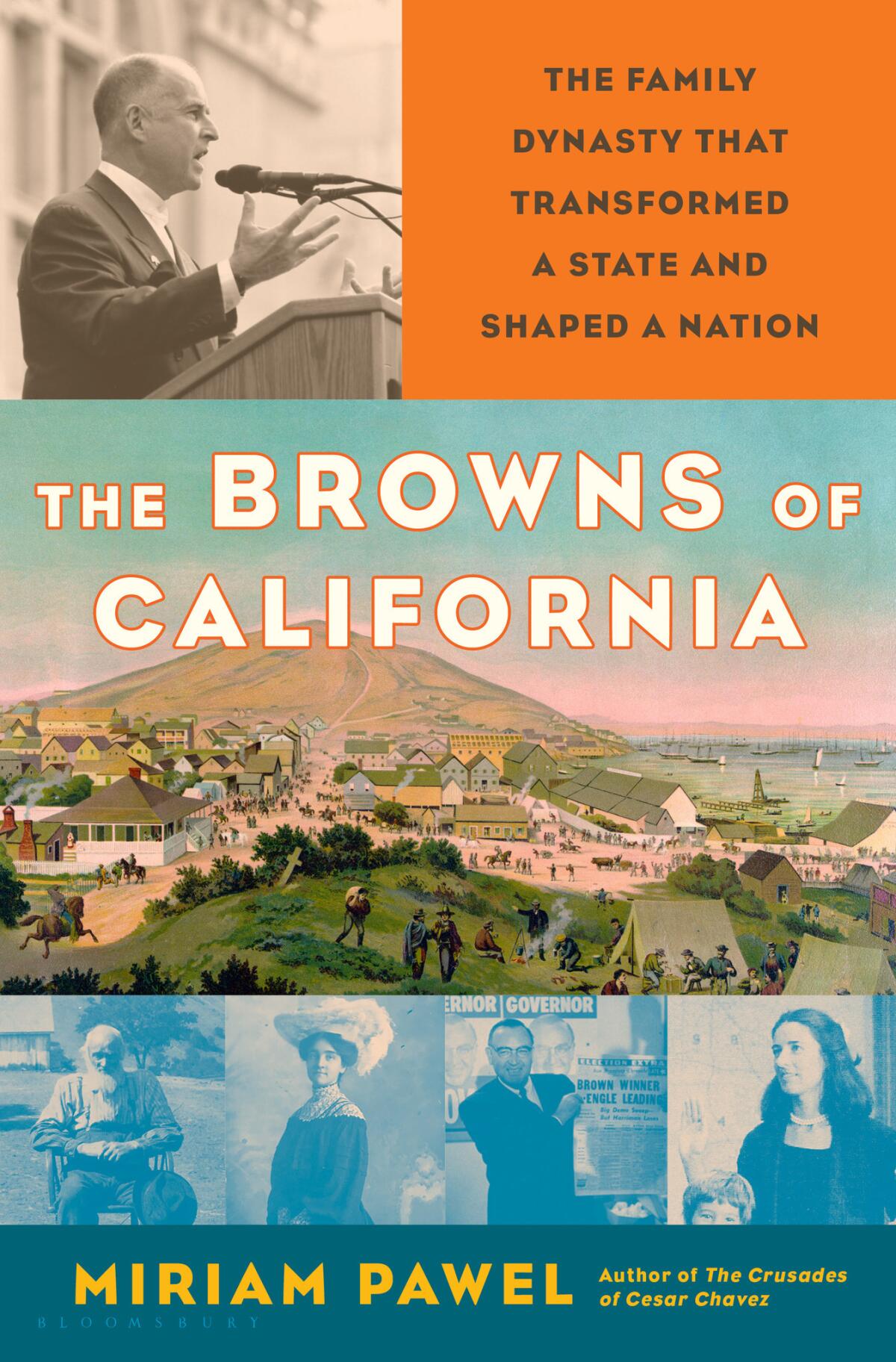

In ‘The Browns of California,’ Miriam Pawel shows how Pat and Jerry Brown shaped a state and a nation

- Share via

A man from Germany settles in rural California. Nearly an adult, his daughter seeks more in San Francisco, where her son eventually mounts a successful campaign to defeat Richard Nixon. He’ll later telephone the disgraced president, offering condolences. With no love for the impeached, the governor’s son replaces his dad in Sacramento, and soon, everyone hears how the new man in town consorts with rock stars and visits secret societies and insists space is the future. There’s a difficult nickname, a run for president and two more. His sister rises to State Treasurer but misses her own bid for governor.

