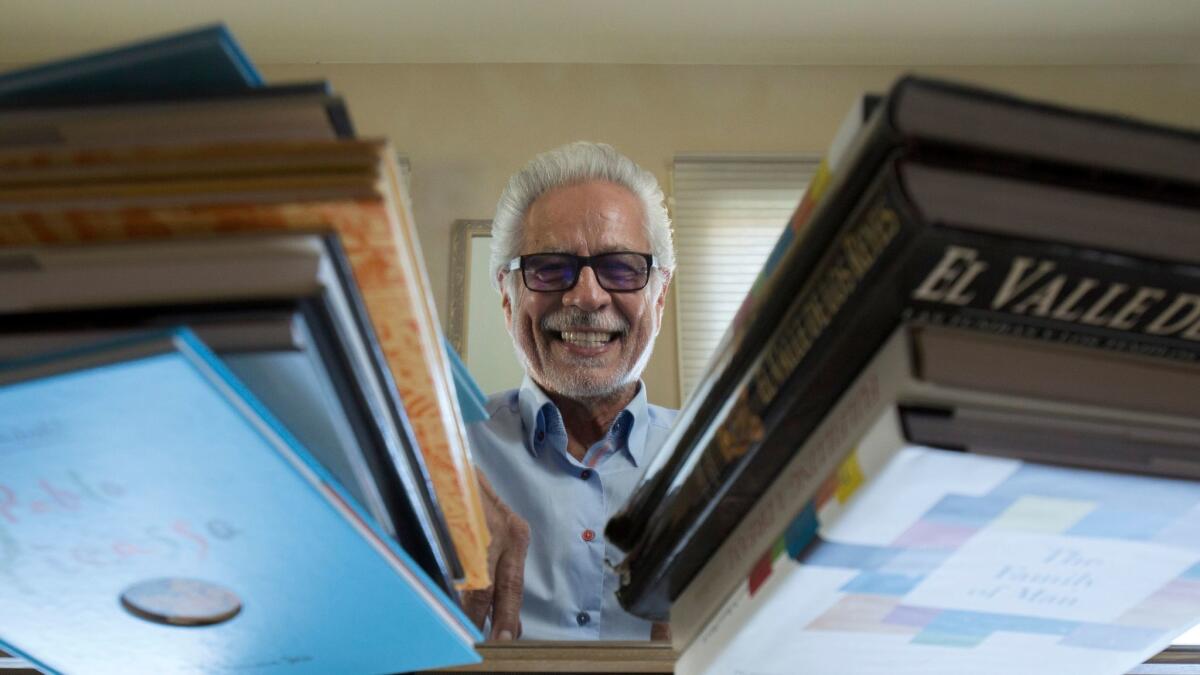

Rueben Martinez, winner of the Innovator’s Award at the L.A. Times Book Prizes

Reuben Martinez, whose barbershop became Libreria Martinez Books and Art Gallery, has received the L.A. Times Festival of Books 2016 Innovator award.

- Share via

“These were my tickets out of the copper mines,” says Rueben Martinez, sweeping his hand over the books stacked on the coffee table inside his small, sage-colored home. A sign on the lawn announces, “This House is Celebrating its Centennial,” and shaded by two stately pepper trees, the craftsman could be a child’s drawing of the platonic home, complete with a pair of porch recliners and a cascade of purple wisteria tumbling from a trellis in the backyard. In the living room, to Martinez’s right, stands a neatly shelved low-boy bookcase containing titles by Mario Vargas Llosa and Miguel de Cervantes, and to his left, a tower of overflow teeters in the corner of the room, but it’s the tan leather barber’s chair, just a few feet away in Martinez’s office, that catches my attention first.

“I had a barbershop the size of these two rooms,” Martinez says, describing the now famous storefront to which he added one unlikely and transformative element: a single bookshelf.

