Column: No, California’s drought isn’t over. Here’s why easing the drought rules would be a big mistake

- Share via

On March 23, the San Juan Water District, which serves upper-crust residential estates in the Sacramento area, declared that the drought is over.

After months of El Niño rainfall, Folsom Lake, the district's chief water source, had become so full that excess water was being released over Folsom Dam. "That was a very visible signal," says Lisa Brown, customer service manager for the district. Customers, some of whom own spreads as large as 10 acres, "wanted to know why they were still being held to drought restrictions." So the district board lifted them, replacing a 33% mandatory conservation cutback with a 10% voluntary cut and eliminating a 10% drought surcharge on water rates, effective April 1.

Droughts are really a matter of signals. When it has rained a lot, people get comfortable.

— Jeanine Jones, deputy drought manager, California DWR

The abundance of water, says Assistant General Manager Keith Durkin, made it "very difficult to defend a continued 33% reduction in use."

Across Northern and Central California, brimming reservoirs and a recovering mountain snowpack are prompting water users to pressure Gov. Jerry Brown and the State Water Resources Control Board to ratchet back restrictions that have made California a national leader in conservation.

The Placer County Water Agency on March 18 asked state authorities to rescind emergency drought regulations on the grounds that its supply is "robust enough to meet demand" from its customers through 2017. The Nevada Irrigation District, east of Marysville, cited "well above average precipitation, full reservoirs and a mountain snowpack" in rescinding its own drought declaration and calling on the state to ease its restrictions.

Districts such as San Juan have taken matters into their own hands by unilaterally removing the most stringent regulations on their own customers. San Juan says its customers met their conservation obligation by reducing usage by 34% from June through February. Not all the protesting districts managed that; the Georgetown Divide Public Utility District in El Dorado County, which last month lifted a drought-inspired moratorium on new water connections, acknowledges that it was upbraided by the state board in January for failing to meet its goal.

The Water Resources Board is looking for ways to ease pressure on water-rich districts without giving them a free hand. It has scheduled to consider relaxing some restrictions at a meeting in May, following a workshop at which those districts will be asked to make the case for more flexibility. "In the eyes of Placer County and San Juan the job is over," says George Kostyrko, a spokesman for the board. But water conservation "isn't a regional or a siloed issue," he says. "It's a statewide issue."

Policymakers are getting the uneasy feeling that public impressions of newfound abundance could undo much of the progress of the last few years. "Droughts are really a matter of signals," Jeanine Jones, deputy drought manager for the California Department of Water Resources, told me. "When it has rained a lot, people get comfortable."

That would be a mistake. Experts reckon that even if 2016 represents a break from the record dry conditions of the last four years, the damage done by the drought to the state's water supply will be lasting. Long-term reserves in groundwater have been drained to the point that years, even decades, of wet weather would be required to replenish them. "We've depleted our savings account in reserves and groundwater storage," Jones says.

A more likely scenario for the future is a change in climatic conditions requiring a permanent change in water usage habits. "In the water community, people talk about a new normal, with dry conditions becoming more frequent and more lasting," says Matt Heberger, senior research associate at the Pacific Institute, an environmental think tank in Oakland.

These conditions create a quandary for policymakers, who must tread a fine line between enforcing restrictions that people may feel are no longer necessary while guiding residents, growers and businesses toward enduring changes in usage patterns. "Messaging is important," says Ellen Hanak, a water expert at the Public Policy Institute of California. "It doesn't make sense to tell people conditions are terrible when they're not, but it makes sense to tell them that the precipitation we've gotten hasn't put us in a safe spot."

The habits born in the last few years, if they take root, could produce lasting gains in water sufficiency for the future. The emergency atmosphere of the last couple of years has a lot to do with that: In the same sense that $3-a-gallon gas starts turning people off gas-guzzling SUVs, the best weapon against water shortages in the future is a sensation of crisis today.

Since January 2014, when Gov. Brown declared a drought emergency, Californians have met the challenge. They've replaced tens of millions of square feet of turf with drought-tolerant landscaping (coaxed by hundreds of millions of dollars in utility rebates) and installed water-thrifty indoor fixtures. The results are remarkable: Statewide average residential consumption of 61 gallons a day in January was nearly 15% below the same month a year earlier. Last summer's usage was more than 23% lower than a year earlier.

Indications abound that the regional drought is far from over. The water level of Lake Mead, the reservoir behind Hoover Dam that stores Southern California's Colorado River supply, stood last week at 1,081.32 feet above sea level — a recovery of about 6 feet since it reached a recent low point in June. But that's still the lake's lowest level in any March since 1937, when it was still filling for the first time. Mead is currently at about 39% of capacity.