Government can feel too big for any one man, woman or family to have made a real difference. But in an elegantly structured and engrossing new book, “The Browns of California,” longtime California writer Miriam Pawel argues it’s one family in particular that has helped California become not just an exceptional hunk of land on the edge of an ocean but an ever-updating blueprint for all the ways America can be better.

In the spring of 1848, San Francisco consisted of just 575 men, 177 women and 60 children. Fattened shortly thereafter by residents seeking gold, the city grew to 25,000 within a year. “[U]nburdened by tradition, open to experimentation,” Pawel writes, these new Californians “devised routines, invented machines and established lifestyles that suited their needs. They could not wait for supplies and knowledge to migrate from the east.”

Last child of August Schuckman, Ida fell in love with turn-of-the-century Bay Area, marrying an Irish Catholic and giving birth to a son they named Edmund G. Brown. In 1917, he acquired the nickname Pat, when in a speech to sell war bonds the seventh grader quoted from Patrick Henry’s famous line, “Give me liberty or give me death.” Originally a Republican, Pat found inspiration in President Roosevelt’s ethic of service and the promise of a more benevolent government. It was, in fact, while standing at a urinal beside his best friend, Mathew Tobriner, that the young lawyer officially resolved to become a Democrat — a detail Tobriner “delighted in recalling,” writes Pawel.

The state was changing as well. During World War II, military and aerospace dollars arrived; Pawel reports that in the year 1940, total federal spending in California was $728 million, but by 1945, the feds spent as much as $8.5 billion. Operating more like cities than companies, these outfits, such as Lockheed and Douglas, begin to offer daycare, healthcare, banking, meals and entertainment. When the war was finally over, nearly a million veterans stayed in California — in part to embrace the idea that benevolent services could help make life better.

Energized by a growing sense of the possibility of justice and the power of government to ensure it, Pat pivoted from law to politics, becoming attorney general and then dreaming bigger. He loved to talk: The two-hour trip from San Francisco to Sacramento, Pawel writes, could take him all day, because he stopped to chat “at every restaurant or bar along the way.”

