Can a company do well by being nice? Comcast (and others) will try

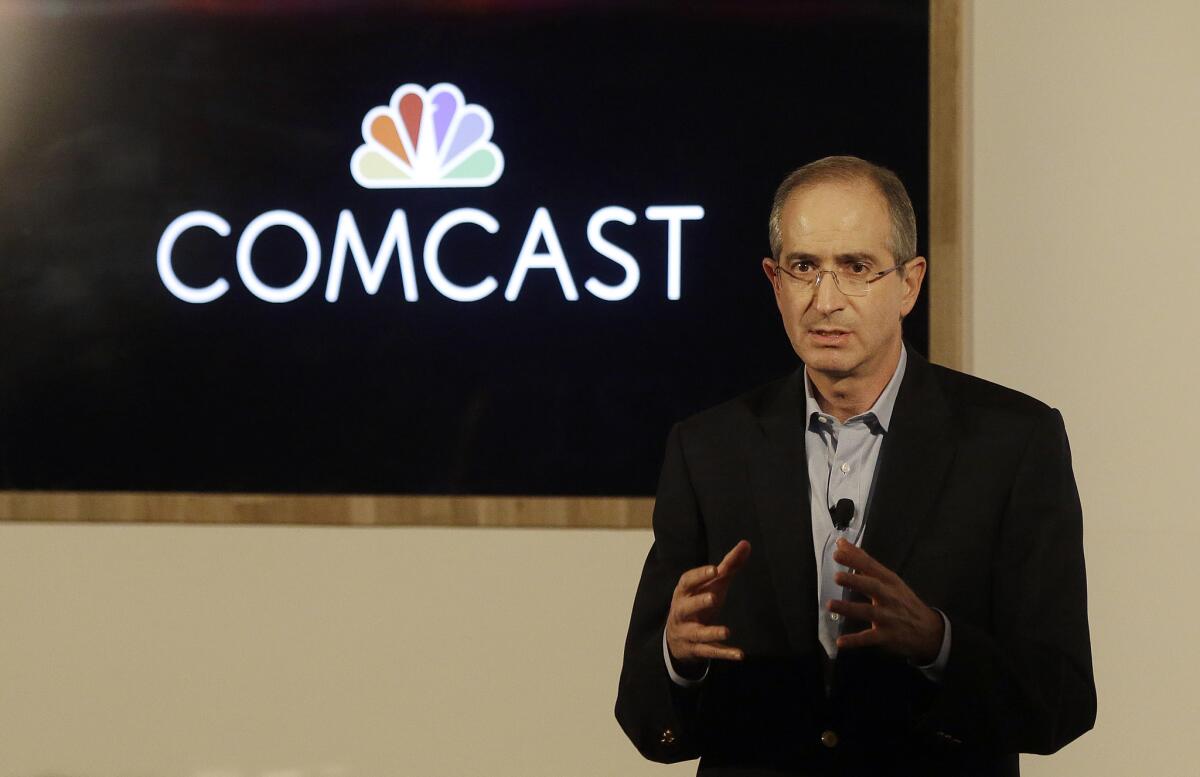

Comcast CEO

- Share via

Few corporations have received a more punishing lesson in the cost of being nasty than Comcast. In April, the giant cable operator was forced to call off its $45-billion acquisition of Time Warner Cable, at least in part because of the overt hostility of customers and regulators caused by its long record of broken commitments and awful service.

The company says it got the message. Days after its spanking, Comcast announced that it would “reinvent” the customer and employee experience by hiring 5,500 new customer service reps and technicians, provide them with new training, and give customers firm commitments on service calls.

That’s a big turnaround for a company known for a customer service record that put the “noxious” in “obnoxious.” But CEO Brian Roberts labeled “unacceptable some of the individual instances that have been well-documented...And so it was a rallying cry, I think, inside the company, that we are going to top-to-bottom rethink the way we do business.”

The jury is out, and as we’ll see, there are reasons to doubt Roberts’ pledge. But it may reflect a revived recognition among business leaders that a reputation for poor treatment of customers, employees and local communities can be costly, even when one offers alluringly low prices to compensate for the snarling.

The “niceness” strategy is surely a factor in wage initiatives recently announced by Wal-Mart, McDonald’s and other large employers of low-wage workers; it can scarcely profit a consumer-oriented company to be seen as a drain on public resources by turning its workers into wards of government welfare and healthcare programs.

The good corporate citizen movement even has a public face--”B Corporation certification,” issued by a nonprofit called B Lab to companies that “meet rigorous standards of social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency.”

For some businesses, the B Corporation label is money in the bank: The online crafts retailer Etsy warned would-be investors in its recent initial public offering that “our reputation could be harmed if we lose our status as a Certified B Corporation...if that change in status were to create a perception that we are more focused on financial performance and are no longer as committed to the values shared by Certified B Corporations.”

The most interesting example of a company shedding its noisome reputation may be Ryanair, a short-haul Ireland-based airline that long held the prize as “the world’s most hated airline.” Americans may remember Ryanair as the carrier that once pondered charging passengers for going to the lavatory and allowing passengers to fly as straphangers. These notions may have merely reflected the warped sense of humor of CEO Michael O’Leary, but in one notorious documented episode, the company charged a distraught passenger a $250 change fee when he tried to reschedule a flight moments after learning his entire family had died in a house fire.

In 2013, O’Leary launched a new strategy aimed at trying not to “unnecessarily piss people off.” No more would gate staff charge passengers bag fees for carry-ons that were only a millimeter oversized, inflexible fare rules were loosened and so on. Traffic has risen by as much as 25% year-over-year. But the new attitude comes with its own costs: By some measures, Ryanair’s fares have been rising, too.

Few companies illustrate the costs and benefits of superior customer service like Amazon.com. Proactive and indulgent customer policies have fueled Amazon’s expansion into the retailing giant it is; they’ve also consistently sapped its bottom line. The company is world renowned for making almost no money even as it dominates the online retailing space; in the year ended Dec. 31, it lost $241 million on sales of $89 billion. But there are scant signs that investors are growing weary of the losses.

That brings us back to Comcast. Like other cable and Internet service companies, which all tend to rank low in customer satisfaction, Comcast problems are self-inflicted artifacts of its position as a monopoly provider. Why bother keeping customers happy or being price-competitive when you know they have nowhere else to go for cable service and almost always nowhere else to go for broadband Internet?

Still, that scarcely explains the lengths to which Comcast has gone to tick off regulators and consumers. Its record of flouting its own commitments to government agencies was stunning, as we chronicled when it announced the Time Warner Cable deal. Its customer service produced one of the true landmarks of the Internet age, this recording of a customer’s nearly 20-minute effort to get a Comcast rep to cancel his account.

Whether Comcast really can remake itself is unclear. The change requires more than a bigger customer-service staff; it requires an entirely new approach at the top. The evidence is that Comcast customer reps aren’t bad people; they’re just responding to pressure from their bosses to sell, sell, sell. Adrianne Jeffries of the Verge, who interviewed some 150 Comcast employees for a series on how the company does business, pinpointed this melding of functions as the core of the problem.

“You call Comcast because you have a problem, and you end up with a service representative who has to meet a quota for a certain number of sales,” she reported last year. “They’re thinking more about what to sell you than how to fix your problem.”

Comcast’s business strategy was based on aggressive territorial expansion and multi-million-dollar lobbying efforts in Washington, not on creating and pleasing customers. It was an upside-down business model, but it worked--until it stopped working at the end of April. Whether Brian Roberts and his team really have taken the message to heart won’t be known for months, or years.

Keep up to date with the Economy Hub. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email [email protected].

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.