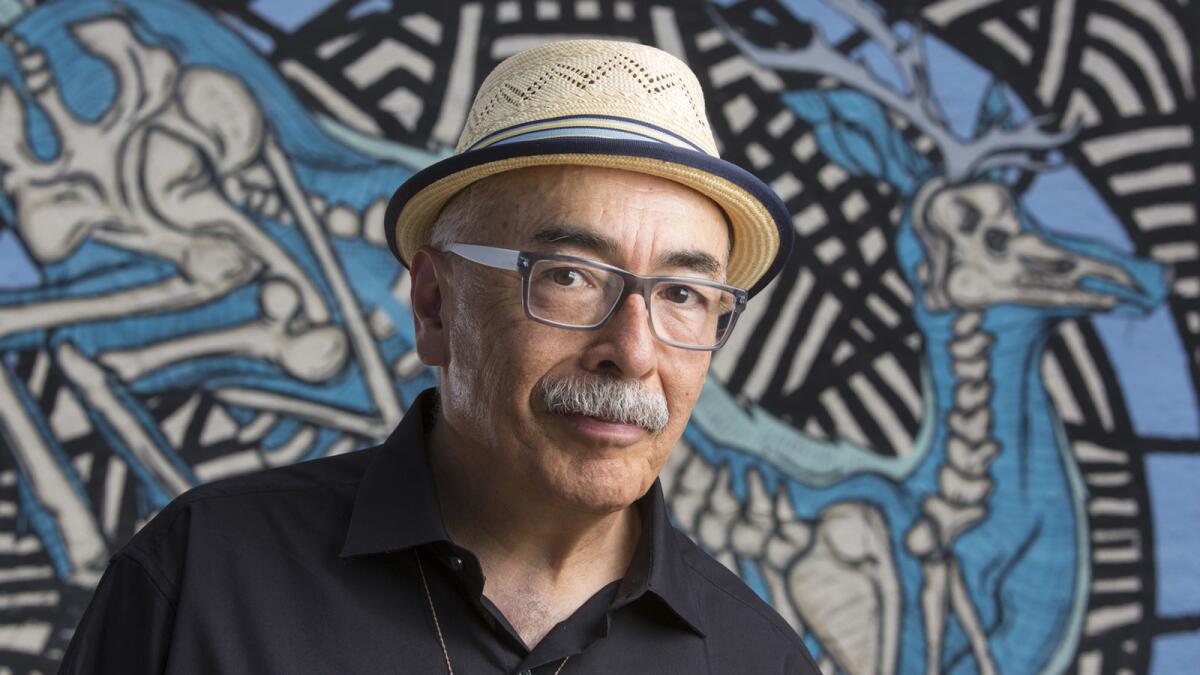

Juan Felipe Herrera new U.S. poet laureate: ‘Shout it from the roof tops’

Juan Felipe Herrera, former poet laureate of California, began his career with poems that often casually combined Spanish and English, uniting the languages of his youth.

- Share via

Walking past a row of books in a library, 21-year-old aspiring poet Juan Felipe Herrera was stopped short by a title: “Snaps.” The book was the debut collection by Victor Hernandez Cruz.

“I opened it up, started reading those poems,” Herrera recalls 45 years later. “Puerto Rican bilingual English style and language and voices. The wordplay, improvisation, it was amazing. That catapulted me. I never forgot it.” In 2012 he found himself sitting with Cruz as chancellors of the Academy of American Poets in New York City.

Now he’s joining an even more prestigious club: On Wednesday, the Library of Congress named him U.S. poet laureate. When he begins his tenure in September, he’ll be the first-ever Chicano poet laureate, writing and speaking in both English and Spanish.

Herrera’s parents, both migrant farm workers, came to California from Mexico in the early part of the 20th century. He traveled up and down the state as a child and attended UCLA with the help of the Educational Opportunity Program for disadvantaged students. Although he got a master’s degree at Stanford in the 1970s in social anthropology, what he really wanted to do was write. In 1988 he went to the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop for a master of fine arts in poetry.