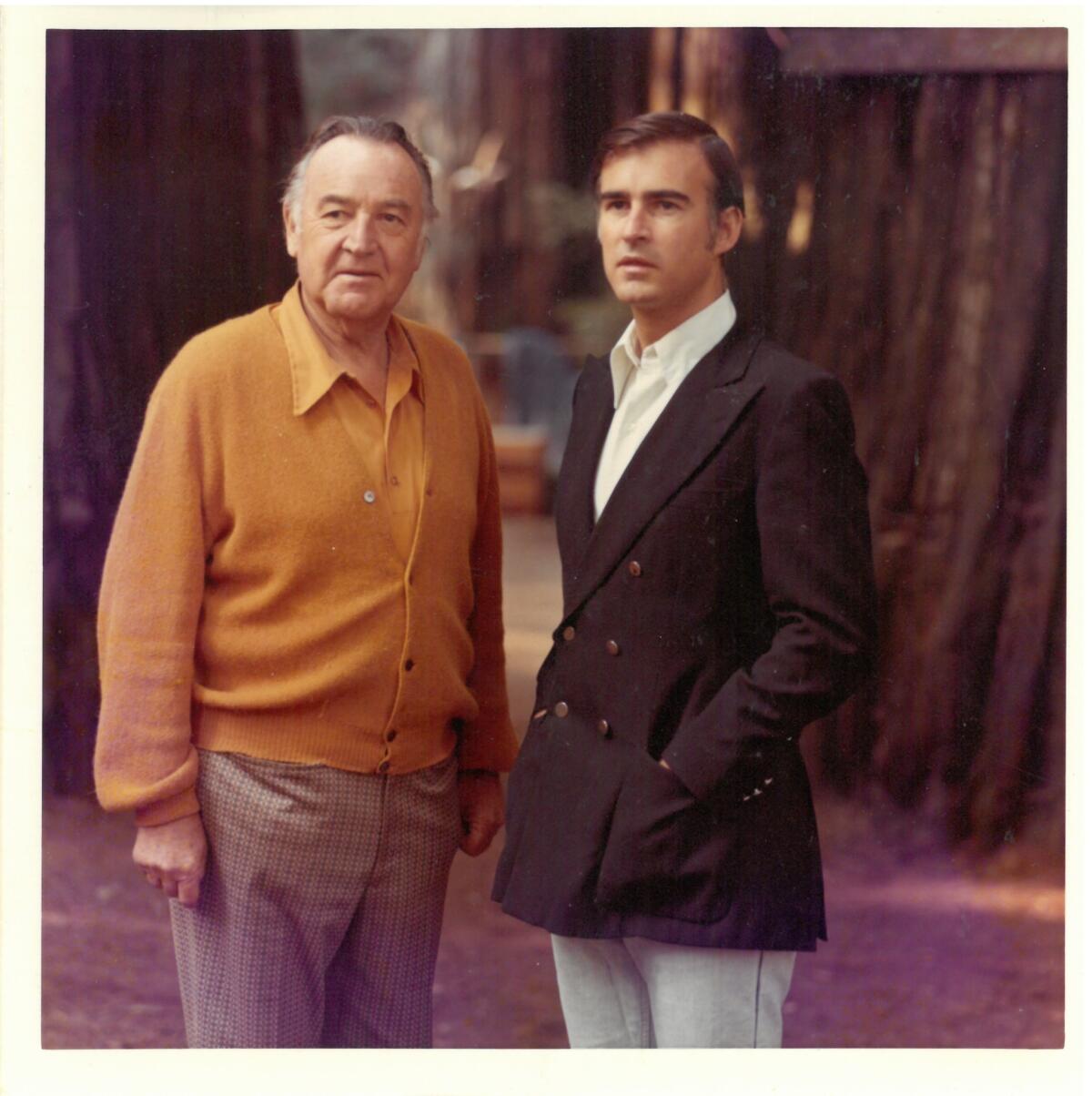

Meanwhile, his precocious son — in high school, he pestered friends, talking all night about “the difference between Kant and Greek philosophers, or the failure of democracies or the reasons people didn’t vote” —joined his friend Frank Damrell in fishing out all the money from their pockets and tossing it out the car window. The year was 1956, and they were joining a Jesuit seminary. “The material world,” Jerry said later, “didn't interest me as much as a life of quiet contemplation.” While the son studied, the father governed a state that had grown to 15 million. Every night, Pawel reports, the governor tried to imagine the constituent who needed his help the most, and then he prayed for that individual, whom he called “the most forgotten soul in California.”

In addition to the state’s frontier spirit (and the family’s faith) another major factor in the Browns’ ability to chart a pattern-breaking course for the Golden State was the growth in California of a whole new kind of American populace. In the 1950s, the equivalent of one high school opened a week. Newcomers poured in from all over the country, and also the world. As governor, one of Pat’s lasting achievements was a new master plan for the state’s public education, which established the California State University system and emphasized free tuition at all public universities — the latter of which Ronald Reagan and subsequent governors (including Jerry) slowly unraveled. “Only in California,” Pat said, “can a young man or woman who has ability go from kindergarten through graduate school without paying one cent in tuition.” To stay on top of his enormous portfolio, Pat carried at least two briefcases, “so overstuffed with books and documents that they never closed.”

Growth also brought smog and traffic and even the paving of some of Pat’s beloved Yosemite. Yet it was generational discord that stumped Pat most, especially when a protest movement arrived at his favorite place: Berkeley. Jerry wasn’t particularly sympathetic either. Said his father: “This is not a matter of freedom of speech. We must have — and will continue to have — law and order on our campuses.” (One place the pair did diverge was the elder’s continued support of the war in Vietnam.)

