‘On the Road’ toward mortality: A critic ponders Jack Kerouac

- Share via

Time is a key element in Jack Kerouac’s novel “On the Road.” “We know time,” the protagonist Dean Moriarty (based on Kerouac’s friend Neal Cassady) mutters throughout the book, an invocation and a prayer.

That’s important for a couple of reasons: It signals the novel’s hunger for new experience, for a way out of the conformist pieties of post-World War II America, and also Kerouac’s desire to stare down the mortality that he feared. In some sense, this is the key to all his writing, the idea that by mythologizing his life and that of his friends he was somehow placing them all outside of time.

Time, however, catches up with everything, including “On the Road.” The book was published in 1957, and everyone in it is now dead. This raises the question of how we are to read it, as a historical document or as a vibrant piece of literature in its own right.

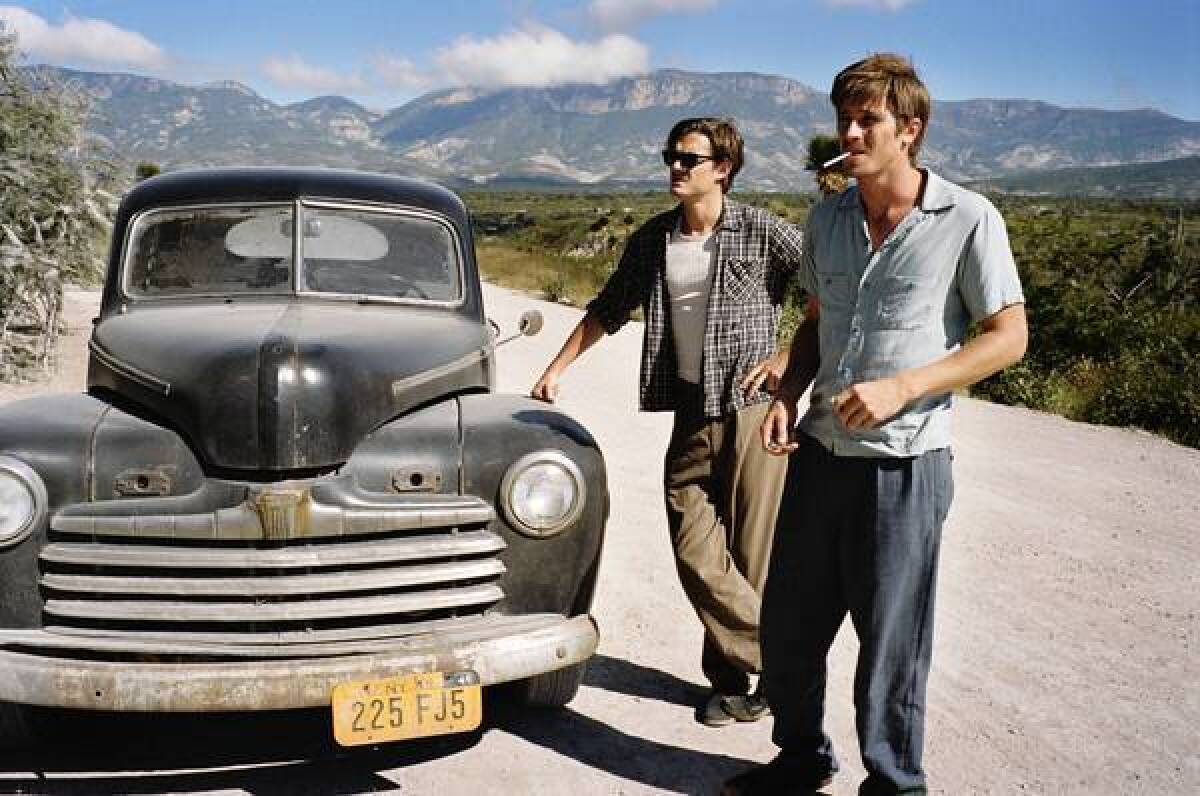

Such questions can’t help but come up in regard to Walter Salles’ long-in-the-works screen adaptation of “On the Road,” which opened last week. The film comes off as a museum piece, cast in amber, a hagiography in every sense of the word. Beautifully shot but oddly lifeless, it is an exercise in nostalgia, which is what the novel stood against.