Now 66, Herrera is a master of many forms: long lines, litanies, protest poems, sonnets, plays, books for children and young adults, works that combine verse and other forms. Lately he has turned his gaze outward, with 2013’s collection, “Senegal Taxi,” focusing on Darfur. But his career started closer to home, with poems that often casually combined Spanish and English, uniting the languages of his youth. In “Blood on the Wheel,” he writes:

Blood in the tin, in the coffee bean, in the maquila oración

Blood in the language, in the wise text of the market sausage

Blood in the border web, the penal colony shed, in the bilingual yard …

“He is not consciously ambassadorial,” says Stephen Burt, professor of English at Harvard University. “He doesn’t stop to explain things so people who aren’t Latino will understand them; he just does what he does. And trusts, correctly I think, that the language and the emotional trajectories of the characters or the bits of narratives in the poems will fascinate you enough that if you’re interested and you don’t get the references, then you can go look them up.”

Typically, the U.S. poet laureate does a few official readings and beyond that is free to create his or her own programming during the year. The modest honorarium, $35,000, doesn’t go far, and some poets use the time to write, advise the library on matters of poetry and explore the collections. Others leverage the media to spread the word about poetry; Natasha Trethewey, who served as U.S. poet laureate from 2012 to 2014, partnered with PBS NewsHour on the series “Where Poetry Lives.”

Herrera, who lives with his wife in Fresno, retired from UC Riverside in March, where he taught creative writing for a decade. He recently concluded his two-year term as California’s poet laureate, traveling to hidden corners of the state and showcasing young poets’ work in various media. Along the way he created a massive, multi-contributor unity poem and a number of popular live readings, catching the attention of key players in Washington.

“I think people heard about what he was doing as California poet laureate in ways that you don’t always hear about what state poets laureate do,” says Robert Casper, head of the Poetry and Literature Center at the Library of Congress. “That was really exciting to see.

“He speaks poetry in a way that I think is super-inspiring.... He’s the kind of poet who gives you permission to love poetry, to be excited about it, to be energized by it. To think that it’s something freeing and fun but also relevant to the issues we face, the challenges we have; to understanding the world we’re in.”

Connecting to people through performance is crucial for Herrera. “I used to stand on the corner in San Diego with poems sticking out of my hip pocket, asking people if there was a place where I could read poems,” he recalls. “The audience is half of the poem.”

America has had poets laureate since 1986 (before that, it was called the consultant in poetry). In its nearly 80-year history, the position has been held by such poets as Robert Penn Warren, Robert Lowell, Robert Frost, Elizabeth Bishop, Joseph Brodsky and Rita Dove. Because William Carlos Williams, whose mother was Puerto Rican, never served because of Cold War politics, Herrera will be the first Latino to hold the position.

On Twitter, the reaction to his appointment was overwhelmingly positive. “Gracias, Juan Felipe Herrera,” wrote poet Rigoberto Gonzalez. “You just made so many communities so proud.”

Jessica Ceballos, who runs a readings series in Los Angeles, wrote, “I can’t put into words how genuinely happy/proud I am/feel that Juan Felipe Herrera is our new U.S. Poet Laureate.”

Former U.S. poet laureate Robert Polito, who now heads the Poetry Foundation, tweeted, “Congratulations to Juan Felipe Herrera, our new Poet Laureate! Thrilling appointment. He’ll be fantastic!”

“Wow!” Tweeted Felix Contreras, host of NPR’s AltLatino podcast. “Shout it from the roof tops, my pal Juan Felipe Herrera is named Poet Laureate of the U.S.!!!!”

The appointment is an acknowledgment of the importance of Spanish and bilingual culture in America.

“We’re being recognized in a very powerful and important way,” says Luis J. Rodriguez, author of the memoir “Always Running” and current poet laureate of Los Angeles. “Juan Felipe, poet laureate of the United States — this is symbolic of how important our literature, our stories are.”

MORE FROM BOOKS:

Get ready to be obsessed by these 29 page-turners

23 fiction books you’ll want to read -- and share -- this summer

Listen up: Here are 11 audiobooks you’ll want to ‘read’ this summer

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.