In the spirit of a changing California, the savvy Browns pivoted to Los Angeles. “People in the Bay Area,” Pawel writes, “might regard Southern California with disdain as a cultural wasteland, but people in Los Angeles didn’t much care.” In 1966, the city went from one state senator to fourteen. The eight counties of southern California controlled more legislative seats than the other fifty combined. More than half of the state’s voters lived in the L.A. TV market.

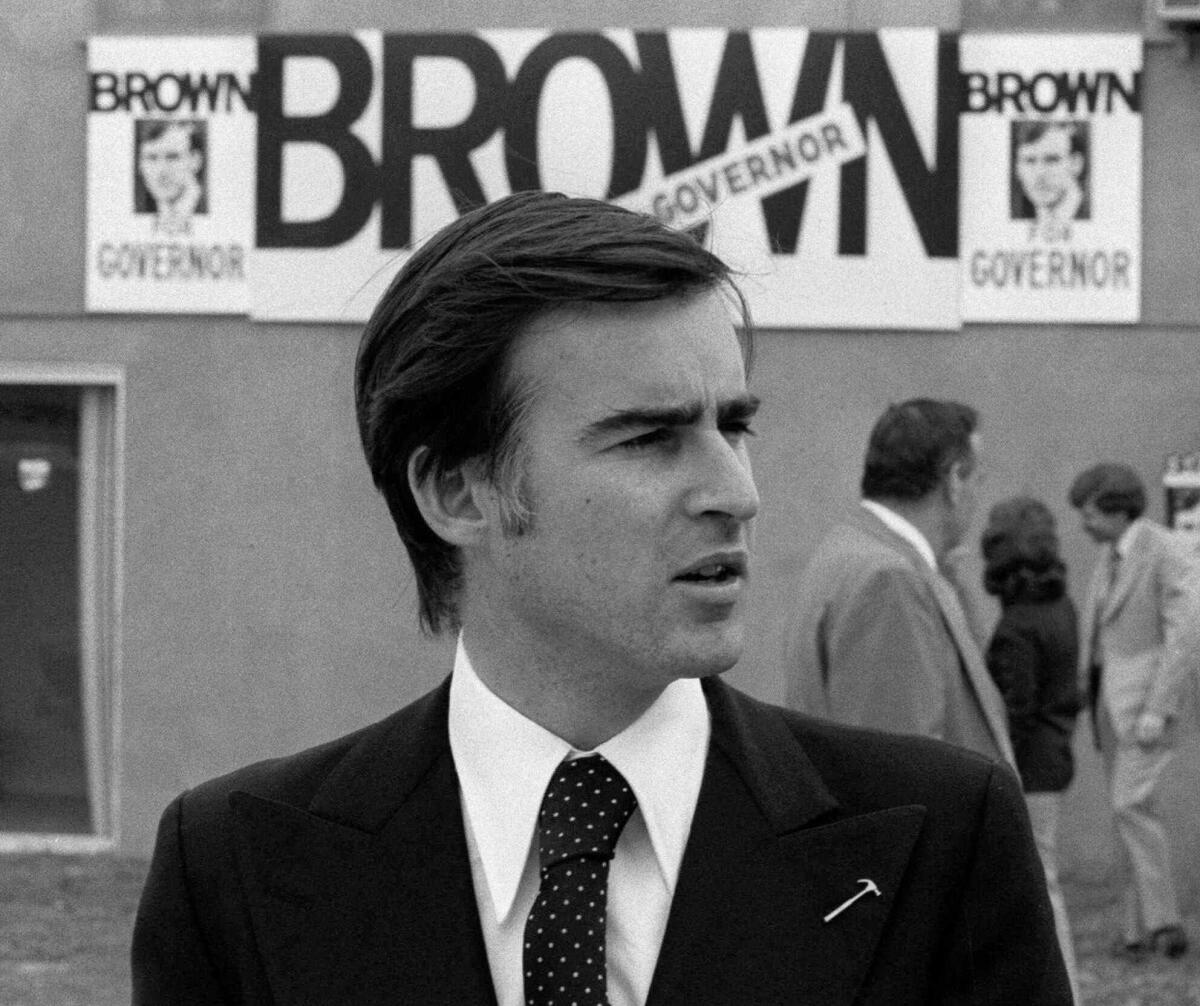

If Pawel’s portrait of Pat is a bit sepia-toned, the book gains speed when the author focuses on a maturing Jerry. The promising son started in L.A. at a boutique law firm, arriving late, struggling into his jacket, tie flying, rolling through town in an old white Chevy Malibu that Pat gave him when he failed to pass the bar. In his first elected post, Jerry gained notoriety for frugality, chastising fellow school board members for spending $700 each on office furniture. Gearing up to run for secretary of state, he told his campaign manager it wouldn’t be like his father’s race. “He did not hug people or kiss babies,” Pawel writes. “He rarely smiled.” If his father’s style was “low-comedy,” Jerry preferred phrases in Latin and historical references.

Sworn in as governor in 1975, Jerry became as well-known for being open to new ideas — going so far as to hire random strangers, if they interested him — as he was in ignoring or being late to meetings, keeping key stakeholders waiting and eschewing most of the niceties of a typical governor. “Pat Brown had worked hard to accomplish things within the system,” Pawel writes. “Jerry came to blow the system up.”

The young governor dated Linda Ronstadt. He had a cool house in Laurel Canyon. He battled a statewide vote to slash taxes and then embraced austerity as something interesting and worth honoring. Journalists ate it up, including writers from Rolling Stone and Playboy, crews from 60 Minutes and newspapers from Korea and Japan. Even City Lights, the seminal San Francisco bookstore, rode the wave by publishing “Thoughts,” a slender book of the governor’s quotes. Asked to give a commencement address, Jerry declined to wear academic robes and changed immediately after the speech into jeans and a denim shirt, flying to Northern California to visit a Maidu Indian ceremonial site.