For me, Kerouac’s peripatetic masterpiece remains powerful precisely because it exists so much in the moment: restless, rootless, even (in some fundamental fashion) shapeless, the road trips it describes compulsive, as if in the sheer act of movement, we might find ourselves most alive.

“So in America,” Kerouac writes in the book’s magnificent closing paragraph, “when the sun goes down and I sit on the old broken-down river pier watching the long, long skies over New Jersey and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast, and all that road going, all the people dreaming in the immensity of it, and in Iowa I know by now the children must be crying in the land where they let the children cry, and tonight the stars will be out, and don’t you know that God is Pooh Bear? the evening star must be drooping and shedding her sparkler dims on the prairie, which is just before the coming of complete night that blesses the earth, darkens all rivers, cups the peaks and folds the final shore in, and nobody, nobody knows what’s going to happen to anybody besides the forlorn rags of growing old, I think of Dean Moriarty, I even think of old Dean Moriarty the father we never found, I think of Dean Moriarty.”

That’s a single sentence, but Kerouac was not an experimentalist. Rather, he was a romantic, so besotted by what he’d been through that it was as if no one had ever felt the way he did.

This, of course, is what writers do; as F. Scott Fitzgerald observed in the 1930s, “We have two or three great moving experiences in our lives — experiences so great and moving that it doesn’t seem at the time that anyone else has been so caught up and pounded and dazzled and astonished and beaten and broken and rescued and illuminated and rewarded and humbled in just that way ever before.” With Kerouac, however (like Fitzgerald), those experiences have become so iconic that they are no longer completely his.

Even when I first read “On the Road,” as a teenager in the 1970s, the core of its action — driving, talking, smoking dope, listening to music — was what my friends and I did every day. It took me years to understand what the book was getting at, which is the bittersweet ephemerality of everything, the idea that to “know time” is to know ourselves as at time’s mercy, which makes its frantic movement less exuberant than desperate.

That is Kerouac’s message, the message at the heart of all his fiction, made explicit by the ancient hitchhiker who, late in the novel tells Sal to “Go moan for man.” Tellingly, this idea is absent from the movie, which is about not desolation but a kind of studied cool instead.

To be fair, such a pose has its roots with Kerouac also — or more accurately, with Cassady. This is one of the most common misreadings of “On the Road,” that, in the words of Kerouac’s friend, the novelist John Clellon Holmes, “[People] kept mixing Jack up with Dean Moriarty, they kept thinking he was like Dean Moriarty — in other words, Neal Cassady — and he wasn’t.”

No, Kerouac was the hanger-on, the chronicler, writing it all down as a way of reckoning with his vulnerability. All these years later, this is what lingers about the novel, its air of universal longing, of a human being adrift in a universe that he doesn’t, that he will never, understand.

I didn’t get this as a teenager. It was only when I reread the novel in my late 20s (Sal and Dean’s age) that I began to recognize what Kerouac had in mind. Twenty years later, I read the book again on its 50th anniversary and saw it through yet one more filter — let’s call it the filter of the other side. By then, I was nearly old enough to have been Sal and Dean’s father, as old as Kerouac and Cassady had been when they died.

The myth about “On the Road” is that it is a book about, and for, young people, which the film, with its hipster diffidence, perpetuates. But youth and time, as Kerouac understood, are very different things.

No, the truth of the novel is more complicated, for, like all great books, it changes on us every time we read it, depending on who and where we are. The first time I encountered it, as a kid, I was disappointed; the second, as an adult, I identified. But it was this most recent reading that revealed the book to me: a desperate yawp in the face of mortality, “like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.