectrum because, frankly, our customers fall along the full range of the political spectrum,” Riccobono said. “We are ardent supporters of free speech.”

A representative for Viking Cruises, which runs commercials on “Hannity,” added: “The objective of Viking’s television advertising is to reach our customers on the channels that they are watching. … It does not mean that we advocate for any of the content portrayed on these news networks.”

Advertiser boycott campaigns aren’t new. Activist groups have long employed the tactic to pressure major media outlets to conform to their political agendas. “I’ve had to deal with this since the day I walked in the door,” said Lisa Herdman, a senior vice president at RPA, a Santa Monica-based advertising and marketing agency.

But what distinguishes the campaigns of recent months is the speed at which they propagate across Twitter and Facebook, fueled by partisan passions about Trump.

Some advertisers said they are in a reactive position because they rely on third-party ad exchange networks to place their content and aren’t always aware where their ads appear.

The legal referral site Avvo told exchanges to remove its online ads from Breitbart in November after company leaders were alerted by activists, including the anonymous social media group Sleeping Giants, which has aggressively targeted the conservative news site.

“I’m sure there are people who visit Breitbart who could benefit from services we provide,” said Josh King, chief legal officer at Avvo. “But it’s a site we’re not comfortable our brand being associated with.”

He said Avvo concluded that Breitbart promotes racist and sexist views and traffics in fake news, but he didn’t cite specific articles. Breitbart, which declined to comment, has previously refused such claims. The site has published incendiary articles with provocative headlines like a recent series on terrorist attacks titled “Ramadan Rage” and a story on the European refugee crisis titled “Political Correctness Protects Muslim Rape Culture.”

Stephen Bannon, Breitbart’s former executive chairman, serves as chief strategist to Trump.

Avvo, which is based in Seattle, noted that the political beliefs of its employees played a role in its decision. “Our employees are pretty progressive,” King said.

Advertisers often will take cues from the political leanings of their own staff when weighing whether to participate in a boycott, said Brayden King, a professor at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University.

“These decisions are made by real people, with ideological points of view,” he said. “Companies that have more liberal executives tend to support more liberal causes.”

There is also a brand safety motivation, he said. “When you see advertisers pull their ads from shows, it reflects their need to avoid controversies. They don’t want to be associated with a political figure or personality who is extreme or contentious at the moment.”

USAA, which declined to be interviewed, said in a statement that “the lines between news and editorial are increasingly blurred.” The San Antonio company said it is reviewing its advertising policy.

The company is one of many to be pressured by Media Matters for America, a liberal activist group that has long targeted Fox News. The nonprofit organization, which was a key player in the firing of O’Reilly and the effort to unseat Hannity, noted that advertiser boycott campaigns have devolved into wars of attrition between opposing sides.

“At some point, you make it so that no one can sponsor anything,” said Angelo Carusone, president of Media Matters. “A lot of campaigns are lose-lose for everyone.”

But he said contacting advertisers still can be an effective tool for activists when other means have been exhausted, such as putting pressure on the parent company of a media outlet.

Companies that have more liberal executives tend to support more liberal causes.

— Brayden King, professor at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University

Advertiser boycotts can have significant financial impact.

The Gateway Pundit, a popular right-wing news site, said that ad exchanges began dropping it this year following pressure from activist groups. The site, which critics have blasted as racist and a purveyor of fake news, relies almost entirely on online ad revenue for income, according to founder Jim Hoft.

He said the exchanges described the site as “undesirable.” “I may have a different view on immigration, but that doesn’t make me a racist,” he said.

Breitbart has seen exchanges including AppNexus cut ties, but the financial impact on the privately held, L.A.-based outlet remains unclear. A recent study from MediaRadar, a New York ad sales tracker, said Breitbart has seen a nearly 90% drop in ads in recent months. But the firm said the study doesn’t count sponsored content that also generates revenue for Breitbart.

Advertising platforms like Taboola currently partner with Breitbart to display sponsored content on its site. Taboola didn’t respond to a request for comment, but CEO Adam Singolda wrote in a company blog post shortly after the presidential election that “it is important to accept and include all opinions on the web.”

Conservative activists have just started getting in the ad boycott game, with groups like the Media Equality Project calling for advertisers to yank their commercials from CNN and MSNBC. But their resources are small compared to groups on the left.

They were part of a growing army of online conservative agitators who recently contacted CNN’s advertisers in an effort to target Kathy Griffin and Reza Aslan, both of whom were subsequently fired by the cable news network.

“You can organize these things quickly and efficiently now,” said Brian Maloney, a co-founder of Media Equality. “Companies freak out pretty quickly.”

ALSO

Megyn Kelly’s interview with conspiracy theorist Alex Jones becomes a headache for NBC News

NBC has high hopes for Megyn Kelly. But can she compete with ’60 Minutes’?

Review: Megyn Kelly gets outmaneuvered by Vladimir Putin on her NBC premiere ‘Sunday Night’

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.