Even if the reality of Jerry’s early statecraft involved a lot of what could feel like impulsive idea-chasing and a growing sympathy for anti-government conservatism, there was a third main factor that would insure he and the family be remembered as trailblazers. This was the state’s powerfully alluring but ultimately fragile ecosystem.

From its inception, to be a Californian, Pawel writes, was to have a relationship with its beautiful features; residents camped and hiked and explored. But large-scale farming required tremendous amounts of water, and during his tenure the elder Brown broke tremendous ground in establishing procedures and facilities to transport the precious resource around the state. Then, in 1969, an oil spill in Santa Barbara left beaches covered in tar. In response, in one of his own greatest acts as governor, Jerry created a permanent Coastal Commission, with “power to review new projects and protect public access to the seashore.”

Flipping through the chapters, the book can take on the feel of a Forrest Gump romp: But in truth, from the Gold Rush to Apple Computers to the great trauma of Proposition 13, which gutted the tax code, there really was a Brown waving from pretty close to the center of every moment of California’s fascinating history.

After his failed 1992 run for president, when he worked out of the offices of Rolling Stone and stayed with the writers Joan Didion and John Dunne, Jerry disappeared for a while. It was his sister Kathleen who kept the family’s name on the ballot, running successfully in 1990 for California State Treasurer — a uniquely powerful post — and then losing the 1994 governor’s race to Pete Wilson.

In a period that might have seen his fame fading, Jerry spent some of the 1990s hosting a radio show, where he interviewed Gore Vidal about the Kennedys — Vidal said that other American dynasty “never got beyond the pleasures of winning. They were blank.” In 1999, Jerry ran for office again, becoming mayor of a pre-gentrification Oakland. (Imagine Ted Kennedy doing that.) Seeking to help redevelop its downtown, the former governor found himself fighting to undo laws he himself had made 20 years earlier.