From those humble roots, the barbershop-cum-bookstore Libreria Martinez Books and Art Gallery became one of the largest purveyors of Spanish-language books in the country, as well as a center for literacy advocacy whose influence continues to ripple nationwide. Martinez, who turns 77 on April 16, will be honored with the L.A. Times’ Innovator’s Award at the book prizes on April 21 for his work integrating bookselling, community and activism — his unique ability to weave the galvanizing nature of literature into the fabric of everyday life. “Los libros, to me,” he says of his unprecedented path to a life in letters, “son la fuente y el puente para la sabiduria” — books are the fountain and the bridge to wisdom.

Rueben Martinez will be at the LA Times Festival of Books on April 22nd at 4:30pm, participating in the panel “Listen up, New York: Latino Readers & Writers Have Something to Say.” »

He’s trim and dapper in dark blue jeans and a crisp button-up, his white hair swept back, the rake marks of a comb visibly streaking from his temples. The sense of pride he takes in details, from his cologne and the starch of his shirt to the carefully stressed pace of a story, is evident. “I was 10 years old…It was a hot, hot day in Arizona,” he begins, recalling the Saturday that his stepfather, after spying him reading, sent him to work in the yard, a ruse to burn his book before he could pick it up again. “He threw it in the wooden stove,” says Martinez. “When I opened that up, I could see the spine of book, and I just put it down,” he adds, closing an invisible lid, the memory still real to him. Martinez could not recall with total certainty the book’s title, “because I started to read it, [but] I never finished it,” a loose thread, a piece of unfinished business, which had for a time rankled him. “I don’t call it a regret now,” he says, “because if it wasn’t for that book, I would have never met you.”

By the time he began stocking that single bookshelf with copies of Juan Rulfo’s “El Llano en Llamas,” purchased on trips to Tijuana, Martinez had already transitioned from industrial jobs at Bethlehem Steel and the Ford Motor Co. into a successful barber; well-meaning friends tried to dissuade him from taking what seemed like a discordant leap into books. (He had four children; today, he also has 10 grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren: “My family is my life.”) I asked Martinez why he hadn’t listened. “Because I listened to the love in my heart,” he said, and yet, ever the consummate entrepreneur, he added, “I did do a little bit of research… I would always ask [my customers] when I had them in the barber chair, ‘What do you think of this?’ ‘Well, that would be nice. I don’t know of any other bookstores that are doing that.’ ” Martinez slapped his thigh for emphasis. He had hit upon a demographic, a market and a need: an underserved population of Spanish-speaking readers.

“I used to do it all, I used to do the haircutting, the cleaning up; I used to do the buying and the selling. I worked every day, and I was never tired,” he said, because he felt so electrified by what had become his purpose: “It was a direction in life.” At first, “the barbershop was paying all the expenses,” but “in five years, it started to turn, turn, turn, and in 10 years, the shop was doing so well that I started to slow down on my cutting.”

The memory of his lost, burned book became tinder for Martinez, lending him the tenacity to transform his barbershop bookshelf into a full-fledged bookselling business.

Libreria Martinez attracted internationally renowned authors such as Isabel Allende and Carlos Fuentes, who drew massive crowds, and the store became a haven for cultural events and political discourse. The novelty of a bookstore birthed in a barbershop caught the eye of media, as well as the MacArthur Foundation, which awarded him a “genius” grant in 2004, but it was the byproduct of Martinez’s story that captured — and continues to ignite — the public imagination. In following his curiosity — his passion for reading, his instinct for community advocacy and his inherent business sense — Martinez not only created something heretofore unseen but he also did something even more elusive. He effected real change.

“Back then, bilingual books were a political statement,” said Bobby Byrd, owner and publisher of Cinco Puntos Press in El Paso, “and Rueben understood that immediately.” Martinez frequently bought Byrd’s inventory — “a shot in the arm for a small press,” as he recalls — in particular, Cinco Punto’s bilingual children’s titles. Martinez, he said, “was a gatekeeper, in a way, to kids getting books. And he swung the gate wide open.”