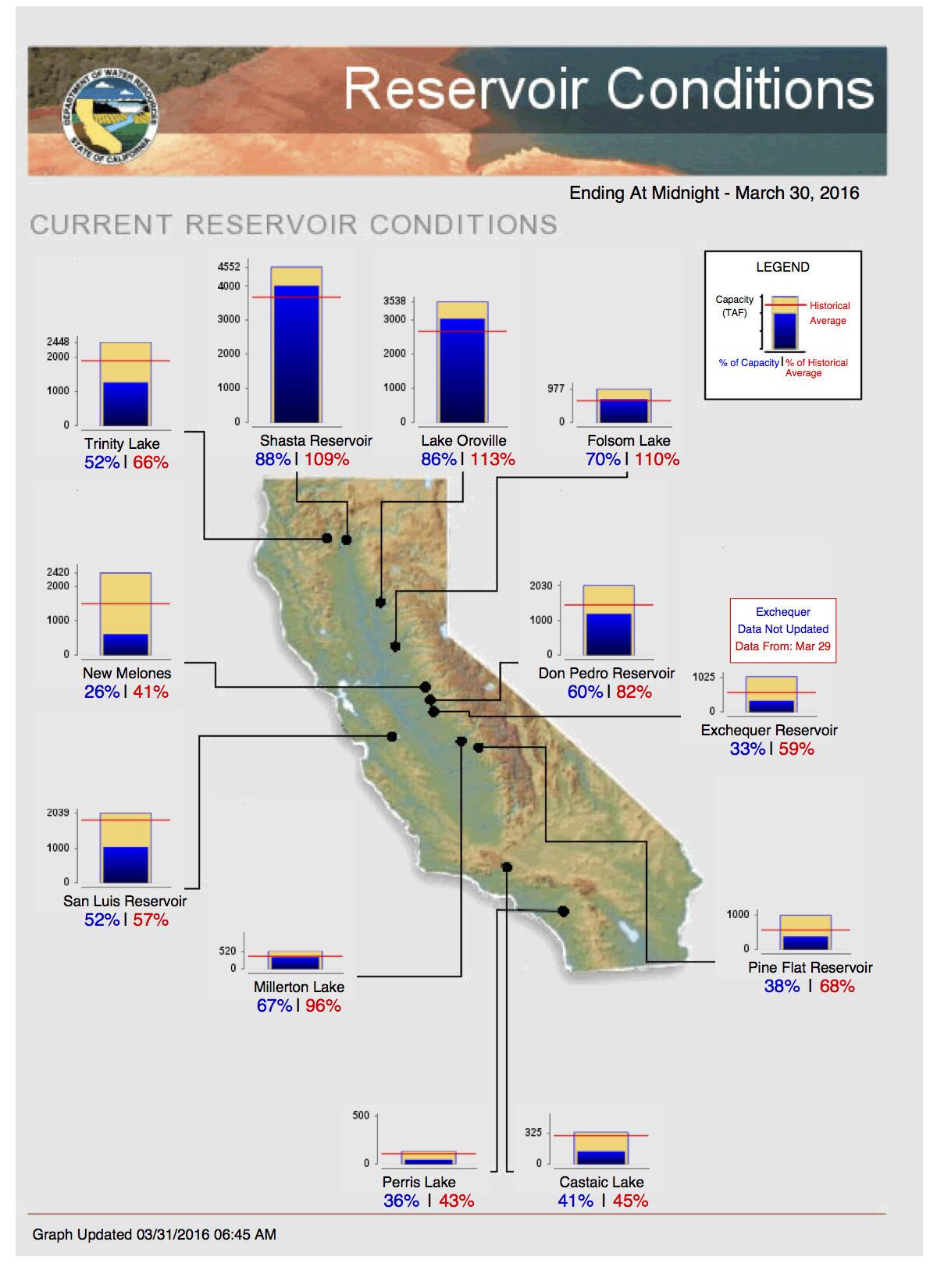

Although three major Northern California reservoirs — Shasta, Lake Oroville and Folsom Lake — are currently above their average historical levels, they're the exceptions, according to the Department of Water Resources.

Reservoirs in Central and Southern California remain well below their averages, with Don Pedro Reservoir in the Sierra foothills at 82% of its average and 60% of capacity, and Perris Lake in Riverside County at 43% of its average and 36% of capacity. While the snowpack is calculated at 87% of normal overall, its depth varies widely across the state — rising over recent months to roughly 100% of the average in the far north of the state, but reaching only about 75% of the average toward the south. The U.S. Drought Monitor still shows much of Southern and Central California to be facing long-term "exceptional drought."

The problem with giving some parts of the state a pass on water rules while maintaining them elsewhere is that California's water supply system binds north and south together. The long-term water crisis can only be solved as a statewide effort.

The state has begun to make changes that may well be lasting. "There will be a different-looking outdoor space 10 or 20 years from now than there was 10 or 20 years ago," Hanak says. But the mind-set producing those changes could be fragile. The message needs to be that "the fact that we're easing up doesn't mean we're out of drought mode."

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Return to Michael Hiltzik's blog.

ALSO

223 drought maps show just how thirsty California has become

Sierra snowpack shows improvement, but not enough to declare California's drought over

Police escorts, curfews and long lines: What it takes to get water in west India