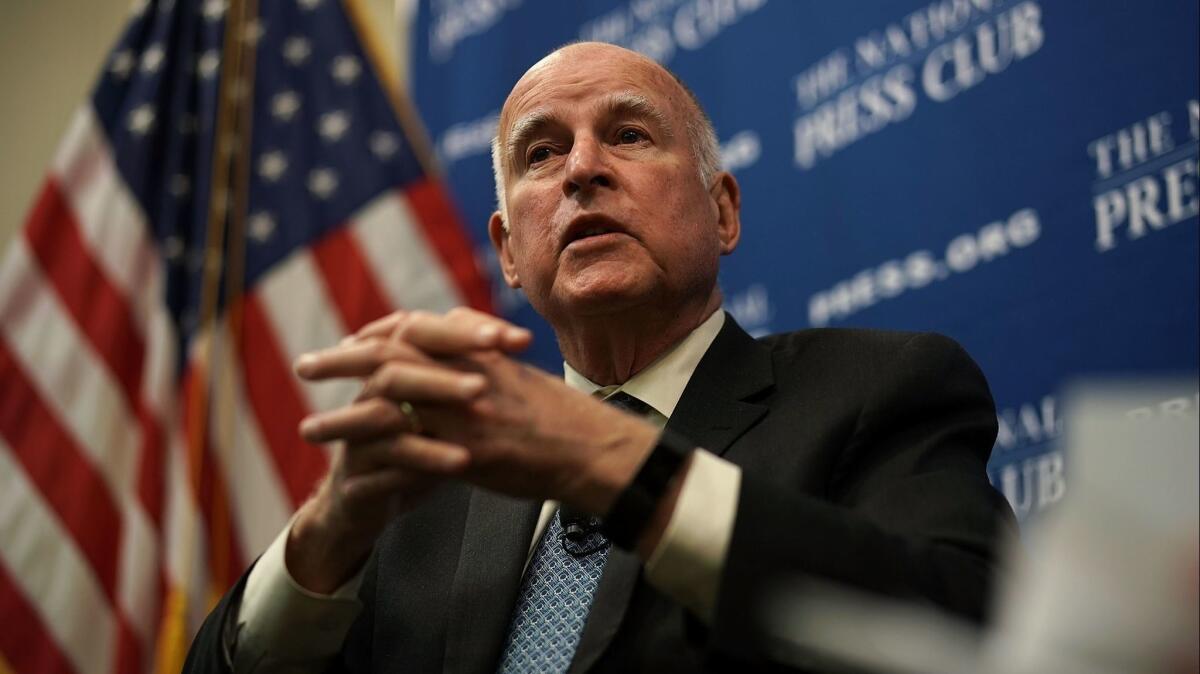

Perhaps the journalist Carey McWilliams might have been correct, suggesting that Jerry Brown “could only have emerged to national prominence in California.” In any case, it’s a legacy that’s still building, with a second act that began in 2007, when he became attorney general, followed by reelection to governor in 2010 and 2014.

Pawel's book slows a bit at the end, perhaps cowed by the difficulty of wrestling with a subject who is still alive and various decisions still being made — such as fate of the cross-state bullet train. And though the long reign of elected Browns will apparently end with the swearing in of a new governor this January — and neither he nor his father (or sister) were or ever will become president — the books argues persuasively that the decisions they’ve made, without question, will continue to ripple outward for years to come.

Indeed the final fifth of this wonderful and essential book highlights what might be the most important — and most broadly relevant factor — that makes the Brown family and its home state of California so key to understanding where America is, and where it might be headed. For decades, like much of the rest of the nation, California had been ruled by a white majority. More recently, however, the electorate, Pawel writes, was finally “beginning to match more closely the people who depended on public schools, colleges, health care and social services.”

If the Kennedys have Martha’s Vineyard, the Browns claim a dusty town called Calusa. The uniquely California nature of their dynasty doesn’t make the family’s belief in the power of government any less inspiring. In fact, it was maybe in one number that Jerry and Pat and Kathleen’s priorities spoke loudest — and most powerfully about what kind of America we can and should become: In the fall of 2017, an average of 45% of freshmen at the nine UC campuses belonged to the first generation in their families to attend college.

Nathan Deuel is the author of the memoir “Friday Was the Bomb: Five Years in the Middle East.” He is a lecturer in the Writing Programs at UCLA.

::

Miriam Pawel

Bloomsbury: 496 pp., $35

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.