How wide? Nationwide. “I was in Philadelphia once,” said Martinez, “doing a talk, and one of the representatives from Barnes & Noble was there on the panel. He said, ‘Thanks to you we’re carrying books in Spanish.’ ”

Gustavo Arellano, editor of the OC Weekly and author of “Taco USA” and “¡Ask a Mexican!,” saw Martinez’s model “reproduced in many Latino cities in the United States… in Las Vegas, in Sacramento,” in stores that he visited on his book tours. In Orange County, he says, Libreria Martinez “was part of the fabric of the community” and “a space for people who really had none.” Of the man himself, whom after 15 years of friendship, he still calls Mr. Martinez, Arellano simply says, “he is a secular saint.”

Currently, Martinez is a presidential fellow at Chapman University in Orange, the new home of Libreria Martinez, which has been transformed into a community center, and where he serves as a spokesman encouraging Latinos to pursue higher education. Martinez says he doesn’t walk across campus: “I float.” He attended a segregated school, George Washington Elementary, yet nonetheless credits one teacher in particular, Mrs. Brubaker, as a life-long inspiration. She lent Martinez books (including the volume his stepfather tossed in the fire), and they stayed in touch until she died. “I knew Mrs. Brubaker longer than anybody else on Earth,” he said of his former teacher, who recently died, “longer than my parents, my grandparents. She retired and moved up to Lake Isabella, and I would call her three or four times a year…‘Rueben, how are you?’ ” he says in a theatrically quavering voice, as if reading from a children’s story. “ ‘I’m fine, Mrs. Brubaker.’ ‘What are you reading?’ ” She told him she was proud of him, he says, and he feels that his work with youth is a continuation, and a reimagining, of what she taught him.

“This is what I pass on to young people today. That passion, that caring, that giving, that participating, that listening… I tell them, ‘Did you know that almost 56% of Americans only speak one language, and you’ve been speaking two since you were in kindergarten?’ This 21st century that we live in is a century of languages and cultures. I say, ‘Be proud of your parents, be proud of your grandparents, be proud of your first language.’ ”

Martinez was 53 when he opened Libreria Martinez Books and Art Gallery. “People are deciding about retiring at that age,” he says. “I have the opportunity to go on a national level and talk about books in Spanish, and it’s happening in my 70s… I’m never going to retire. It’s too late for me. I’m at the point of no return.”

Indeed, Martinez’s innovations have not ceased: along with one of his daughters, he is a partner in the Hudson Group, North America’s largest airport newsstand retailer. “The opportunity came, let me see, going on 14 years now,” he says. They currently operate 777 bookstores by his count, a number he whips out with startling specificity. That books belong in everyday spaces — the barbershop, the airport — feels like common sense, but Martinez continues to impart his particular flair for doing business with integrity.

“In airports, what we sell is mostly bestsellers. But I recommend to them, ‘We should have books by authors that live in the city. Honor them!’ ” he says, practically leaping up from the couch, his voice suddenly a roar. Throughout our conversation, Martinez often paused to press various titles from his own shelves into my hands, including a copy of National Geographic that he had saved from April 1940 — his birth year. Even now, even in his home, a natural bookseller.

Martinez showed me countless honors — an estimated third of what he’s actually received — displayed in his office. What does it feel like, I ask him, to receive the Innovator Award? “Innovator is a biiiiig word, OK? In – no – va –tor,” he says, parsing out the syllables and sweeping his hand through the air, as if he were reading them in neon lights. “Like you’re building highways,” he says, and I am reminded of his perfect metaphor. “El puente” — the bridge — he called books, but they are bridges to more than just wisdom. In the right hands, books are bridges between generations, between cultures, to one another, to better lives. To meet Martinez is to be reminded of that; he’s someone for whom the astonishing power of books — that they can contain almost everything, the history of man and the futures that we can only imagine for ourselves — has never diminished.

“It was fun,” he says of the Libreria Martinez days, working long and hard and satisfied to create the first barbershop-bookstore this world had ever seen. “I knew I wasn’t going to get rich. Not here,” he says, tapping his pants pocket. “Here, yes,” he says, and draws a circle over his heart.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.